Worker of the Week is a weekly blogpost series which will highlight one of the workers at H.M. Gretna our volunteers have researched for The Miracle Workers Project. This is an exciting project that aims to centralise all of the 30,000 people who worked at Gretna during World War One. If you want to find out more, or if you’d like to get involved in the project, please email laura@devilsporridge.org.uk. This week, volunteer Marilyn tells us all about Nora Morphet.

Nora Morphet was born on 18th April 1898 at Staveley , Nr Kendal , Westmorland to James and Sarah nee Irwin. James was the son of an agricultural labourer ( 1871 census) and at 17 in 1881 James is a Railway Porter. James and Sarah were married in Brampton in 1891 according to Marriage registers. They lived in and they lived at 15, Dalston St, Carlisle

The 1901 census places the family at Railway Cottage, Staveley, James being a Railway Signalman age 35 and born at nearby Barbon, Westmoreland. Sarah was born in Brampton, Cumberland , now aged 36. They already had 4 children – Mary Alice , 8 and Ethel, 3 born in Brampton , Nora 2 and James 1 born in Staveley. A 5th child , Esther Annie was born on 2nd July 1901 but tragically Sarah the mother died on 13th December according to the Register of deaths. The parent’s ages indicated in the 1901 census are questionable when tallied with other sources of evidence.

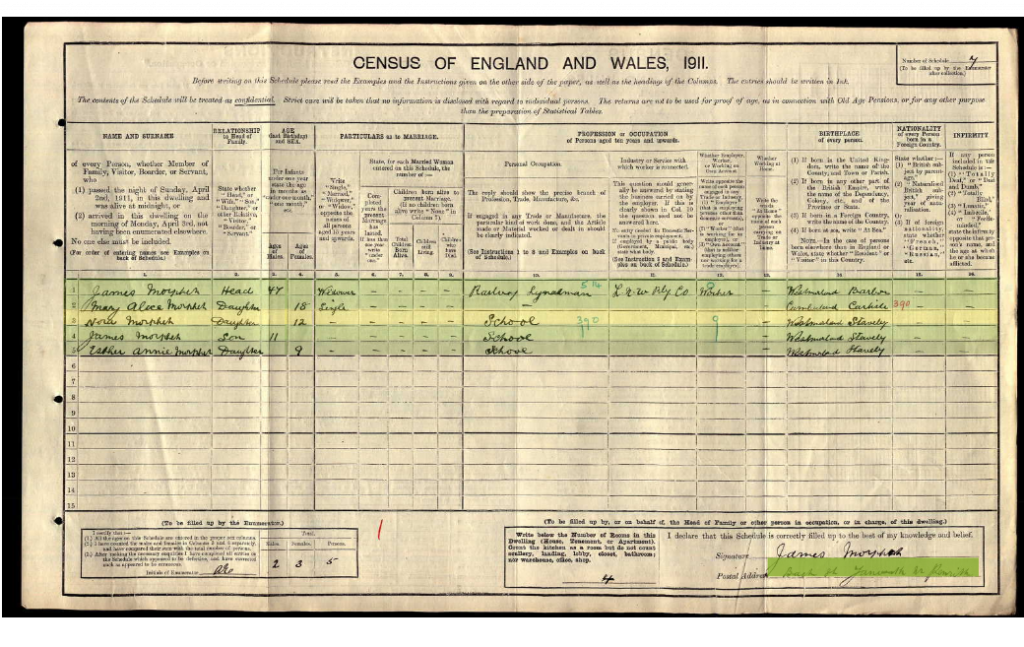

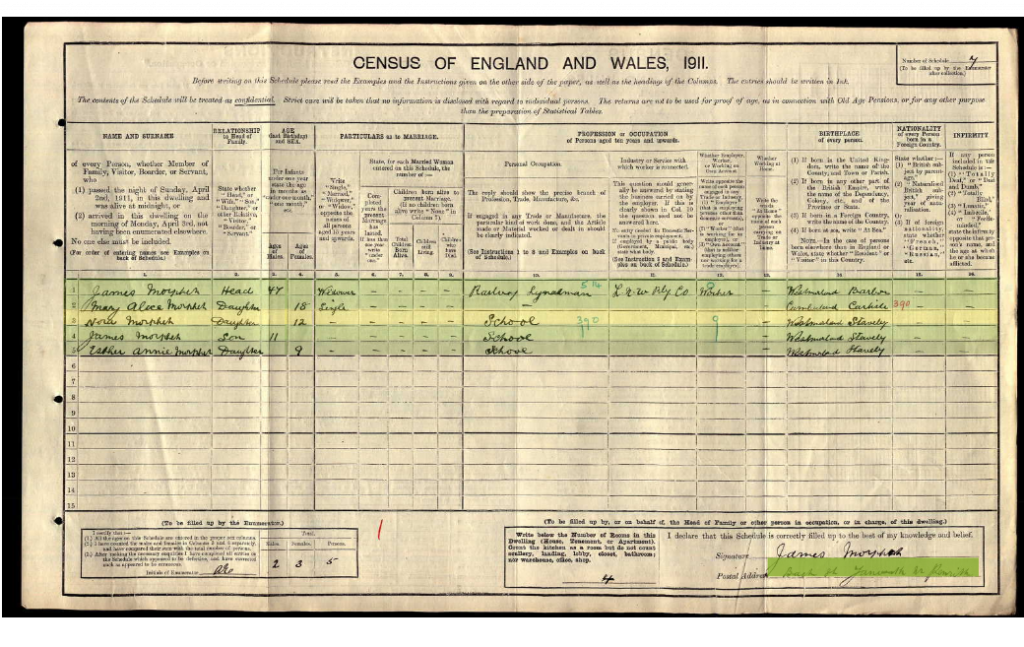

By 1911 , James now a widower for almost 10 years, lived in Back Street , Yanwath ,near Penrith with his young family. He is now 47, still a Railway Signalman. Mary Alice , 18 , described as single and now indicated as being born in Carlisle which links with other sources – the young couple had lived at 15 Dalston St when they first married. Nora, 12, James 11 and Esther 9 all scholars.

Ethel is to be found on a separate census return as a 15 year old servant for a miller and his wife at Morland ,Penrith.

Ethel is to be found on a separate census return as a 15 year old servant for a miller and his wife at Morland ,Penrith.

The Cumberland and Westmoreland Herald- Saturday 30th December 1911 report in full the Christmas performance by the whole village school at Yanwath. Nora , James and Esther all performed. Nora played the part of a Christmas fairy.

Here we turn to the plight of James junior. The Forces war record tells us that in July 1915, James , a private in the Coldstream Guards having previously been reported missing was now being reported by the German Authorities as being in a POW camp. Having been born in 1899 he clearly lied about his age in order to join up. One can only imagine what Nora and the rest of the family suffered at this time.

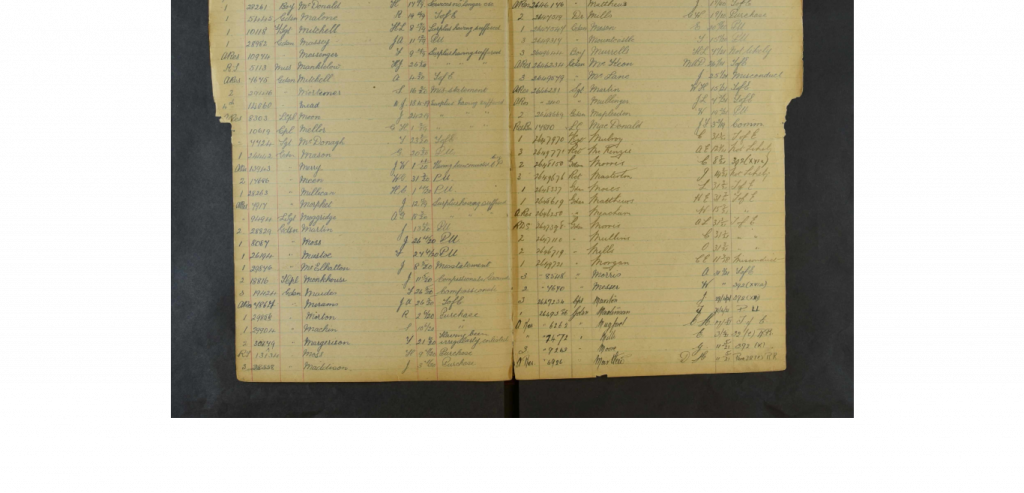

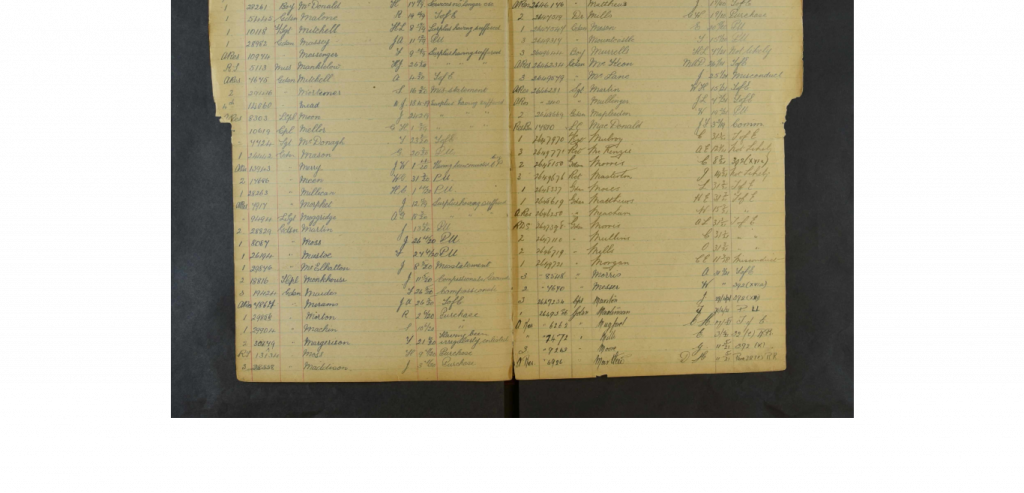

Coldstream Guards Log for James Morphet

The Coldstream Guard log tells us that he was dismissed on 12/11/1919 “ Surplus having suffered. “

He must have joined the Royal Irish Constabulary rather than go back home to Carlisle where the family were now living at 6 Millholme Avenue. The Royal Irish Constabulary pension ledger clearly shows James as being pensioned off in February 1922 ( now aged 22/3) , £46.16.7d to be paid annually and all correspondence to be sent to 6 Millholme Avenue, Carlisle. He was clearly going back to live with his father.

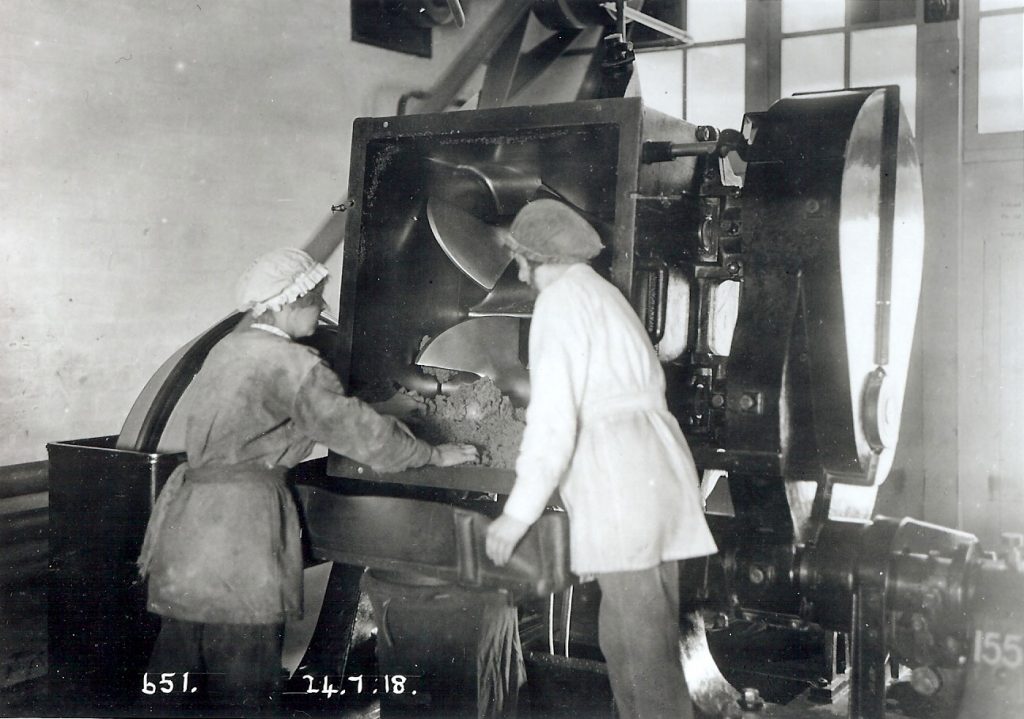

Meanwhile, Nora we can assume responded to a call to work at HM Factory Gretna in 1916 and more than likely travelled on a daily basis from Carlisle. Throughout her whole time at Gretna she must have worked with the knowledge that her younger brother was a prisoner , that he had joined up when he was too young and that he may not come home again.

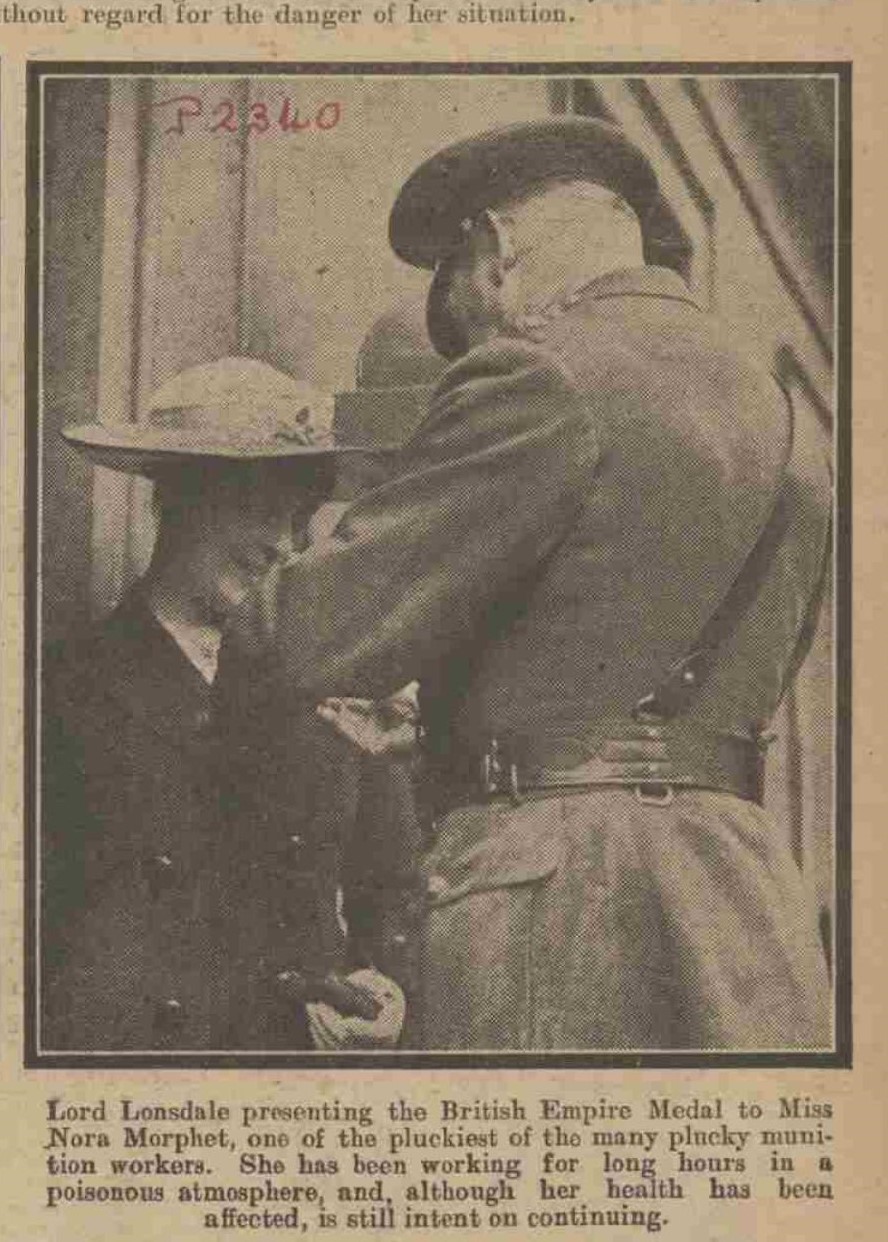

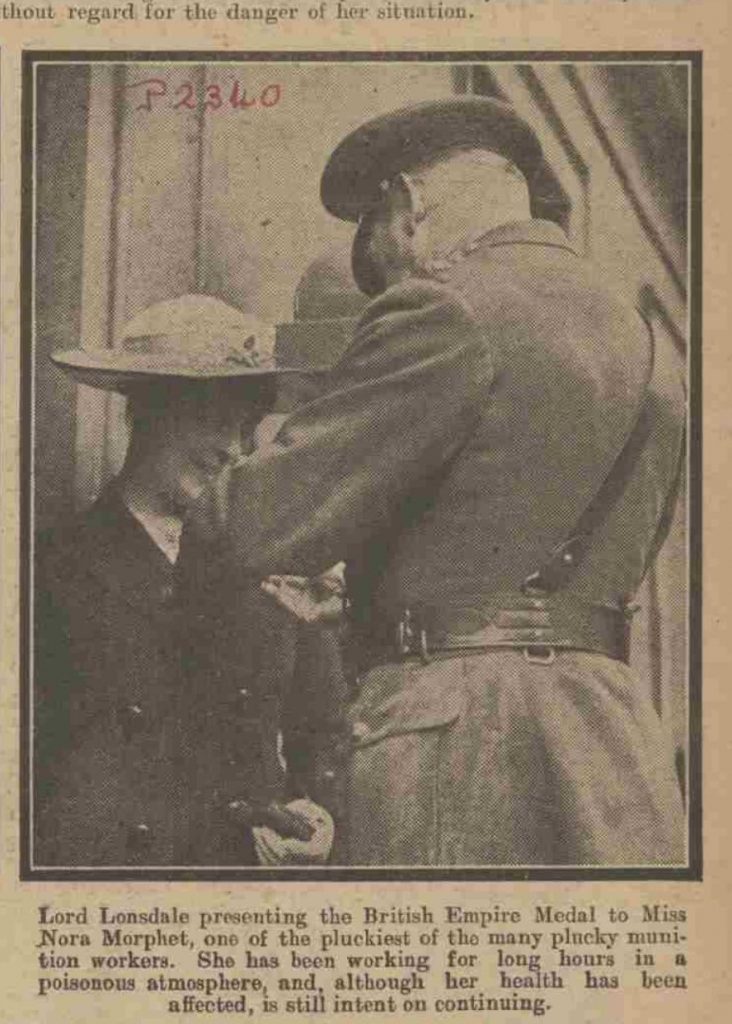

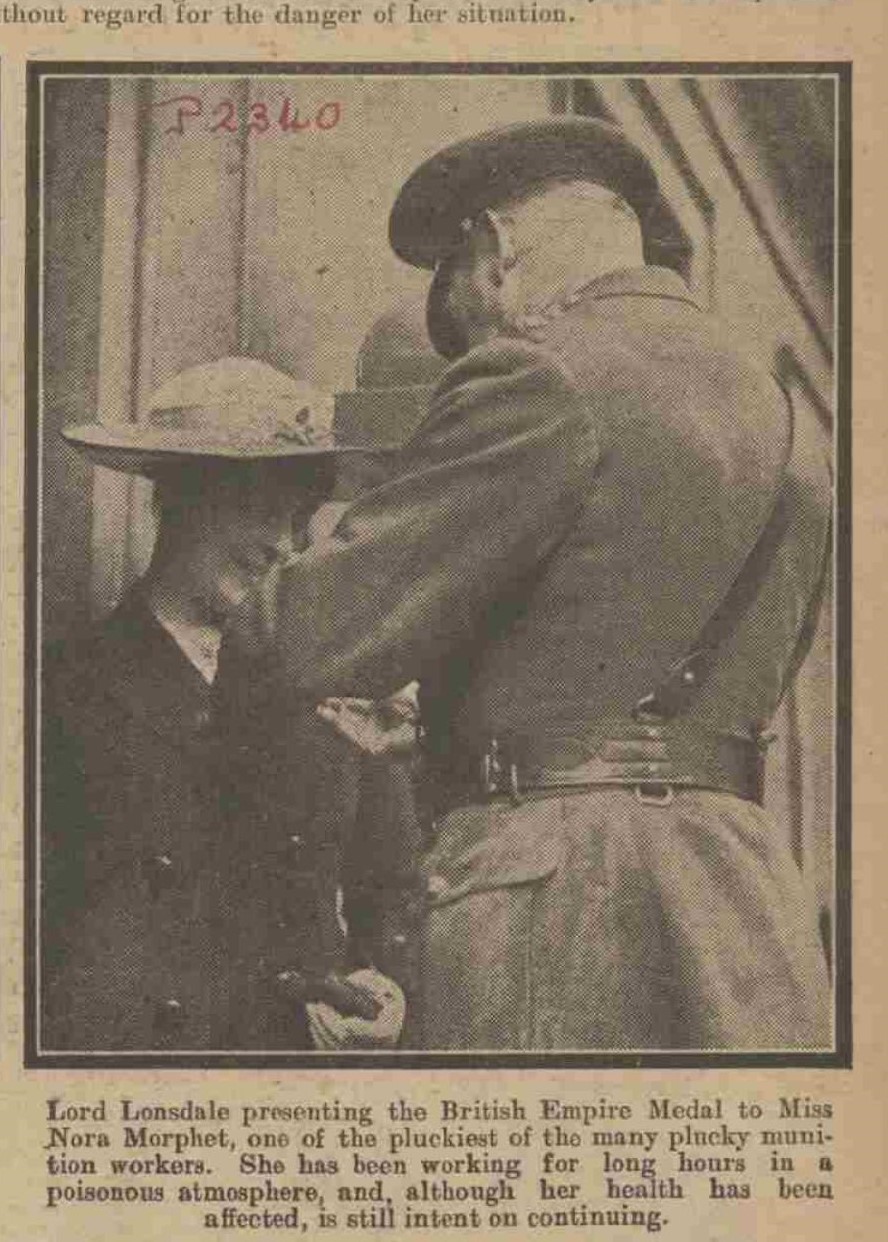

Nora must have worked as a munitionette at Gretna because the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer of Thursday 2nd May 1918 reported “. Miss Nora Morphet, 6, Millholme Avenue, Carlisle, for courage and high example in continuously working long hours in poisonous atmosphere which habitually affected her health;”

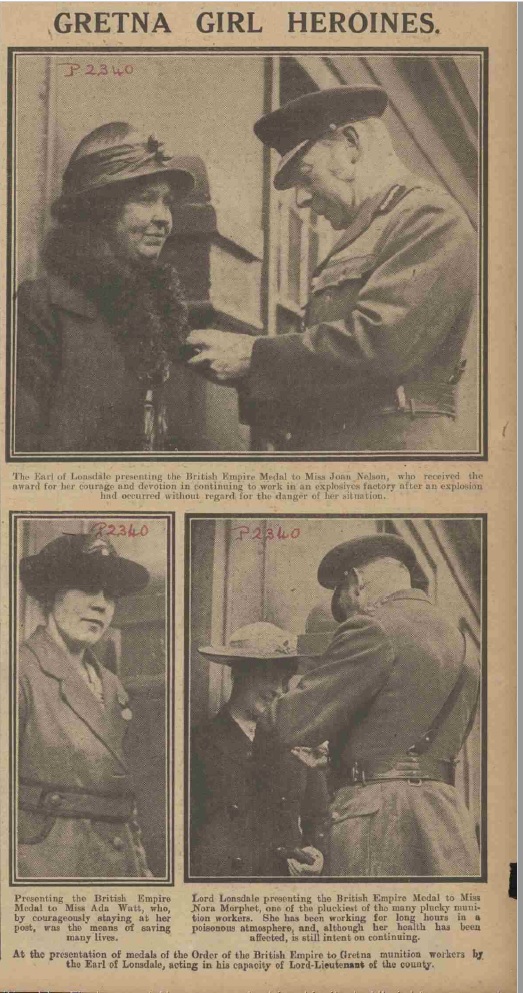

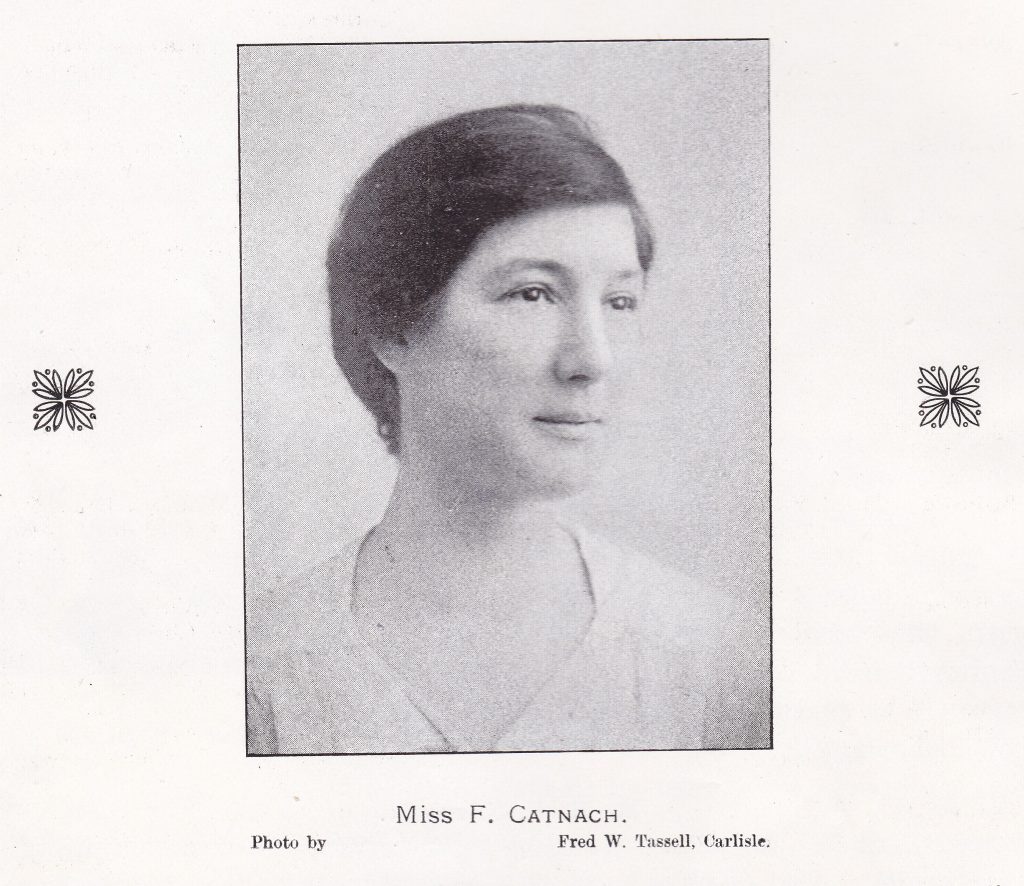

Nora pictured in The Daily Mirror, May 3rd 1918

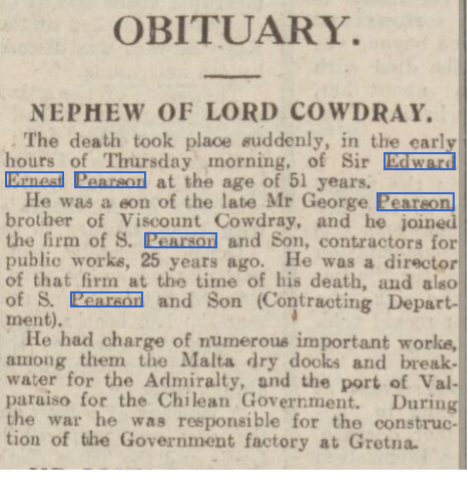

For this she was one of 3 young women Presented with British Empire Medal by Lord Lonsdale in Carlisle “MEDALS FOR BRAVE CARLISLE WOMEN WORKERS. By command of the King, Lord Lonsdale, the Lieutenant Cumberland, at the Town Hall.”

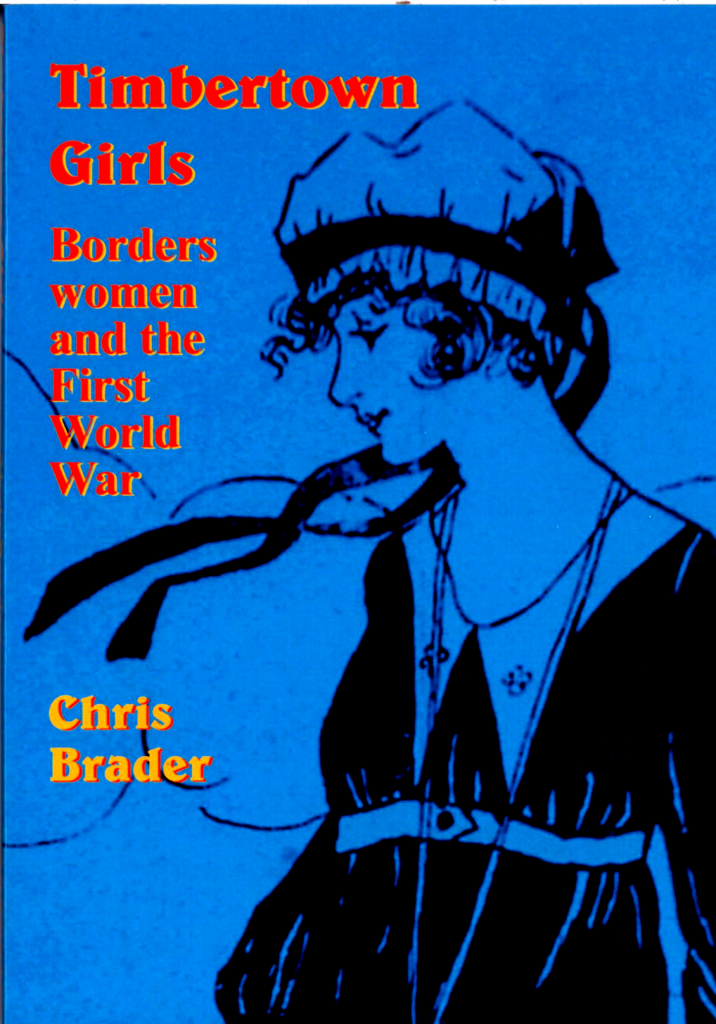

Chris Brader in Timbertown Girls refers to the three girls but there are no specifics of why exactly they had been awarded over and above many others and what particular effect it had on their health.

Not only was this reported but it was photographed and Nora appeared proudly on the front page of the Daily Mirror , Friday 3rd May 1918.

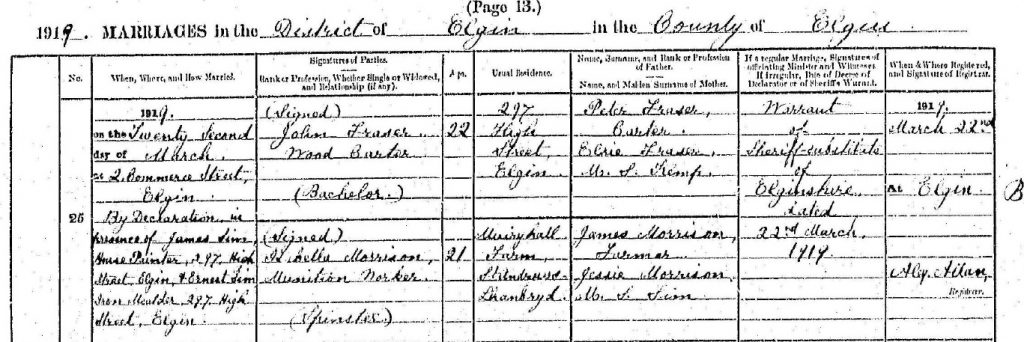

We lose track of Nora at this point until April 1926 when she is listed in the Marriage registers for St Pancras, London as marrying an M H Lyons. Was she in service in London? How had their paths crossed?

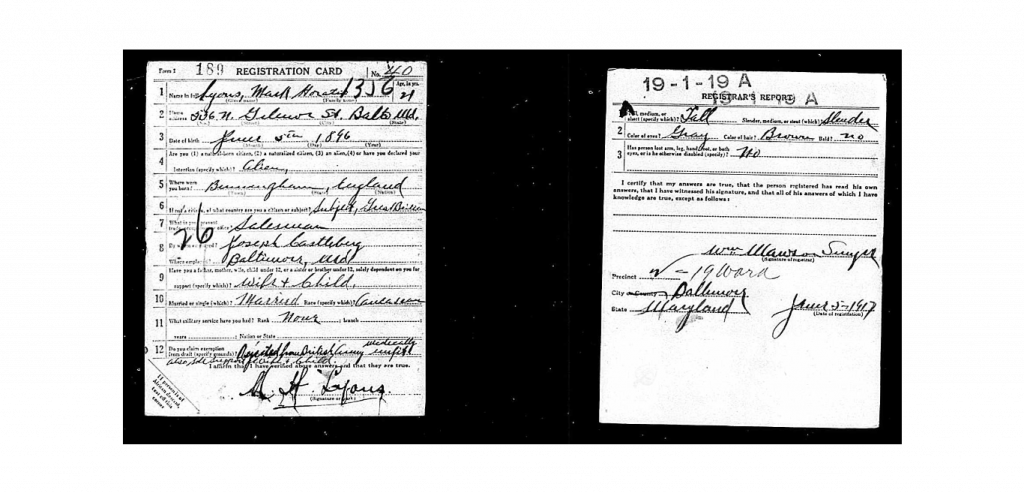

Mark Horatio Lyons , a young widower, described variously as Diamond dealer/salesman/jeweller in Passenger lists for trans Atlantic crossings. He was from Edgbaston , King’s Norton, Birmingham. Passenger lists show his as travelling to New York via Ellis Island on 6th January 1916 aged 19 on board the SS Paul, with the intention of becoming a permanent citizen. On the same passage is a Florrie Hazel Myra Price, his future bride, also of Edgbaston.

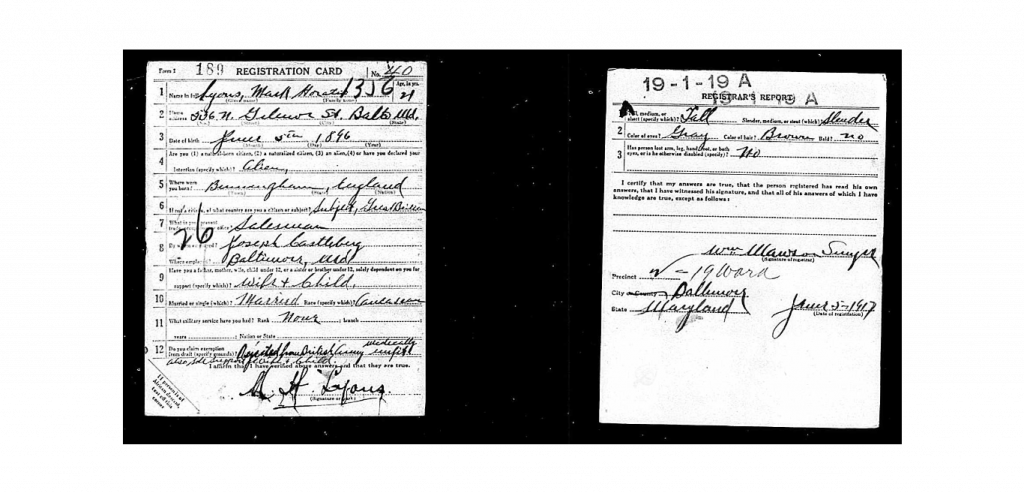

A US Army draft card appears in the records for Mark H Lyons, born in Birmingham , England and stating that he had been deemed “ medically unfit for the British Army and he is the sole supporter of his wife and child” Subsequent events date this at autumn 1918. He is described as tall, slender with brown hair and blue eyes. We can assume that he married Florrie in Baltimore, Maryland and they had a daughter.

Mark Lyon’s (Nora’s first husband) US Army Draft Card

On April 12th 1919 he arrives in Liverpool aboard the “Aquitania” , described as single and a diamond dealer . Florrie had died in February in Baltimore , Maryland and findagrave.com shows that both Florrie and the baby daughter were interred at the Price family grave in Brackenwood Cemetery Birmingham on 17th April 1919. Florrie had died before they left America. Baby Valerie Rena Lyons baby daughter of Mark and Florrie Lyons was 4 and a half months old. His address is 8 Wellington Road, Edgebaston. Probate records show that Florence left £135 6s 3d in effects to Mark Lyons of 8 Wellington Road.

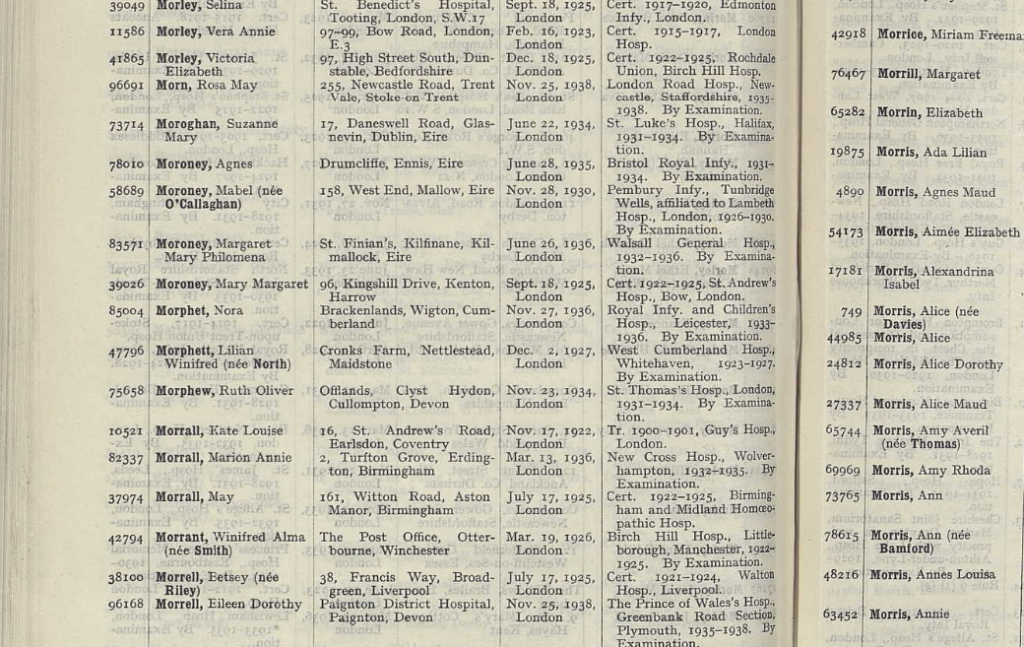

Nora’s marriage to this first widower did not last long. Mark died in 1933 in St Mary’s Hospital , Paddington ,London on 14th January 1933 . Probate was to Nora Lyons , 8 Wellington Road , Edgebaston £ 28,902 17s 10d. This same year we know from the nursing registers that Nora began her 3 year training in Leicester to become a nurse.

Her brother James was living with father James in 1924 according to the Electoral register and is working as a Railway Porter, dad still being a signalman. They are listed as James and James Jnr.

Marriage registers tell us that James Jnr married Betsy( Bessie) Jane Heslop in 1925, She had been born in Yanwath where the Morphet family had lived. Her father was also a Railway Signalman.

We learn later that they had a daughter, Dorothy in 1926 and a son, James in 1928.

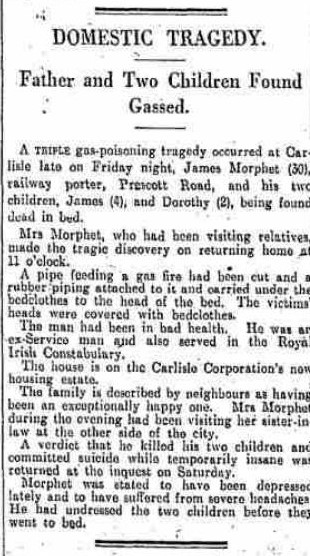

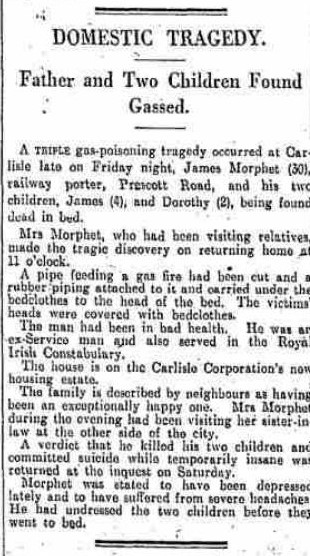

Tragedy hit Nora and her family in 1930 when her brother James , aged 30, committed suicide by gassing himself and the 2 children, Dorothy 4 and James 2, in bed. His wife had gone out for the evening to visit her sister in law. It was reported nationally and regionally that she had come home to discover this scene in the bedroom of their home at 31 Prescott Road , Carlisle – described in one newspaper as the new Corporation Housing.

James’ death reported in The Scotsman – Monday 06 January 1930

Reports mentioned that they seemed such a happy family, that he had suffered ill health for some time. The Sheffield Telegraph and the Londonderry Times reported the inquest and mention depression and bad headaches.

James ( father ) appears to have moved along Millholme Avenue at this point to number 12 to stay with his daughter Ethel Annie now Armstrong and her husband .

By the 1939 register now aged 65 he has moved again to 28 , is a retired Railway signalman and is living with Emma Bell , 62 a widow.

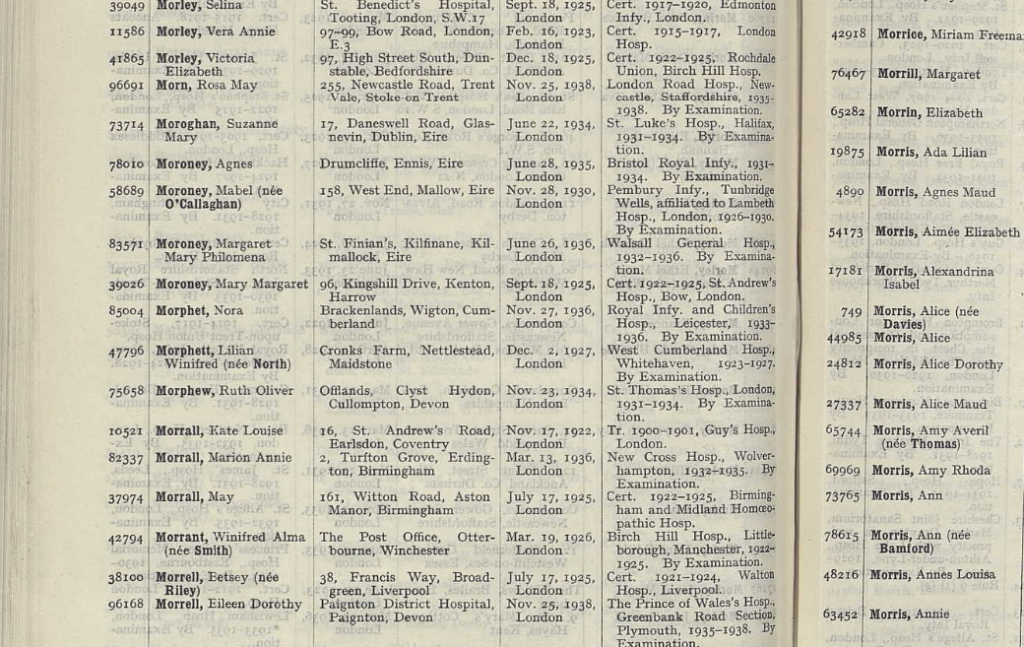

In 1933 Nora appears on the Nursing Registers for the first time , training at Leicester Royal Infirmary and Children’s Hospital between 1933 and 1936. Her registration number was 85004. She appears on the Nursing Registers for 1937, 1940, 1943 and 1946. They are revised every 3 years.

The 1937 Nursing register shows that Nora is back in Cumberland, living at 5 North Street, Maryport No trace of her can be found on the 1939 national register.

The 1937 Nursing register shows that Nora is back in Cumberland, living at 5 North Street, Maryport No trace of her can be found on the 1939 national register.

The 1940 register of nurses shows that she has moved to Brackenlands, Wigton, Cumberland and it is from there that she marries a second widower, Wilfred Isaac Witts Lomas.

The 1939 National register shows Wilfred as being 33 , a Commercial Traveller selling Tubes, of “ The Rowans” , 66 Lutterworth Road, Blaby Leicester. His wife Susan is listed on a separate page as a patient at Leicester hospital, Regent’s Lane and death registration shows that she died in September 1939.

10 months later Wilfred married Nora, 9 years his senior in Wigton, Cumberland. Coincidentally, his father was also a Railway Signalman. Could Nora have nursed his wife whilst in Leicester and some kind of bond struck? This was the second widower that she married.

At aged 42 it seems that Nora had a son, John Wilfred A Lomas born in Leicester. Electoral registers subsequently place him in Edinburgh in 1964 aged 21 living in Marchhall Crescent in the vicinity of the Pollocks Buildings of the University. He married Irene Kemlo in Abernethy, Perthshire in 1966.

Nora and Wilfred appear on the Midland, England, Electoral Register for 1962 living at 60 Swancote, Road Birmingham. It is not clear why Wilfred’s Probate listing mentions the Leicester address.

There is an indication that Nora died in Birmingham in 1984 aged 86 having outlived Wilfred by 10 years. The last official mention of her that can be found is the Nursing register where she is still listed as living at 66 Lutterworth Road , Blaby, Leicester. Death registers tell us that Wilfred died in 1974 in Leicester.

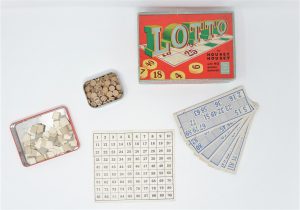

The final game I researched was called Lotto or Housey Housey, and it turned out we also had a more modern version of the game which was named Bingo.

The final game I researched was called Lotto or Housey Housey, and it turned out we also had a more modern version of the game which was named Bingo.

Ethel is to be found on a separate census return as a 15 year old servant for a miller and his wife at Morland ,Penrith.

Ethel is to be found on a separate census return as a 15 year old servant for a miller and his wife at Morland ,Penrith.

The 1937 Nursing register shows that Nora is back in Cumberland, living at 5 North Street, Maryport No trace of her can be found on the 1939 national register.

The 1937 Nursing register shows that Nora is back in Cumberland, living at 5 North Street, Maryport No trace of her can be found on the 1939 national register.