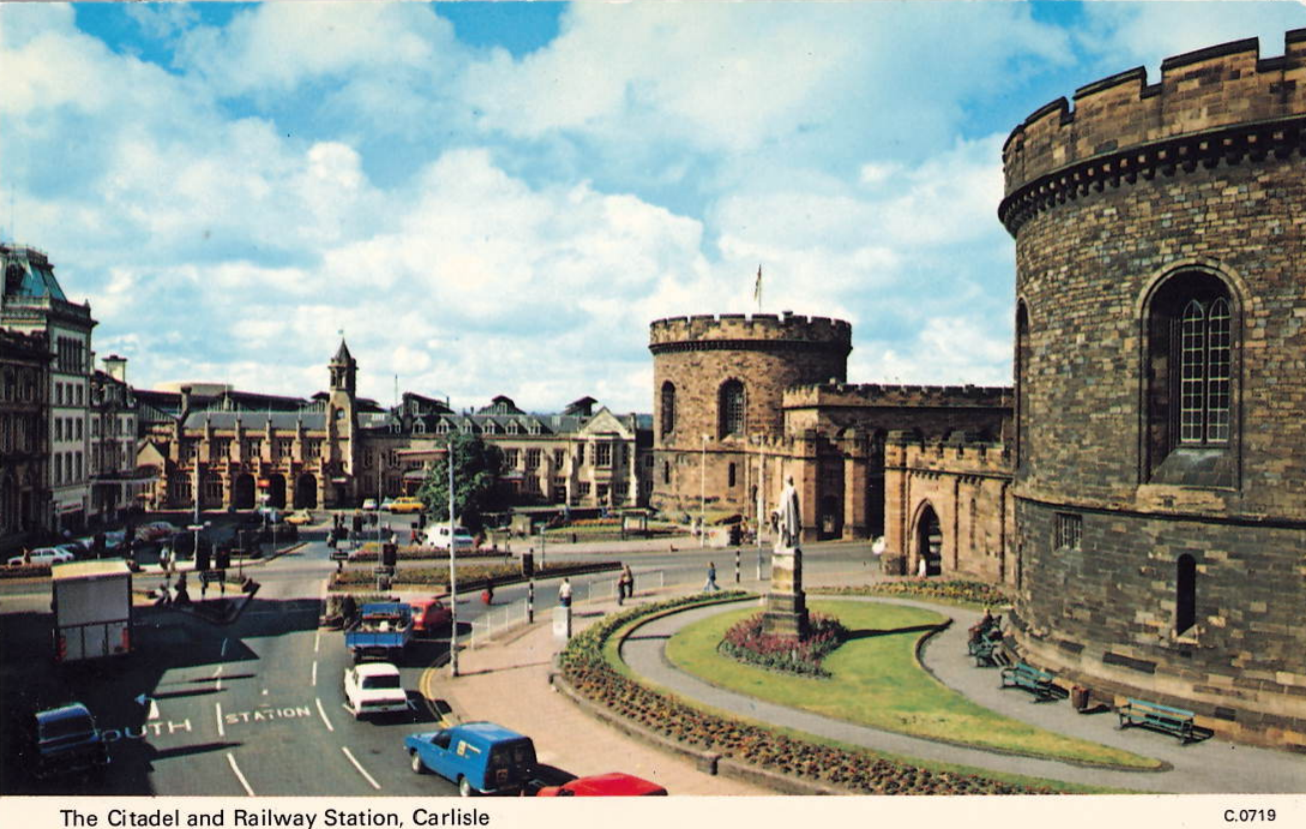

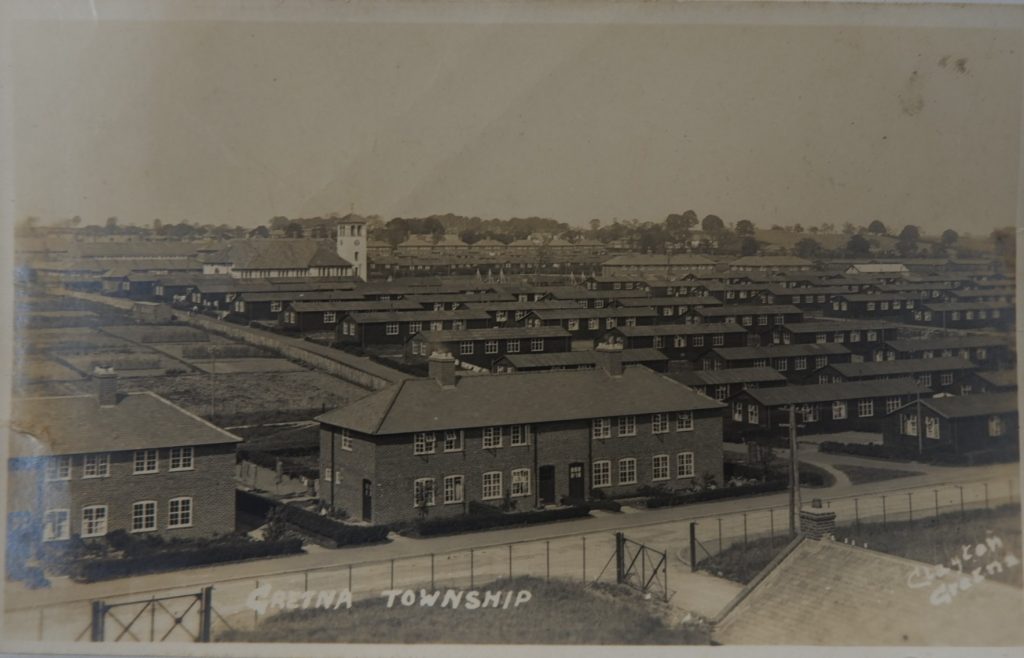

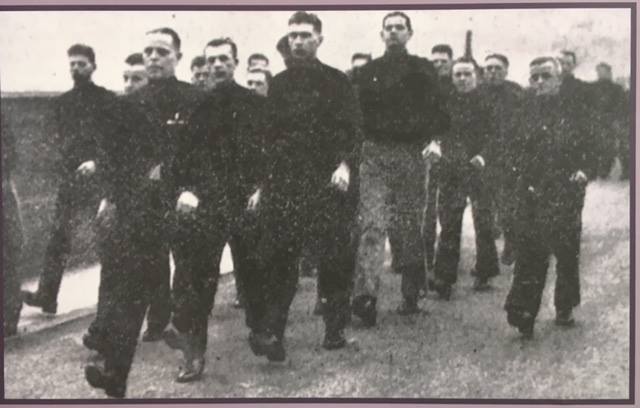

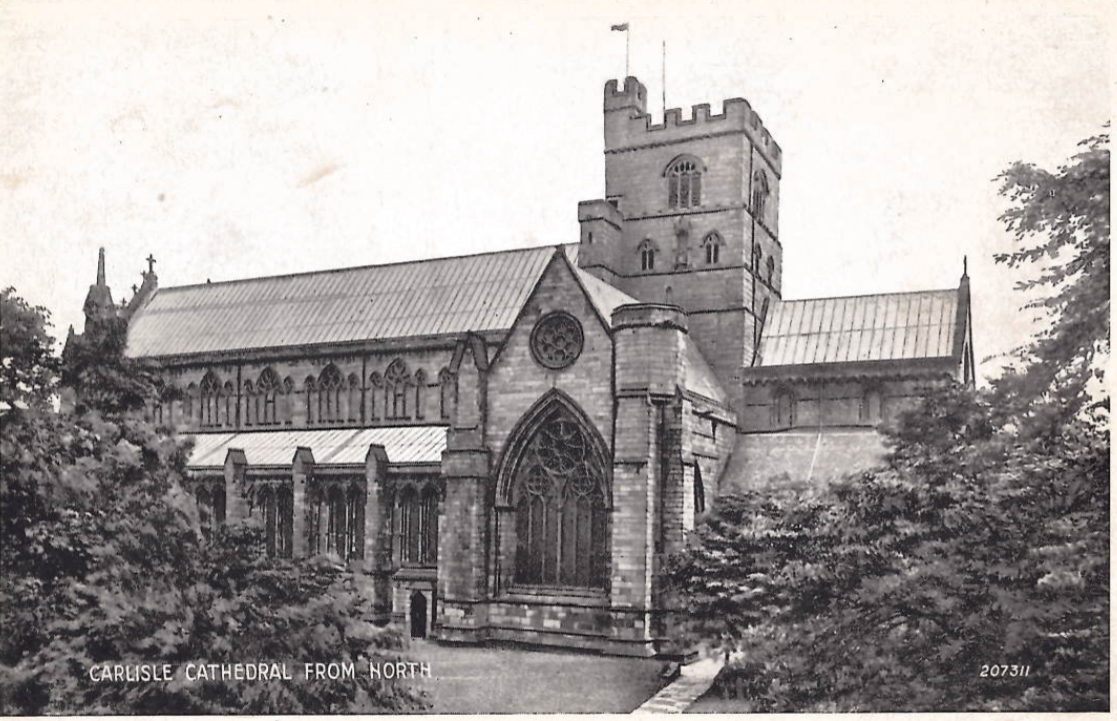

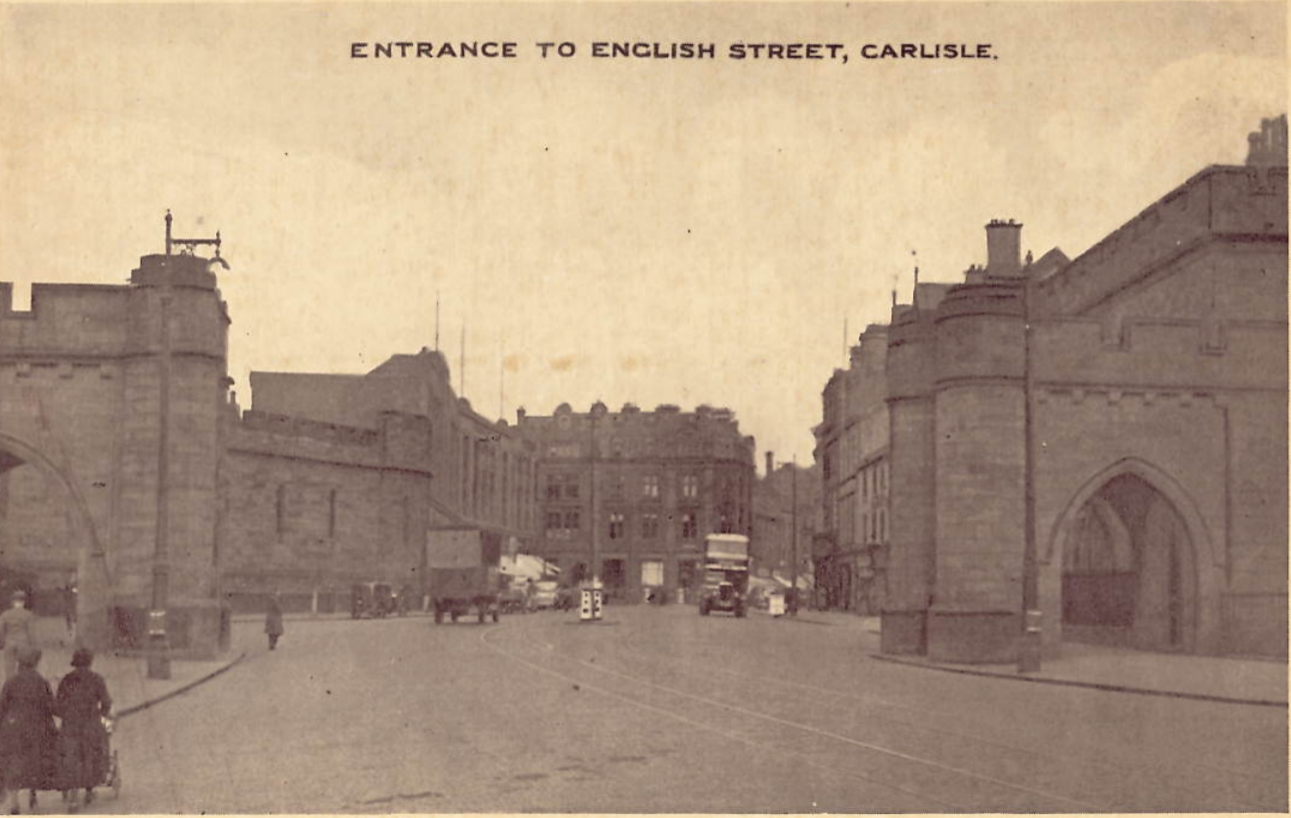

It is always very interesting to view old postcards of what the local and surrounding areas looked like in the past and how much they have changed throughout time. These postcards of Carlisle date from different time periods showing different parts of the city throughout time.

The first postcard shows Botchergate Street in Carlisle sometime around WW1.

This shows Carlisle Cathedral from the North Side.

The Museum keeps many postcards of the local area and has many more of other towns and villages nearby showing what it might have been like living there during and after the First World War.

This shows the entrance to English Street.

These postcards show some of the most recognisable streets in Carlisle that anyone who has been there or lives there would recognise which is why it is so interesting to see how they have changed overtime.