The Miracle Workers Research Project began in 2021, with research volunteers striving to find out more about the 30,000 people who worked at HM Factory Gretna in World War One. In the months since, many fascinating and previously unknown histories have been uncovered. Today, volunteer Cathy writes about her research into Miss J Drummond.

Miss J Drummond worked as a member of staff at the Dornock site of the Gretna Munitions Factory, with a tantalising entry in the Dornock Souvenir magazine providing her address as ‘Megginch Castle, Errol, Perthshire’.

Address entry for Miss J Drummond, Dornock Souvenir Magazine

From this address, it has been possible to find out something more about Miss Jean Drummond’s remarkable life and that of her family via family history websites, historic newspaper records and books.

It seems that Megginch castle is no ordinary castle, and that the Drummond family is no ordinary family, for their outstanding visionary achievements in agriculture, marine engineering and their lives of public service, amongst other things. There is an adventurous, pioneering quality of the family described in the words of John Drummond, Jean’s brother, as “the usual family spirit of being different” and there is a family motto of “marte at arte”, which John translated as meaning ‘by hook or by crook.’[i]

Jean’s family – early years at Megginch Castle

Megginch Castle is a 15th Century Castle situated on the Carse of Gowrie near Perth, Scotland, that has been in the Drummond family since 1661.[ii] It has ancient yew trees believed to date from a monastic community and is in an area known for its fruit-growing.

Jean’s father Malcolm Drummond was one of the Grooms of the Privy Chamber in Ordinary to Her Majesty, Queen Victoria. Her mother, Geraldine Margaret Tyssen-Amherst, of Didlington, Norfolk, was the daughter of William Tyssen-Amhurst, the 1st Baron Amherst of Hackney.

Jean was the oldest of a family of four children, with two younger sisters, Victoria Alexandrina and Frances Ada, while the youngest child of the Drummond family was her brother John, who became the 15th Baron Strange.

At Megginch Castle through recent generations, the Drummonds have been focused on agriculture, the soil, fruit growing and organic land management. Jean’s upbringing with her siblings included growing vegetables and flowers and keeping poultry.[iii]

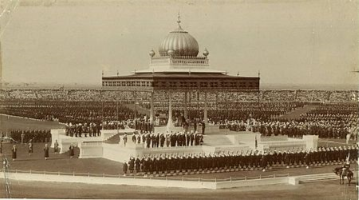

In July 1911, at the age of 20, Miss Jean Drummond was to be found attending Court at Holyrood with their majesties the King and Queen. Miss Jean Drummond was “looking very sweet and pretty in a lovely ivory satin dress with tunic of silvered chiffon and silver fringe. Train of ivory satin. Clan tartan sash and holly badge. Pearl necklace and earrings.” A whole page of the Dundee Courier newspaper is dedicated to describing the event and listing the ladies attending, with details of the ladies’ fine clothing, headlined as “Many Notable Scottish Ladies Present. Bewilderingly Beautiful Gowns.” In October of the same year The Queen, the Lady’s newspaper, describes the notable people attending the second Ball of the Perth Hunt, with a record number of nearly 500 people attending: Miss Jean Drummond was reported as present, wearing white chiffon with a tartan sash.

The onset of war

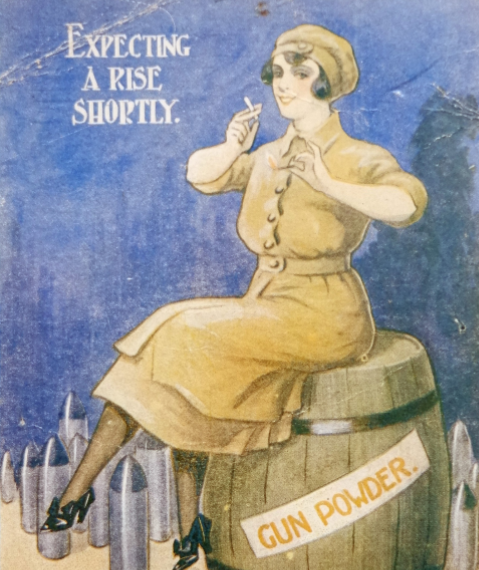

With the onset of a World War just a few years later, the newspaper stories about the Drummond family ladies are quickly transformed away from details of fine clothing, to reflect their active involvement in helping the war effort.

In 1915 a sale is held in a school for the Kilspindie and Rait Work Party to raise funds for soldiers’ and sailors’ comfort funds. The sale was “very gracefully opened” by Miss Jean Drummond of Megginch, who “spoke very highly of the good work done at Kilspindie.” In 1916, a Miss Drummond attended a meeting of the Eastern District Agricultural Committee (Perth) about the employment of women on Perthshire farms, asking if anybody had mentioned any difficulty about housing. Miss Drummond suggested that a house in a central situation in the various districts could be provided for the purpose of accommodation. Later in 1916, Miss Drummond of Megginch presided over a meeting of station workers by the Perthshire Women’s Patriotic Committee. During the month of July, 1916, 8,348 men had been supplied with refreshments at Perth station through the initiative of “Barrow Days,” having served a total of 55, 712 men up until the end of that month. Facilities at stations had proved inadequate to deal with the number of travelling soldiers, and Perth Station served the three lines of the Caledonian, the north British and the Highland. Enterprising women began to serve refreshments and this evolved into a 24-hour service of volunteers.[iv]

Perthshire Women’s Patriotic Committee: “Barrow Days” of free refreshments at Perth Station

credit: tour-scotland-photographs

Jean at Gretna Munitions Factory

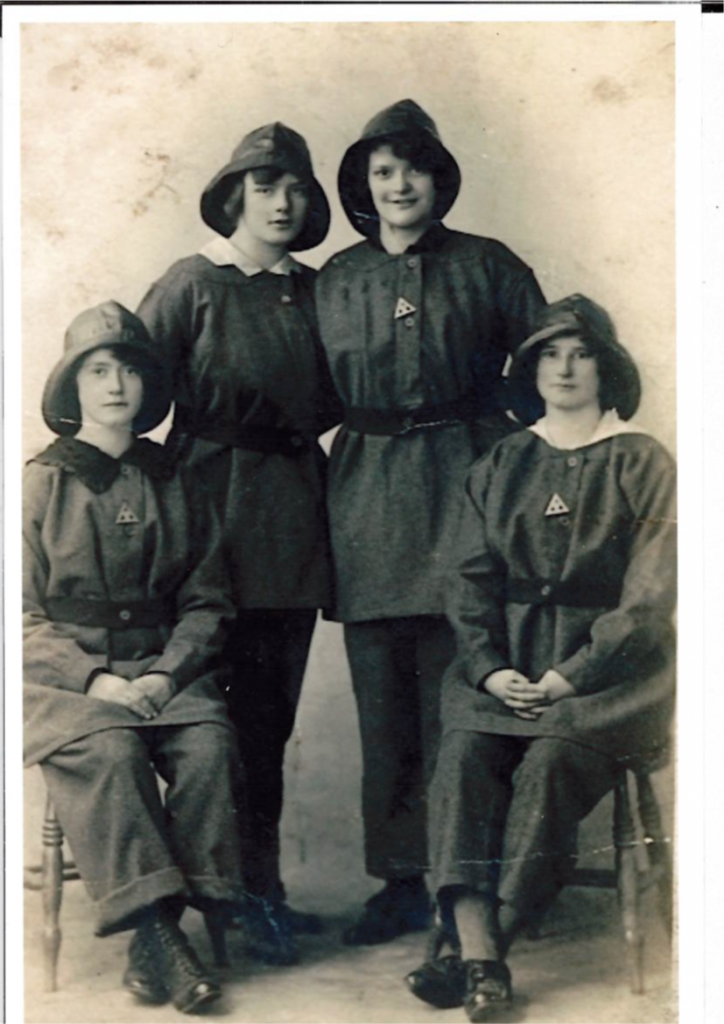

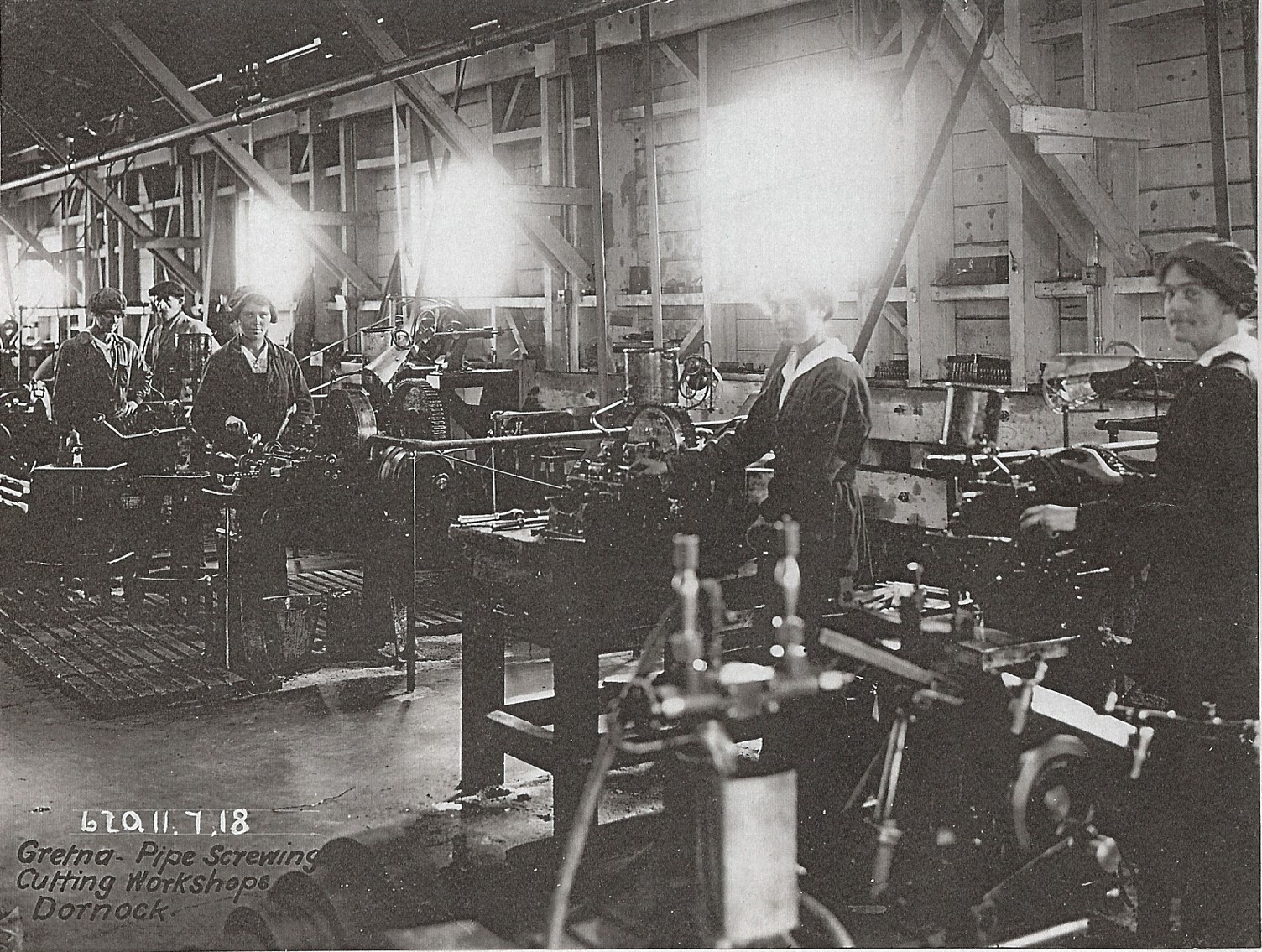

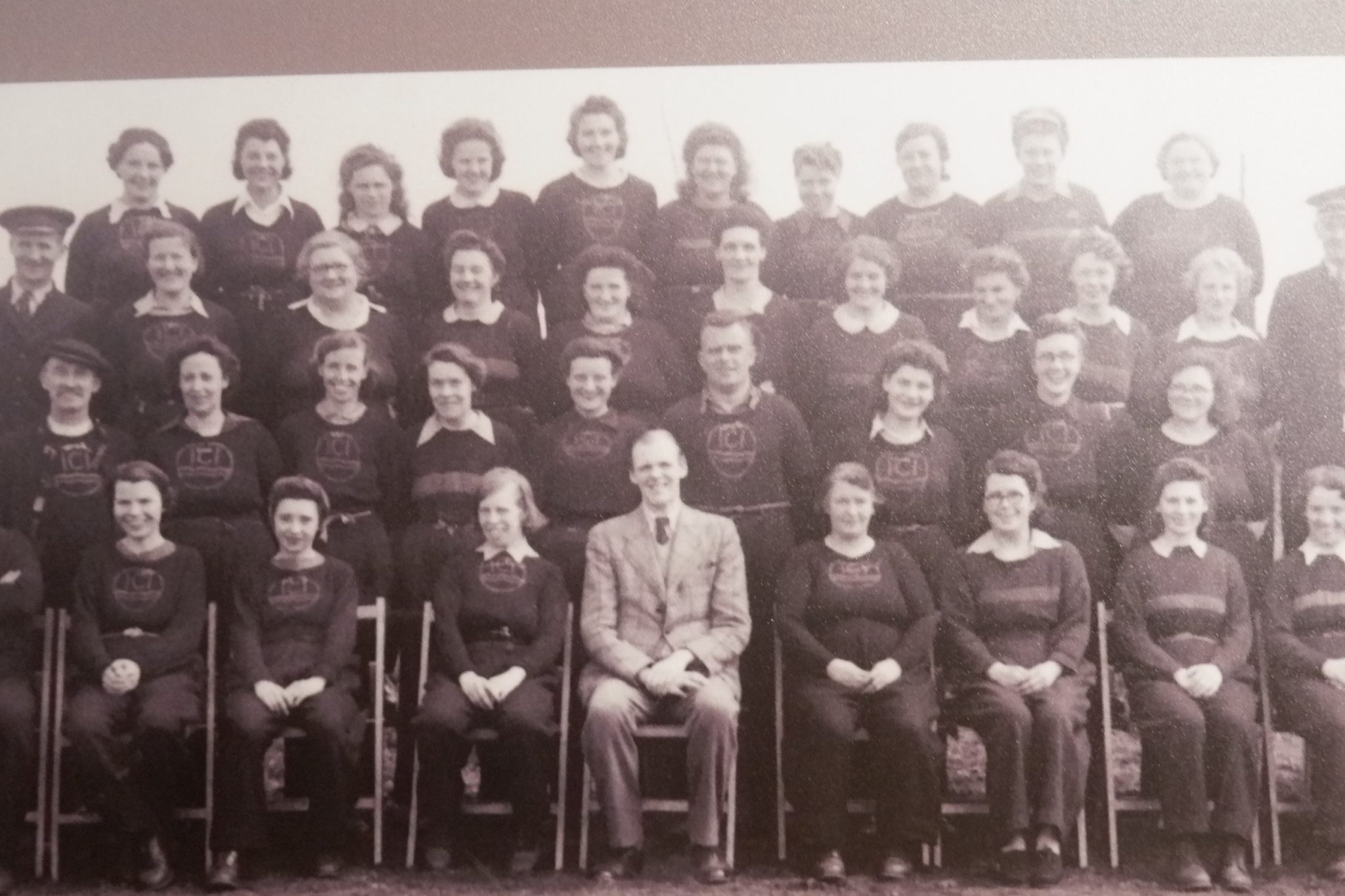

Jean made the move from Megginch Castle to the western section of the Munitions Factory at Dornock/Eastriggs as a member of staff. She would have been just 25 years old when the factory began production in 1916. In the electoral roll for Eastriggs, 1918/19, she is listed as living at A2 Eastriggs – accommodation that was a far cry from the environs of Megginch Castle.

An example of the hut accommodation at Gretna Munitions Factory.

Later, brick was used for houses and communal facilities, with Garden City architects brought in to design and build the new towns of Eastriggs and Gretna.

credit: Wikimedia commons

The electoral roll provides a job title for some staff, but there is no further information about Jean, other than the fact that she was not enrolled as a Parliamentary voter at Eastriggs. We also know that she was living with Miss Annabella Barrie, and Mrs Sophie Robertson, who was a welfare supervisor.

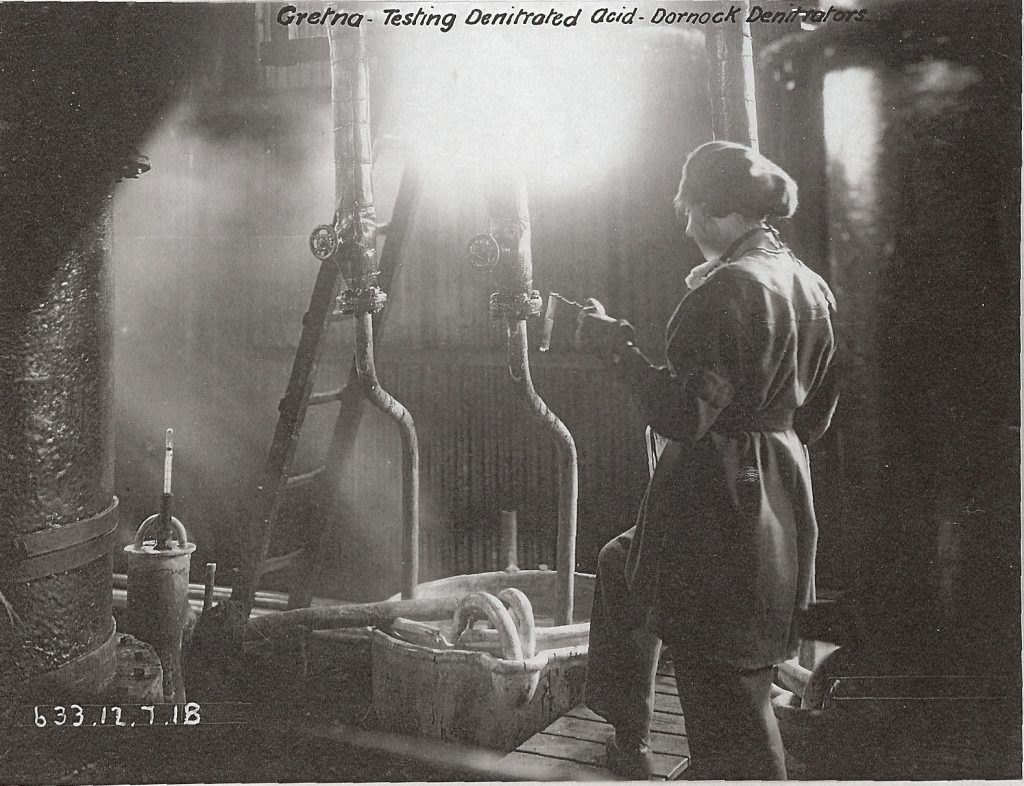

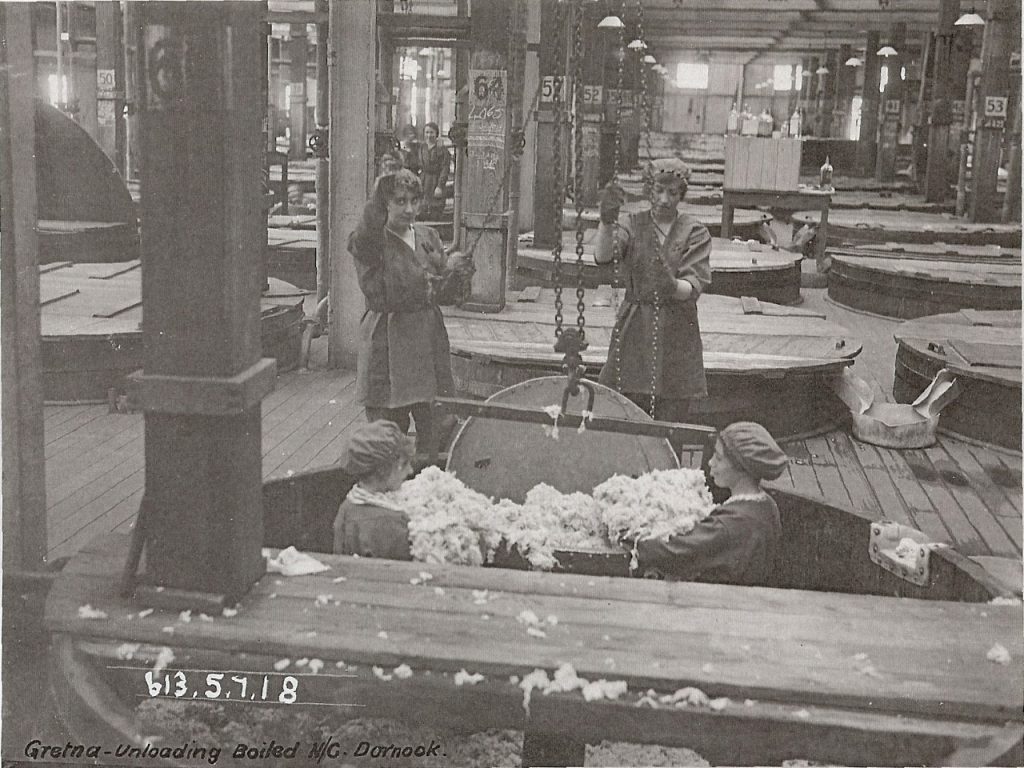

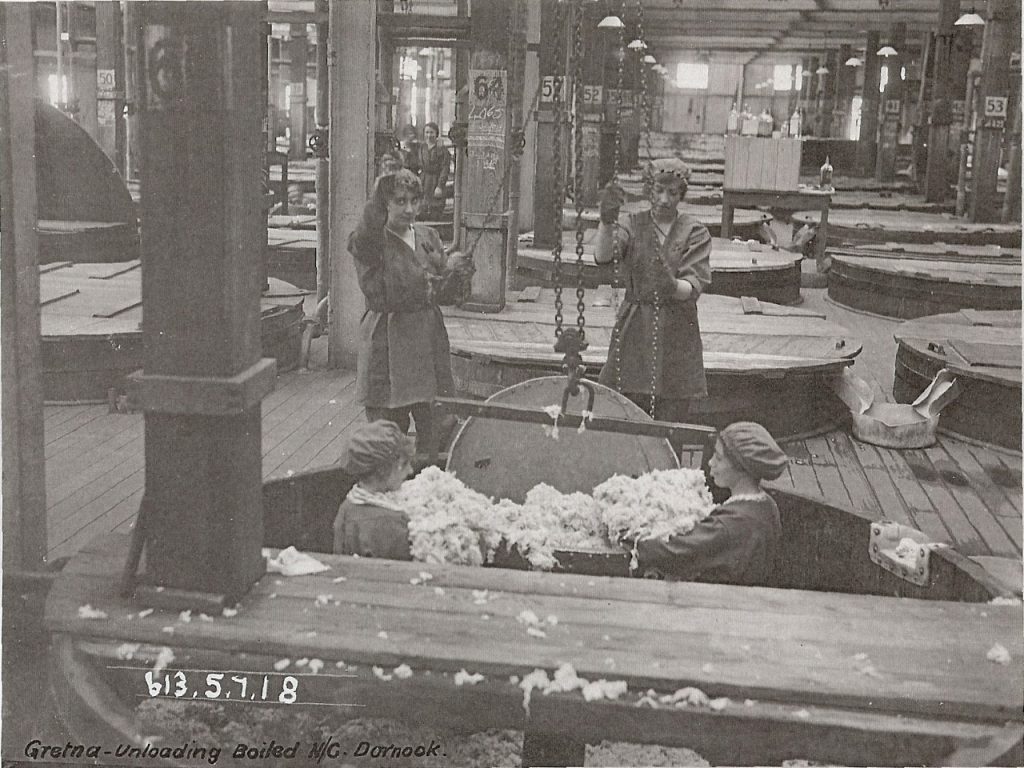

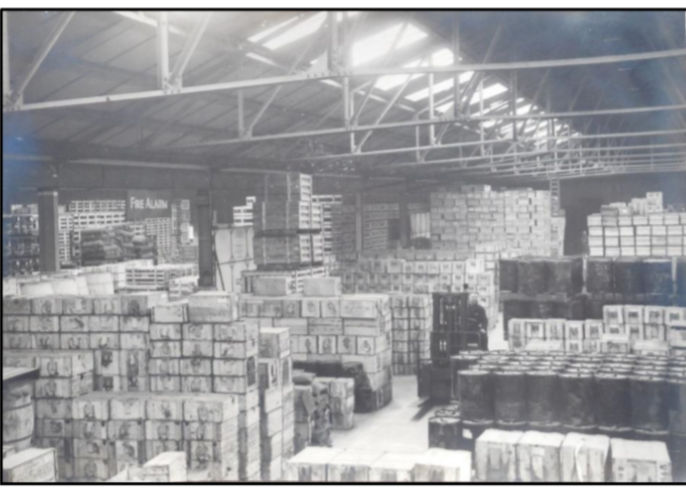

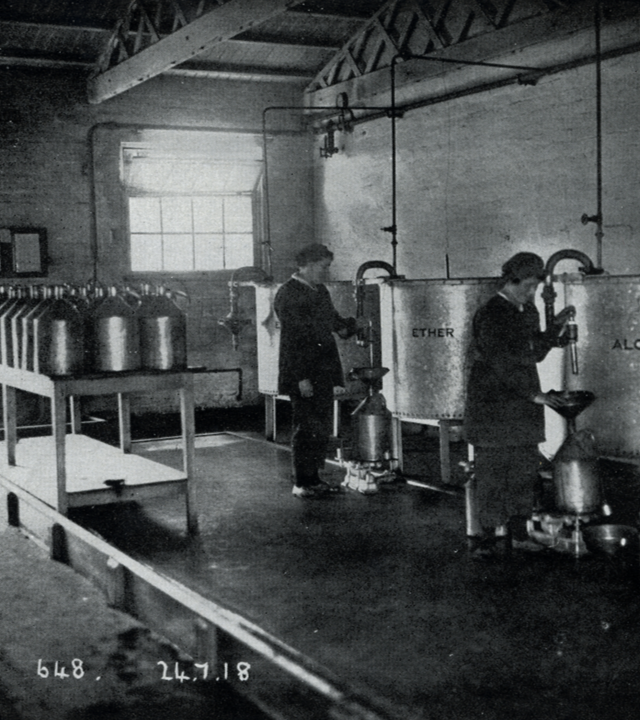

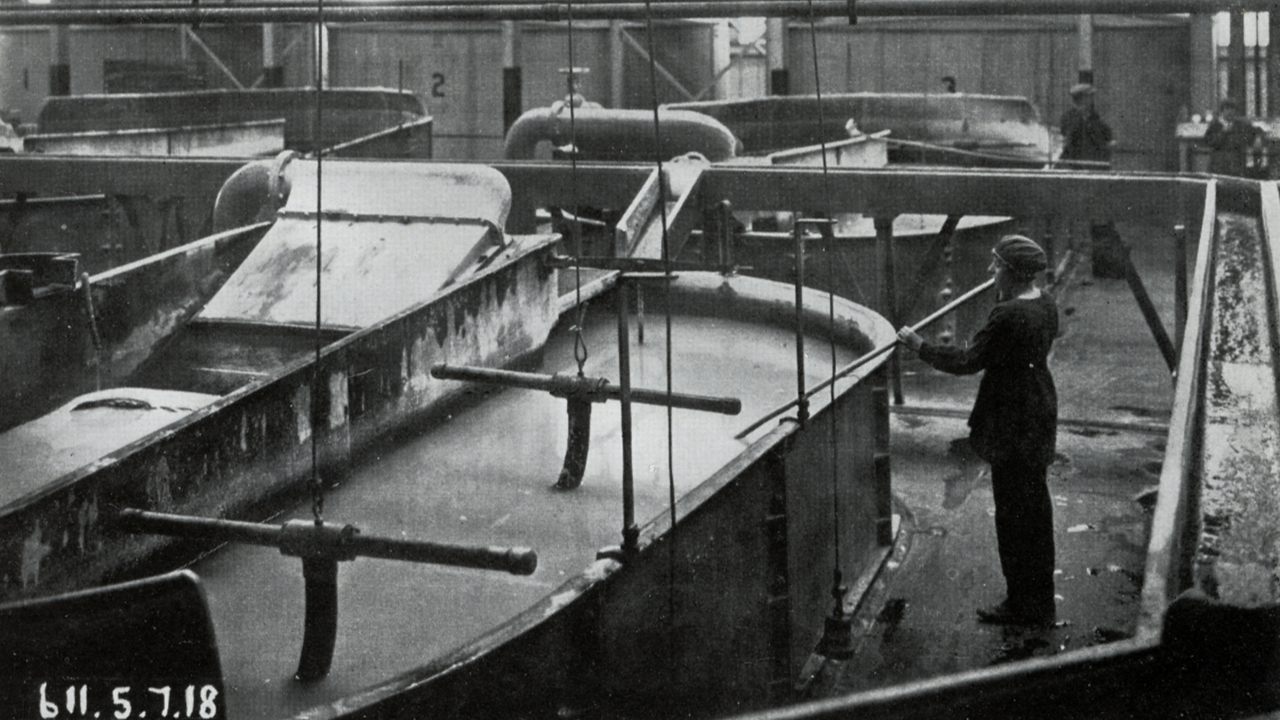

Dornock extended over 1,203 acres and was positioned at the western (Scottish) section of the 9-mile-long Gretna Munitions Factory. This section of the enterprise produced nitric and sulphuric acids, nitroglycerine and gun cotton. A new township of Eastriggs was built on a 173-acre site. Moving eastwards, Gretna was also created as a new township then, across the border to England, was located the Mossband site of factory production, near Longtown, where the final product of the propellant cordite was produced. It was at Dornock where the nitroglycerine and nitro-cotton were mixed to make a cordite paste.[v] Remarkably, the army of workers at the munitions factory at one time came to exceed 30,000 (construction workers and cordite production). In the summer of 1917, the proportion of female to male workers was about 70% to 30%.[vi]

Unloading boiled nitrocotton, Dornock

credit: Devil’s Porridge Museum archives

Perhaps from Jean’s point of view, it would have been good to know that there was some agricultural work undertaken at the site, with a photograph showing groups of girls haymaking at Broomhills:

Girls haymaking at Broomhills

credit: Devil’s Porridge Museum archives

To Lambeth and Queen Victoria Working Girls’ Club

After WW1, Jean moved from Eastriggs to Lambeth, London, to be leader/matron of Queen Victoria Working Girls’ Club. The club was founded in 1887 for local working girls at 122, Kennington Road. Activities of the club included drama, dance, folk songs, crafts and nursing. Jean was associated with the club from 1919 until at least the onset of WW2.

The Drummond sisters had a long association with Lambeth, and with Kennington Road in particular. Jean lived in a flat at 122 Kennington Road through the 1930s and right up to WW2, while her sister Frances, who was a commercial artist, lived across the road at number 143 Kennington Road, with sister Victoria, who was a marine engineer.

122 Kennington Road, Lambeth: the address of Queen Victoria Working Girls’ Club. credit: British Listed Buildings

Another World War: Jean’s experience of the Blitz

From September, 1940, right through to May, 1941, London was bombed almost every night, a time that came to be known as ‘The Blitz’. During that period, Jean and Frances were AFS (Auxiliary Fire Service) volunteers.

The night of April 19/20, 1941 was a particularly severe night of bombing. By midnight, a sub-fire station located in the Old Palace School, Poplar put out calls for assistance to south of the river (e.g. Lambeth). Jean and Frances must have travelled to duty at this extra call. The city was trying to cope with 1,400 fires, which were very scattered due to the fact that low cloud and drizzle were obscuring targets. Various crews were standing-by at the school when, at 1.53 am, the school took a direct hit from a bomb which went through the roof and down the stairwell, causing instant deaths: many people were trapped in the rubble as much of the school collapsed, and fire took hold in the remains of the building. It took until morning to put out the fire; then began the job of finding the bodies and searching for survivors. Recovery took nearly a week: bodies were taken to a temporary mortuary for identification. 34 people died that night, 32 men and 2 women. 33 of the people who died were auxiliaries. After being buried for 5 hours in the rubble, it is something of a miracle that both Jean and Frances were rescued and, along with another woman, were rushed to hospital.

The morning of 20 April, 1941: Old Palace School, Poplar, London

Searching for the bodies begins: credit Paul Chiddicks

This tragedy remains the largest single loss of Fire Brigade personnel in English history. Its full details remained untold at the time due to Emergency Defence Regulations, being unearthed six decades later by the Firemen Remembered Charity.[vii]

This bombing, however, was not the only direct experience the two sisters experienced. John Drummond, Jean’s brother, on a trip to stay with them in London to collect essential farming equipment, includes reference to their house having had a direct hit, the hostel where they had taken rooms having gone too and, as well as their wardens’ post, half the new house (in which they were still living) – and also, ‘hearing a near one coming down,’ ‘Jean had got more than a touch of the blast.’ What did the siblings talk about? Not surprisingly, John spoke about Art with Frances and about the old days, ‘when we were all kids’ with Jean:

“I found it was not done to make any reference to bombs; when I started to tell a bomb story of my own I saw, by their pained expressions, that I was reverting to the category of a line-shooter. It occurred to me that women are either much braver than men or feel things less.”i

Bomb damage to 143 Kennington Road, where Frances and Victoria lived (the Queen Victoria Girls’ Club was across the road at number 122).

credit: Walcot foundation.

The sisters moved to a flat at Restormel House, Chester Way, Kennington, then (after that too suffered bomb damage) to Tresco, 160 Kennington Road for the decades to come.

Victoria Alexandrina Drummond MBE

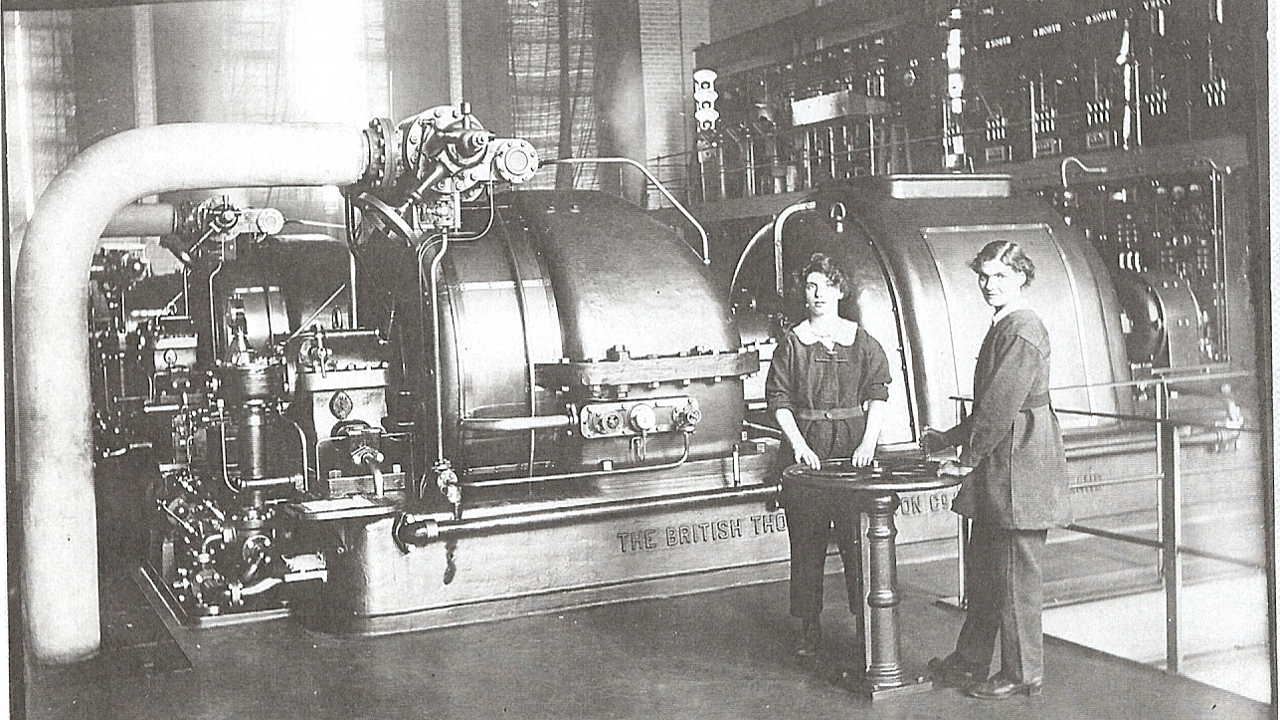

Jean’s sister Victoria, who was named after her godmother Queen Victoria, vigorously pursued her wish to become a marine engineer. After very many setbacks, and through sheer determination and hard work, during the 1920s she served on ships visiting Australia, Africa, China and India. She then found it difficult to get work in the Depression of the 1930s, but WW2 offered new opportunities – and new setbacks – that, despite her qualifications and experience, she found it impossible to get a position as a female Second Engineer. Undeterred, she continued to pursue her work tirelessly as a marine engineer, and ultimately she qualified as a Chief Engineer. Victoria was awarded the MBE in 1941, as well as the Lloyds war medal for bravery at sea. She had achieved becoming the first woman to go to sea as a marine engineer, and the first woman to become a member of the Institute of Marine Engineers (now the Institute of Marine Engineering, Science and Technology).[viii]

After Victoria saved a ship following bombing in the north Atlantic, local residents in Norfolk, Virginia, where the ship docked, gathered a collection of £400 for Lambeth. Victoria donated this to the Lambeth Communal Kitchens Committee, where a hot sixpenny lunch was provided at the Victoria Drummond Canteen, for people bombed out of their homes.

Later years

With the running of the Queen Victoria Working Girls’ Club, AFS duty during the Blitz, and other initiatives such as the sixpenny lunch, the Drummond sisters were well-respected in Lambeth. After their move to Tresco at 160, Kennington Road, years later the choir of St Philip’s Church made a point of singing Christmas carols for them.[ix]

Clearly the sisters led very close lives and, when Victoria and sometimes Frances were not travelling the world, their base together for many working years and in retirement was firmly rooted in Lambeth.

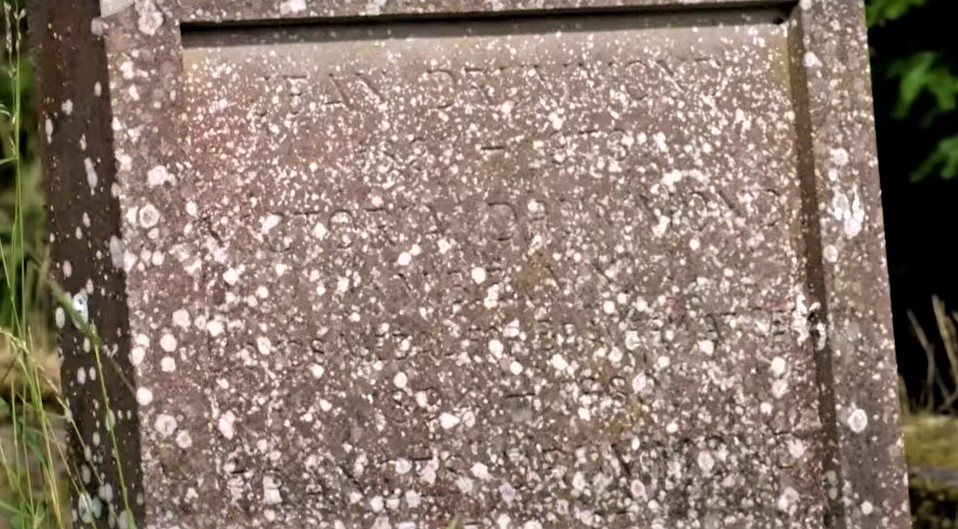

Jean died in 1974 aged 83, very shortly after the death of sister Frances in the same year. Sister Victoria died in 1978, and all three sisters are buried together at Megginch Castle.

Gravestone of the three Drummond sisters: Jean, Victoria and Frances at Megginch Castle. credit the cornpoppy.com.

Megginch Castle today: digital farmers’ market

130 years on from Jean’s birth, Megginch Castle remains in the Drummond family.[x] The orchard at Megginch holds two national fruit collections of apples and pears, with over 1,400 trees. Scottish tea is now grown there.[xi] Local producers of food and makers can sell direct to the community through a ‘NeighbourFood Market’ initiative, thus keeping brother John Drummond’s visionary ideas and organic practice of agriculture (and those of previous generations of Drummonds) very much alive to this day.[xii]

Miss Jean Drummond: a dedicated pioneer for the working girls of Lambeth and valiant AFS warden

Background reading around the Drummond family has revealed that, through the generations they have been and are, an enterprising, pioneering and visionary family, unaccustomed to resting on their laurels and refusing to be overcome by setbacks. Jean was no exception. As a child raised in a castle and attending many prestigious social occasions, any expectation for her future life was unlikely to have included working in a Munitions Factory, running a club for working girls in London for many years, and experiencing two world wars, including being bombed at home, and facing death during valiant Auxiliary Fire Service work in London during the height of the Blitz.

A life expected and a life lived: a striking contrast

There was a cohort of people who were born in the late 1800s who were destined to live through (if they were lucky), not one, but two world wars, significantly spanning ten years of their adult lives. Lives and fortunes altered drastically for men and for women, for better and/or worse. Someone like Jean, with her unique Drummond family rural upbringing, combined with attendance at the very top socialite occasions, had no doubt to adapt from the life expected. It’s incredible what Jean and other amazing ladies such as her sister Victoria and Miss Florence Catnach, who was Chief Supervisor at the Mossband site of HM Gretna Munitions Factory[xiii] witnessed living through and apparently not only adapted, but adapted with vigour. Their legacy of work at Gretna Munitions Factory, though for a relatively short period of time, seems to have set the tone for the remainder of their lives.

The contrast between Jean Drummond’s upbringing at Megginch Castle and her actual life (and that of her immediate family) is surely a particularly striking example.

[i] Drummond, John (1945) Inheritance of Dreams, Faber and Faber.

[ii] https://megginchcastle.com/timeline/

[iii] Drummond, Cherry (1994). The Remarkable Life of Victoria Drummond – Marine Engineer. London: Institute of Marine Engineers.

[iv] Burton, Anthony (2014) The Workers’ War: British Industry and the First World War, the History Press.

[v] Routledge, Gordon L (1999), Gretna’s Secret War, Bookcase.

[vi] Routledge, Gordon L (2020), Moorside: A Wartime Miracle, Arthuret.

[vii] The detail and illustration of this story has been made possible by the excellent account by Paul Chiddicks, whose Great Aunt Winifred Alexandra Peters tragically died that fateful night, aged 39. For a complete, detailed account, see: https://chiddicksfamilytree.com/2017/08/17/old-palce-school-ww2-bombing/

[viii] https://engineeringhalloffame.org/profile/victoria-alexandria-drummond

[ix] Zimmerman, Maud (1996), Edmund Walcott’s Estate: A History of the Walcot Estate in Lambeth.

[x] https://megginchcastle.com/

[xi] https://teagardensofscotland.co.uk/megginch-tea-garden

[xii] https://foodanddrink.scotsman.com/food/megginch-castle-in-host-weekly-digital-farmers-markets/

KBQ’s timeline after the war

KBQ’s timeline after the war