Researched and written by Mohammed Binghulaita Alghfeli.

Introduction

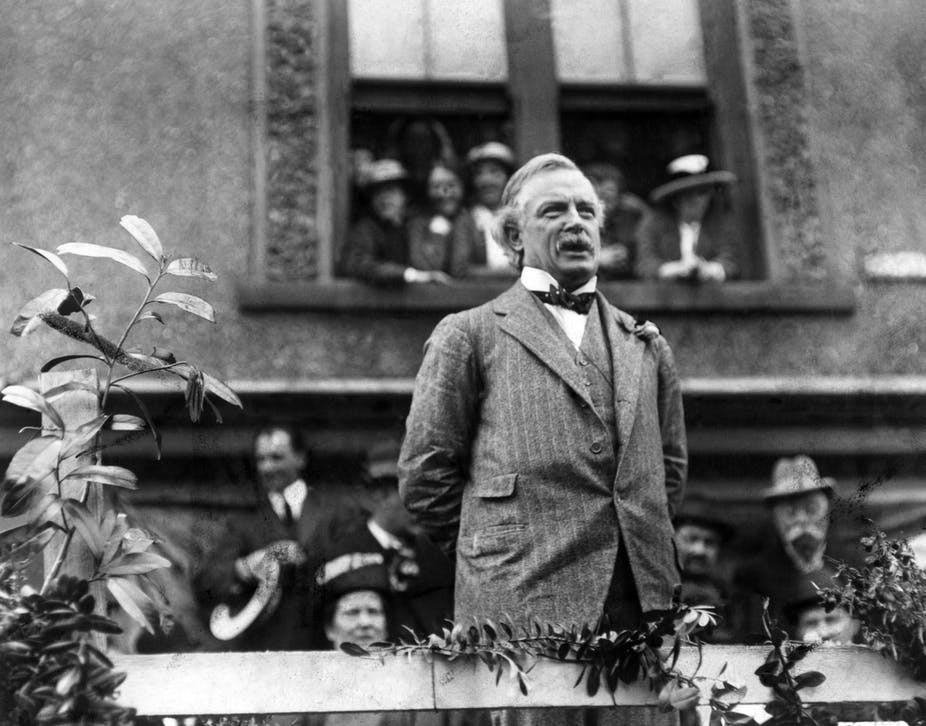

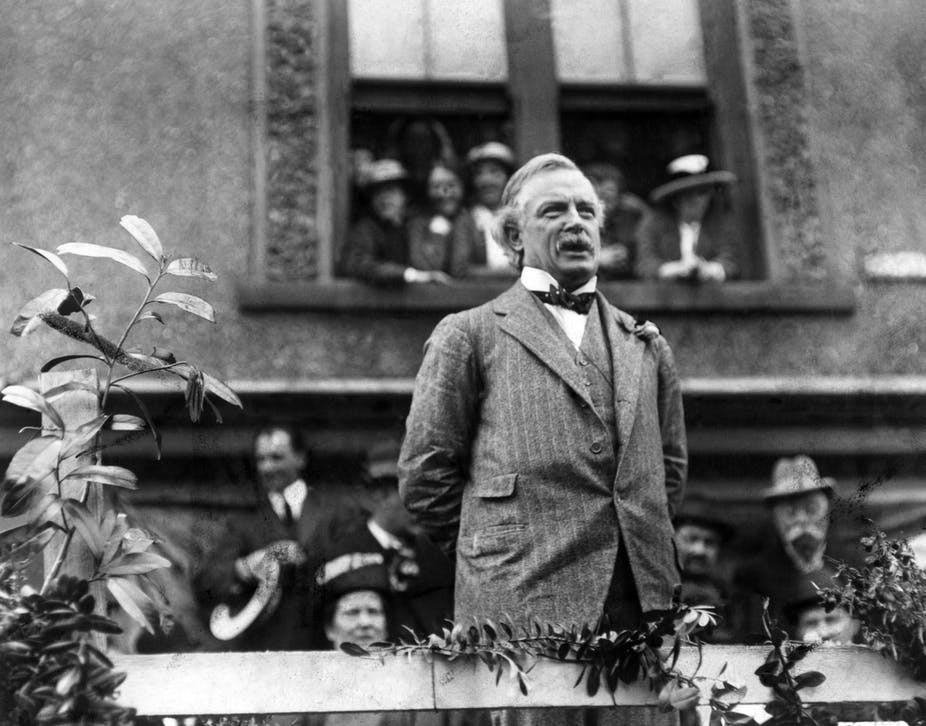

David Lloyd George pictured in 1919. Photo credit: http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a10674/

Lloyd George is one of the most popular British Prime Ministers of the 20th century. Lloyd George is best known for planting the seeds of the modern British welfare state. Although his fondly remembered as an energetic and pragmatic Prime Minister, the government roles he had before being Prime Minister are often ignored. This article sheds more light on Lloyd George’s role in the creation of Factory Gretna. Lloyd George was appointed the first Minister of Munitions and served in that role between 1915-16.

As Minister of Munitions, Lloyd George was instrumental in setting up Factory Gretna, which became the largest cordite factory in Britain during World War 1. The article argues that Lloyd George’s experience obtained from the role as Chancellor of the Exchequer was instrumental in his success as Minister of Munitions. The article also argues that it is the success of Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions that set him up to ascend to the higher office of Prime Minister.

War Time Chancellor (1908-1915)

Lloyd George was appointed the Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1908. His first major task was implementing the Liberal party’s 1906 election manifesto. A key promise was that the country would reduce military spending. Lloyd George supported the idea to reduce military spending by arguing that the country was not at war and hence government spending should be directed towards more social services (Pelling, 1989). However, conservatives launched a public campaign against the reduction in military spending. The campaign against a reduction in military spending was a success which forced the Cabinet to reject Lloyd George’s proposals.

Lloyd George’s enthusiasm to reduce military spending aligned with his core beliefs. According to Morgan (2017), Lloyd George was an opponent of warfare and was initially vehemently opposed to Britain joining the war in 1914. He only changed his opposition to the country joining the war when Belgium stated that it would refuse German requests to have her army pass through Belgian territory. As George Floyd’s anti-war stance was known, it is surprising that he was appointed as a Minister of Munitions in 1915.

Since Lloyd George was not a proponent of war, one can only wonder why Asquith appointed him as Minister of Munitions in 1915. Ahlstrom (2014) speculates that perhaps Lloyd George was appointed Minister of Munitions because of the good management and leadership skills he had shown as the Chancellor of the Exchequer. For Britain to win the war, it needed to have a competent person at the helm of its ammunitions department.

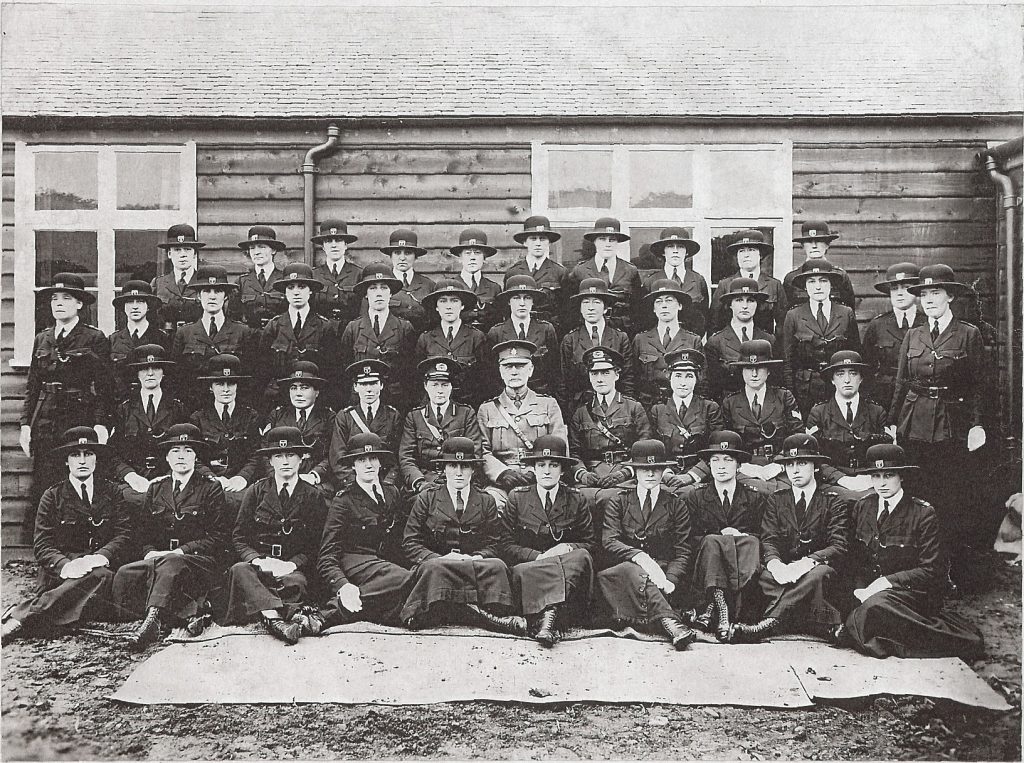

Photo credit PA/PA Archive/PA Images

Ministry of Munitions (1915-1916)

The Ministry of Munitions was created in 1915 in response to the Shell Crisis of 1915 (Greenhalgh, 2007). In addition, Miller (2021) notes that the Ministry of Munitions was also created to bring together military and business knowledge to reorganise the industry for war. Prior to Asquith creating the Ministry of Munitions, he, as Prime Minister, was in charge of the Admiralty and also ran the War Office (Quinault, 2014).

The lack of a dedicated munitions ministry had led to a shortage in the supply of weapons at the war front. Quinault (2014) argues that Asquith was not a good wartime Prime Minister. According to Quinault (2014), Asquith was more comfortable giving speeches and ignored the ammunition supply issues bedevilling the army. However, Asquith should be credited for accepting that the war effort could benefit from having a dedicated ammunitions ministry.

Minister of Munitions (1915-16)

David Lloyd George was the first person appointed to lead the Ministry of Munitions by Asquith. Unlike Asquith, David Lloyd George strongly believed World War 1 would be won through mechanisation. As Minister of Munitions, he said the “great war was a war of machinery” (Lloyd-Jones & Lewis, 2008). According to Lloyd-Jones and Lewis (2008), Lloyd George was not satisfied with the way ammunition for the war effort was being produced in Britain. Lloyd George strongly believed that Britain had to produce more ammunition for itself and its allies for itself to win the war. To increase the production of ammunitions, Lloyd George set up four large ammunitions factories around the country. One of the four ammunitions factories set up by Lloyd George was Factory Gretna in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland.

Munitions of War Act (1915)

Lloyd George was instrumental in setting up the factory by facilitating the passing of the Munitions of War Act (1915). This legislation allowed the British government to tightly monitor and control private companies who were supplying the armed forces with ammunition. Furthermore, the Munitions of War Act (1915) allowed the government to restrict employee freedoms in factories making war supplies. For instance, Factory Gretna employees were restricted to leave employment. In 1916 the law was amended to make strikes in war industries illegal, and all labour disputes were sent to a tribunal (Stevenson, 2020).

These stringent measures in the Munitions of War Act (1915) would have made workers at Factory Gretna sad because it limited the options to use when demanding better working conditions and pay. One would assume that at Factory Gretna, Lloyd George was not a popular politician because of the legislation he had introduced. A petition sent to Winston Churchill in 1918 by the Women Police at Factory Gretna provides primary evidence that some employees at the factory were not happy with their pay and working conditions.

In 1911 Lloyd George, as Chancellor, was instrumental in setting up the National Insurance Act (1911). The law laid down the basics of the welfare state by making provisions for sickness and invalidism. The National Insurance Act (1911) was pro-worker legislation, while the Munitions of War Act (1915) was restricted worker rights. The two pieces of legislation seem to show a contradictory view of Lloyd George, but a deeper analysis shows a different picture. The National Insurance Act (1911) and Munitions of War Act (1915) show a pragmatic politician who is flexible and willing to change. Lloyd George was successful in his political life because he quickly adapted to situations. For instance, in 1915, Britain needed to increase its ammunitions production, and for that to happen, the government had to restrict worker rights temporarily.

Secretary of State for War (1916)

Lloyd George did not stay long in the Minister of Munitions post as he succeeded Lord Kitchener as the Secretary of State for War in 1916. Lord Kitchener had died when HMS Hampshire was sunk on its way to Russia (Lloyd-Jones & Lewis, 2008). Lloyd George’s success in a relatively short time as Minister of Munitions made him the logical choice to replace Lord Kitchener (Greenhalgh, 2007). As Secretary of State for War, Lloyd George still had considerable influence on the goals at the Ministry of Munitions. Therefore, indirectly one can argue that his thinking as Secretary of State for War impacted the way Factory Gretna was operated.

Prime Minister (1916-1922)

Lloyd George’s tenure as Secretary of State for War did not last long as Asquith was forced to resign mainly due to his mismanagement of the war. Lloyd George became Prime Minister in 1916. He quickly began to reorganise the government so that the war could be won efficiently. The major change made by Lloyd George was the centralisation of power via a smaller war cabinet. Doing so meant that government bureaucracy was greatly reduced, which led to decisions being made quickly.

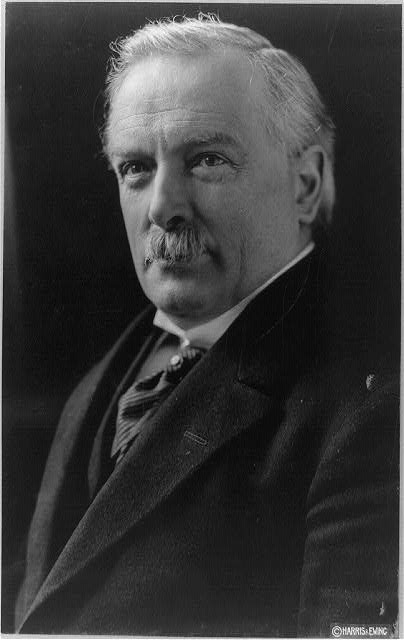

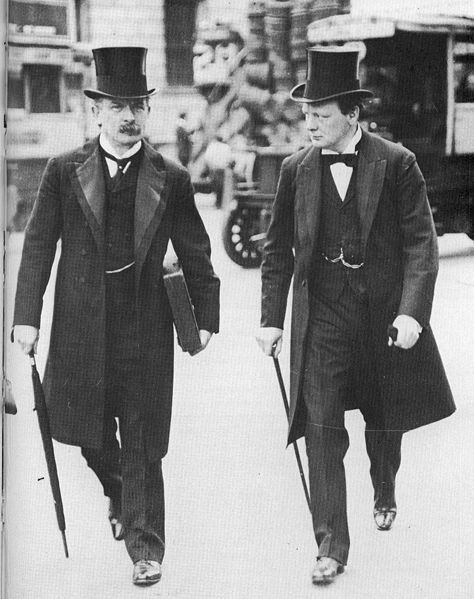

Lloyd George and Churchill pictured together in 1907. Photo in public domain.

Lloyd George also appointed Churchill as the Minister of Munitions in 1916 against the advice of many in his party. The appointment of Churchill as Minister of Munitions was greeted with hostile comments from newspapers and members of parliament (Greenhalgh, 2007). According to Pelling (1989), Lloyd George later said that his decision to appoint Churchill as the munitions minister nearly collapsed the government. However, the appointment of Churchill proved to be a good decision as production of ammunition increased at war industries such as Factory Gretna (Stevenson, 2020). To a greater extent, the increase in ammunition production is attributed to Churchill’s astute leadership.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the article discussed how Lloyd George played a pivotal role in the setting up of Factory Gretna. The article argued that Lloyd George’s experience obtained from the role as Chancellor of the Exchequer was instrumental in his success as Minister of Munitions. Lloyd George was appointed Minister of Munitions because of the good management and leadership skills he had shown as the Chancellor of the Exchequer. His success as Minister of Munitions and as Secretary of State for War opened the door for him to be Prime Minister.

Reference List

Ahlstrom, D., 2014. The Hidden Reason Why the First World War Matters Today: The Development and Spread of Modern Management. Brown Journal of World Affairs, XXI(1), pp. 201-220.

Greenhalgh, E., 2007. Errors and Omissions in Franco–British Co-operation over Munitions Production, 1914–1918. War in History, 14(2), pp. 179-218.

Lloyd-Jones, R. & Lewis, M. J., 2008. “A WAR OF MACHINERY”: the British Machine Tool Industry and Arming the Western Front, 1 91 4-1 91 6. Essays in Economic & Business History, XXVI(1), pp. 117-133.

Miller, C., 2021. The Clydeside Cabal: The influence of Lord Weir, Sir James Lithgow, and Sir Andrew Rae Duncan on naval and defence policy, around 1918–1940. The Mariner’s Mirror, 107(3), pp. 338-357.

Pelling, H., 1989. Munitions. In: Winston Churchill. London: Mcmillan, pp. 229-248.

Quinault, R., 2014. Asquith A Prime Minister at War. History Today, May, pp. 40-48.

Stevenson, D., 2020. Britain’s Biggest Wartime Stoppage: The Origins of the Engineering Strike of May 1917. The Journal of the Historical Association, 1(1), pp. 269-293.