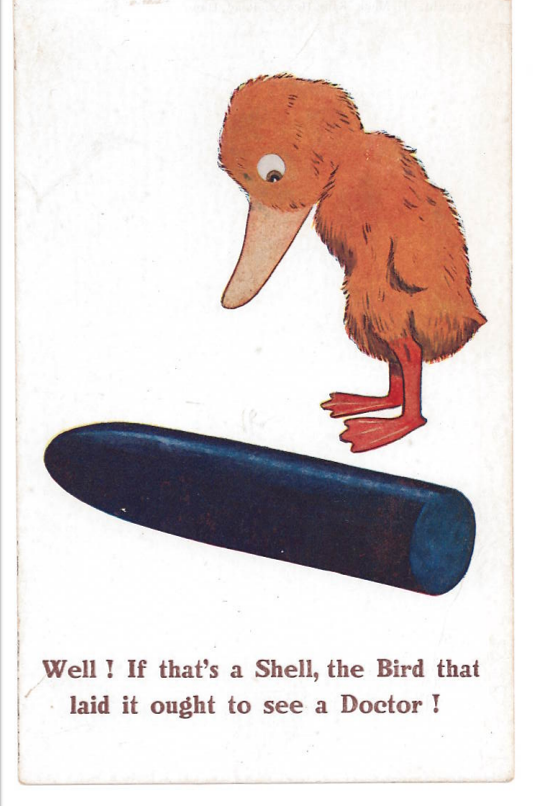

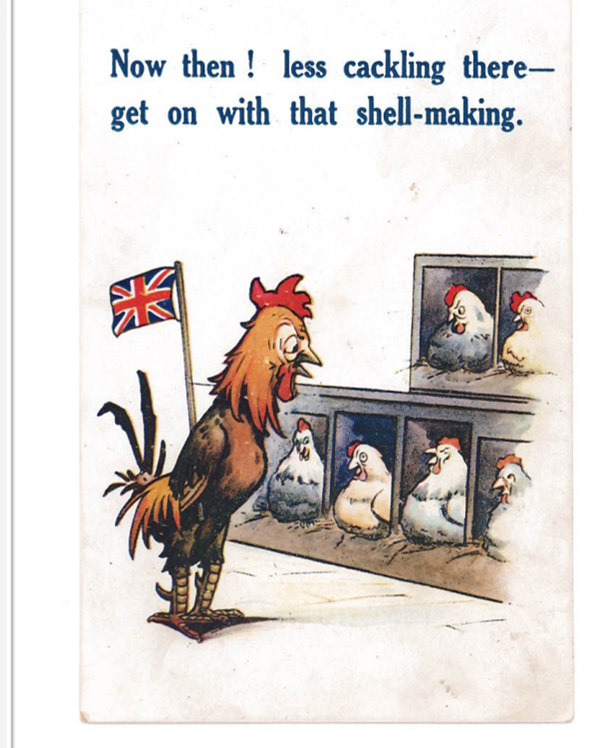

This postcard was recently sent to us by one of our friends on Facebook and has an interesting story behind it. We have some similar postcards in our collection, the shell/egg/chicken pun seemed to have amused people in the First World War.

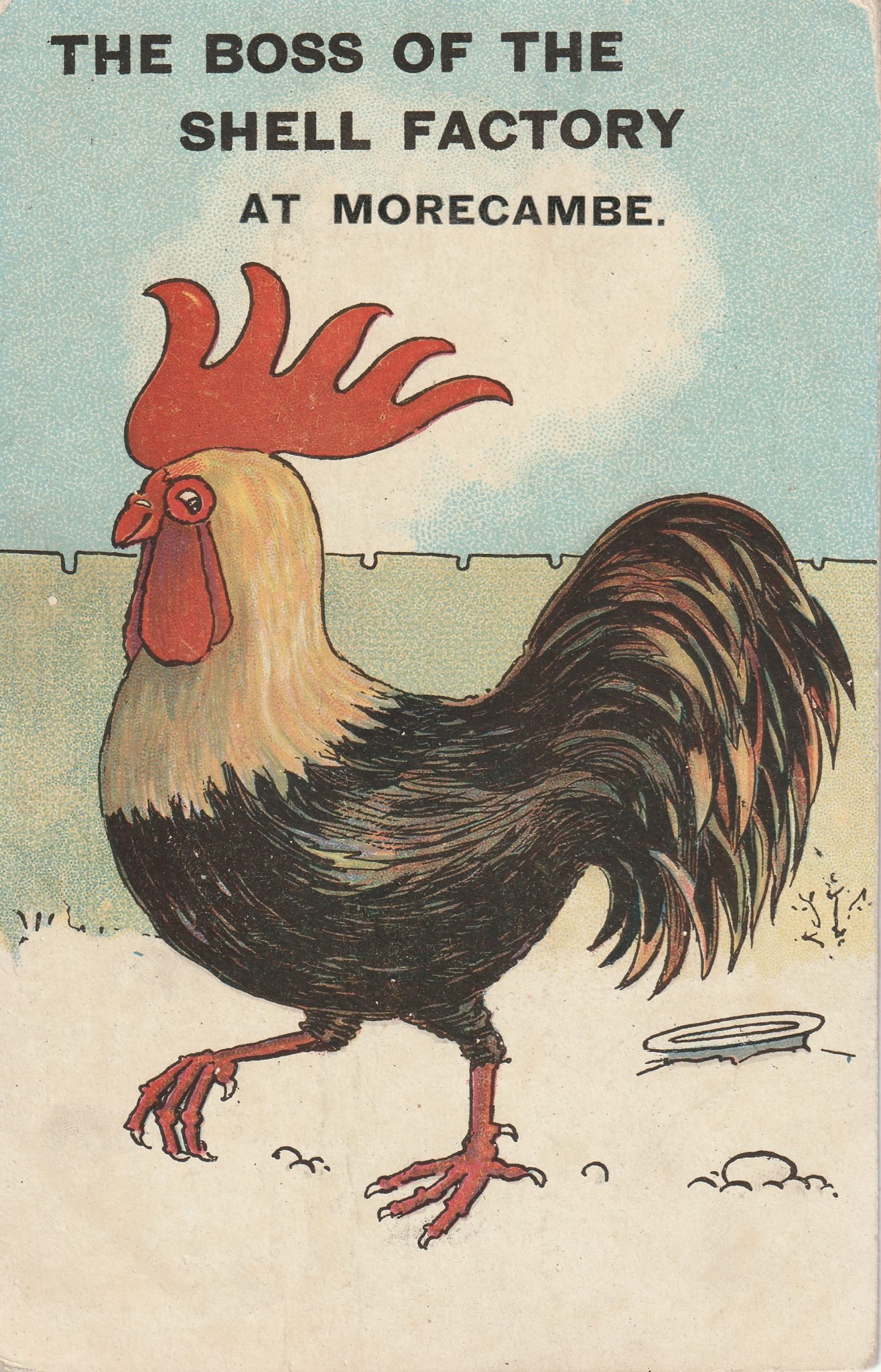

Today’s postcard from my collection is, at first glance, a Comic card from the North West seaside town of Morecambe. It shows a rooster who is more gallous than your average Glaswegian and who is strutting his stuff in the farmyard. The farmyard is his domain, and this is emphasised by the title of the card which is “The Boss of the Shell Factory at Morecambe”. This card dates from c.1917 and I would ask you to bear in mind that in those days society would draw close links with ‘male’ and ‘boss’ and ‘female’ and ‘subservient.’ The suggestion on the card is that the rooster oversees all hens who – naturally – are producing eggs. Whether he is involved in the process or not – he oversees egg / shell production.

There is however another side to this ‘humour’. This is a typical generic card where the card is produced with no town name until such times as the salesman convinces the local retailer that a specific town name fits. I have only seen two other examples of this card with one still blank and the other for Woolwich. This leads me to believe that the humour of the card was quite localised as the most obvious link between Morecambe and Woolwich is that during World War One both had a sizeable munitions factory. I think this card promotes a pun on the word ‘shell’ as while shells are certainly linked to eggs and hens they are also the main production item from a munitions factory. I look at the card again and I wonder if the object below the tail is a feeding dish – or is it an almost fully submerged shell which is intended to support the pun?

The card is undated and bears no postal markings. It has most probably been sent within an envelope or package and as the card is from father to son it was probably sent to mother and handed to the addressee. It is addressed to Master Norman Arkwright at 65 Lynwood Avenue, Darwen and reads “Dear Norman, I write these few lines hoping to see you on Saturday hoping you arrive safe and we can have a good time. From Father xxx”

It reads like a typical note written by a father to a young son in the knowledge that it will be read to the son by the mother. There is no detail other than to ensure that the child knows he will see his father at the weekend and that his father loves him.

My belief that the card relates to the World War One period (1914 – 1918) caused my heart to sink a bit when I saw the reference to ‘Master’ Norman. There was a good chance that Master Norman would be born after the 1911 Census and this could make tracing the parties to the card difficult. Additionally, Arkwright is a common name in the Lancashire area although on the positive side the market town of Darwen isn’t too sizeable. I also suspected that the forename of Norman would be relatively scarce when coupled with Arkwright. Some names just sound routine – although ‘Norman Arkwright’ didn’t.

Darwen may be small although it has its fair share of Arkwrights and none of them lived in Lynwood Road. I jumped to the 1939 Register and found that in the whole of England and Wales there were only two persons with the name Norman Arkwright. One was born in 1894 (unlikely to be called ‘Master’ after 1914) and the other on 10th June 1912. I was hopeful when I saw this (it explains why he wasn’t in the 1911 Census and ‘Master’ fits) and was certain I had found the addressee when I read that he lived in Darwen. This was Master Norman Arkwright although by 1939 he was a ‘Paper Finisher (Brown Paper)’ and was 26 years old. He was married to Lettice who was born on 23rd April 1909. There was also a 2-year-old girl named Rene living with them. She was born on 31st October 1936 and while the name Arkwright was there it had been scored through and replaced by ‘Swayles’ although I believe the numbers next to it (10/10/58) to be a date and perhaps this working register had been kept up to date because of a marriage. Marked against Norman’s name was the notation ‘Awaiting Fire Service No. Darwen Corporation’ which suggests to me that Norman served during World War II as a fireman of some capacity. (Norman died in Darwen in May 1989 and I also note that Rene did in fact marry a Brian H Swayles in 1958).

It was pleasing to find Norman, but I now wanted to know who ‘Father’ was. I found a Family Tree online which included Norman and his wife although his parents were ‘Unknown’. It took me a bit of time although I discovered the detail of Norman’s birth advised that his Mother’s maiden name was Lingard. A little bit of digging uncovered that Alexander Arkwright married Ellen Lingard in the nearby town of Blackburn in the summer of 1908. I subsequently found Alexander (aged 28 and a Cotton Weaver) and his wife of 2 years, Ellen Arkwright (aged 27 and a Cotton Weaver), living in Darwen in the 1911 Census. I also found the couple on the 1939 Register when they were both still Cotton Weavers and living at 65 Lynwood Avenue, Darwen. Yes, the address on the card.

I can find no military record for Alexander Arkwright. He would have been 31 years of age at the outbreak of the war, and I feel sure he would have come under some social pressure to enlist – unless he was in a reserved occupation. I feel sure weaving cotton wouldn’t have been a reserved occupation…although working in a munitions factory would have been. I believe that Alexander Arkwright potentially served his war by working in the munitions factory and for that reason was living away from home and his son was travelling to Morecambe from Darwen (40 miles) that weekend.

The munitions factory at Morecambe was a National Filling Factory known as White Lund. Construction commenced in November 1915 and while factory production commenced in June 1916 construction work was ongoing. Once completed the site covered 250 acres and incorporated over 150 closely packaged buildings. “By September 1917 there were 4,621 employees at White Lund, of whom 64% were women, often young women. The workers came from all over Northern England and lived in hostels and lodgings throughout the district. The Factory worked seven days a week, 24 hours a day. It was dangerous work.”

The term ‘Filling Factory’ very much describes the process. “The shells at White Lund were filled with amatol, a mixture of ammonium nitrate and TNT; the mix was melted down to be poured into the shells. 3 million shells were filled in National Filling Factory 13 during the War.”

I can date this card quite closely now. It must date after April 1911 as the Arkwright family were not at the address on the card at the time of the 1911 Census. It likely dates after June 1916 as there was no operational ‘shell factory’ to boss before then. And it most likely dates no later than 1st October 1917 as on that date the factory was totally destroyed by an explosion. Thankfully only 10 men (mainly firemen) lost their lives as evacuation procedures were followed as soon as the fire commenced, and thousands of employees had been removed from the site.

Not surprisingly the Government placed censorship on newspaper reporting and the following is from the ‘Morecambe Guardian’ of 30th May 1930. The reporter (a local man) had recently attended the auction of the former White Lund site and both he and the auctioneer were dismayed by the lack of compassion and enthusiasm shown by potential purchasers.

“THE GUARDIAN, FRIDAY, 30 MAY 1930.

WHO WANTS WHITE LUND?

BIDS AT SALE NOT HIGH ENOUGH.

MORECAMBE’S FEAR.

GIGANTIC EXPLOSION AT FILLING FACTORY.

AUCTIONEER SMILES AT POOR OFFERS FOR SITE.

“You are making me smile, gentlemen”. These words were spoken by Mr. T. Armistead, the auctioneer, at the sale of the site of the former Filling Factory, White Lund. The sale was held in a small room at the King’s Arms Hotel, Lancaster, on Tuesday. Perhaps there were thirty or more, men there, sat in chairs, with sale catalogues on their knees. Lot number three had just been withdrawn after being bid at some ridiculously low price. “You are making me smile, gentlemen”. The auctioneer took a sip of water, from a glass at his side, and the room of businessmen moved uneasily as a class of schoolboys will when spoken to by a form master for some silly prank they have committed. What an inglorious end to what, during the War, was one of the biggest Filling Factories in England. A factory which filled thousands and thousands of shells and fed thousands of guns on the Western front, being offered for sale, per building, per acre, per lot. Three miles away from the actual site, one of the places which helped to win the war, was suffering final demolition in this room filled with men, catalogues and sunshine.

EXPLOSION RECALLED, I wondered (writes a Guardian reporter) whether Mr. Armistead, if he were Lancaster or Morecambe at the time, laughed on a certain October night in 1917 when White Lund blew up in the moonlight; or how many men in that commercial room at the King’s Arms would have displayed such poker faces were White Lund being blown up instead of sold up? Perhaps these men were strangers from afar who knew no more of White Lund than the censored news which appeared in the newspapers following the explosion. Probably few of them remembered so much as linked the two things together in any way. In those printed catalogues there might have been a little introduction giving some details of the romance, honour and terror the factory brought to Morecambe. The first shattering explosion which seemed to be just outside the windows of every house in Morecambe. A few moments of silence; and then gardens, yards and the streets filling with alarmed men, women and children in various stages of undress. Excited questions as to whether it was an air raid and the anxious scanning of the sky for the sight of a Zeppelin — we, in Morecambe, had always been led to believe that we lived too far from an enemy country to be reached by an aeroplane. Then a sudden glare shooting into the sky and paling the moonlight, followed by another deafening explosion, the tinkling of falling glass, and the shouts of “It’s White Lund, it’s White Lund,” People scurrying to Hest Bank, Heysham and Overton – anywhere to get away from these glares which filled the Eastern sky and crashes which echoed and echoed in the hills across the Bay. The unforgettable (unfortunately) sight from Heysham cliffs of debris being flung into the air – followed by shattering crashes as dumps of shells exploded. The knowledge that if the magazines went up, Morecambe would go up with them; this fear in everyone’s heart and other emotions. All these things might have formed an introduction to the sale.

WHERE FIREMEN DIED. As it was, land on which firemen had stood and died, was offered and then withdrawn. No wonder the auctioneer said that it made him smile. Perhaps it was the smile of the businessman, but it might have been a smile from a sentimentalist, bitter in either case. There were unknown possibilities in that room of men. I did not know who the man sitting next to me was. A prospective buyer? Before offering the seven lots for sale, Mr. Armistead said that he had been asked to offer the site as a whole, but as it had been advertised as being sold in lots, he would adhere to this and not disappoint the majority of clients. The site as a whole! Was the big man in the light tweed suit, and smoking a cigar, representing the Fox Film Company? He seemed oblivious of the rest of the room, or of the auctioneer, but stared at the window and the sunlight. Was he seeing a second Hollywood, or was he a representative of Airways Ltd., seeing his firm’s aeroplanes flying across Lancaster? But if Foxs were there, they were not ‘talkies’ for there were hardly any bids from the room and all the seven lots were finally withdrawn, the auctioneer remarking, “Anyone who wants to buy them now will have to do it privately – and it will cost him more.”