Trans Day of Visibility and Trans History

Today is the International Trans Day of Visibility, an annual event to celebrate transgender people and to raise awareness of the continual discrimination trans people face in our world. As a museum, it is our responsibility to share history with the public, and we consider it important to recover the histories of people who maybe traditionally haven’t had their stories told. Trans and gender non-conforming people, like many marginalised groups, have often been left out of the popular historical narrative.

Trans history is a dynamic and growing area of research. However, historians have faced challenges in writing on this subject. Archival sources are often lacking, and even where there are sources many are ‘produced by people looking from the outside in—law enforcement officers, judges, newspaper reporters.’[1] Even labelling historical individuals as trans can be complicated; I have found both Susan Stryker’s and Emily Skidmore’s approaches helpful in the writing of this blog. Stryker uses the term transgender to ‘refer to people who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth.’ Skidmore argues in her book True Sex: The Lives of Trans Men at the Turn of the Twentieth Century that ‘people have moved from one gender to another for a very long time. And transgender history looks at that movement.’[2]

Trans history is a dynamic and growing area of research. However, historians have faced challenges in writing on this subject. Archival sources are often lacking, and even where there are sources many are ‘produced by people looking from the outside in—law enforcement officers, judges, newspaper reporters.’[1] Even labelling historical individuals as trans can be complicated; I have found both Susan Stryker’s and Emily Skidmore’s approaches helpful in the writing of this blog. Stryker uses the term transgender to ‘refer to people who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth.’ Skidmore argues in her book True Sex: The Lives of Trans Men at the Turn of the Twentieth Century that ‘people have moved from one gender to another for a very long time. And transgender history looks at that movement.’[2]

The Devil’s Porridge Museum tells the story of H.M. Factory Gretna, and the thousands of munitions workers who lived at worked there in World War One (WW1). Although our focus is on Gretna, we also seek to tell the wider stories of munitions workers across the UK from 1914-1918. And one of those stories focuses on a person who, for a sustained period of time, moved away from the gender they were assigned at birth.

*A quick note to say that in the following section of this blog post, descriptions and terms used to refer to the individual at the time will be mentioned. These terms are not acceptable today, and may be triggering for some readers. However, I have included them because I believe it demonstrates the societal and historical context in which this individual was surrounded. I have also chosen to mainly refer to this person by their birth name, only because this was the name that this person went by for the majority of their life. In addition, I’ve also referred to the person using they/their/them pronouns, although quotations from contemporary newspapers do refer to them as ‘she.’*

Ellen Harriet Capon and Charles Brian Capon

I first read about Ellen Harriet Capon in Angela Woollacoot’s classic book on munitions workers, On Her Their Lives Depend. Woollacoot writes that Ellen ‘crossed-dressed’ and states that the story ‘is valuable because…it alerts us to the fact that there is still much we do not know about women workers’ sexual choices.’[3] I wholeheartedly agree with Woollacott’s assessment that Ellen’s story is valuable, but I think that it tells us about the complexities surrounding Ellen’s gender identity as well as her sexual choices.

I first read about Ellen Harriet Capon in Angela Woollacoot’s classic book on munitions workers, On Her Their Lives Depend. Woollacoot writes that Ellen ‘crossed-dressed’ and states that the story ‘is valuable because…it alerts us to the fact that there is still much we do not know about women workers’ sexual choices.’[3] I wholeheartedly agree with Woollacott’s assessment that Ellen’s story is valuable, but I think that it tells us about the complexities surrounding Ellen’s gender identity as well as her sexual choices.

Ellen Harriet Capon was from a large working-class family; they were the oldest of five siblings born to John, who worked as a warehouseman in a wool warehouse, and Ellen (nee Barker), who before her marriage had been a general servant.[4]

In 1914, the First World War broke out when Ellen was just fourteen. From the newspaper articles written about Ellen in early 1918, it appears that from 1916-1918, they worked in a factory as a wire-cutter under the name Charles Brian Capon.[5] Charles even had a military protection certificate in his name.

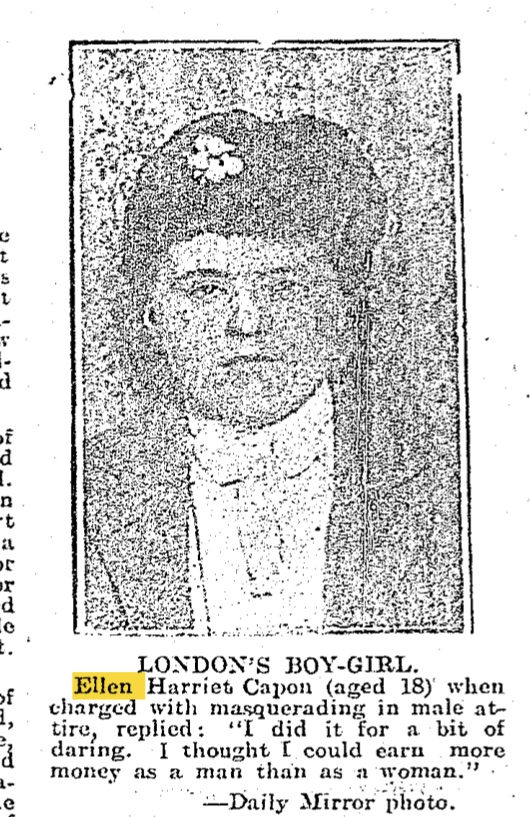

Ellen was charged with ‘masquerading in male attire’ at Lambeth Police Court on January 18th 1918.[6] They’d only been discovered upon turning eighteen, having attended a recruiting office in Brixton.[7] Men over eighteen would have been conscripted into military service, but Ellen informed the recruiting office that ‘they could not call her up, because she was a woman.’[8]

Ellen was described in the many newspaper reports as ‘is a sturdy girl of 18, her brown hair, now cut short, curls round her head and sets off her chubby face, making her pass very well for a handsome boy of refined features.’[9]

Ellen stated to the arresting sergeant that: ‘I did it for a bit of daring. My mother is seriously ill. I thought I would earn more money as a man than as a woman.’[10] This is a pretty clear statement of Ellen’s motivations for assuming a male identity—that the extra wages would provide much needed additional income for the Capon family. The arresting officer even asked Capon ‘“Have you any other reason for wearing men’s clothes?” She replied, “No.”’[11]

This seems like clear evidence that Capon’s two years presenting as a man was simply one of necessity, making a misogynistic capitalist system work better for them. However, I think other points complicate this interpretation of Capon’s story.

Ellen Capon’s arrest made headlines around the world, and multiple newspaper stories characterised them as ‘the girl-boy’[12] and said they were ‘masquerading as a man.’[13] Like with many other examples of gender non-conforming people in the past, Ellen’s story was mediated by the press and the court system, as their arrest and subsequent conviction was played out in the media. However, Ellen also gave interviews about their experience, to a News of the World Reporter and to a Lloyd News Representative. In these interviews, Ellen tells their story in their own words.

‘Asked as to whether she had any difficulty in keeping up her role as a boy, Miss Capon said there was none. She went to the city every day, nobody being any wiser. “But I have got quite used to boy’s clothes.” She said, “Really now I hardly know myself in skirts. I have got some of the wirework to do at home, and I shall continue that work until I can get on the land. I am anxious to do all, because the land girls wear special uniforms like what I have been used to of late.’[14]

This quote is revealing in a number of ways. Firstly, it speaks to the totality of Capon’s identity as a man from 1916-1918—they presented themselves publicly ‘every day’ as one. It also shows that there was some reluctance on Capon’s behalf to resume the cultural expectations of women—that of wearing skirts. Capon didn’t associate themselves as someone who wears skirts. They also clearly stated that they aspired to work in an industry that allowed girls to wear trousers in the future. Capon’s years of presenting as a man had clearly made them more comfortable with wearing trousers as opposed to skirts. Whilst I am no way arguing that this is conclusive, or even persuasive evidence, that Capon considered themselves a man, I am arguing that Capon’s statements reveal that their conception of their gender identity was complicated. As with Stryker’s approach to trans history, Capon moved away from the gender that was assigned to them at birth. This ‘move away’ may have only been for a limited time. However, it appears to have been a significant move—both for the numerous newspapers that reported on the story and for Capon themselves. Capon’s arrest was an event worth reporting on – a munitions worker who was assigned female at birth successfully presented as male for a significant amount of time without being discovered.

Capon told the News of the World reporter that:

‘I cogitated for a long time, and finally I determined to become a ‘man…I was only brought into constant daily contact with one other employee and he was a man, and we called each other ‘mate.’ He never suspected that I was a girl; at least I have no reason to think that he did so. We were working just as man and youth would do, consulting each other on business matters and carting on at our special job. I enjoyed the life very much, and did my share of the work after I gained competency just as an experienced male hand would have done…I got so accustomed to being a ‘man’ that I never felt awkward in male company. My boyish appearance disarmed suspicion.’[15]

Capon’s statements—that they presented as male because of the increased pay, that they ‘determined’ to be a man, that cutting off their hair was a ‘feminine sacrifice’ and they ‘enjoyed the life’ [of a man]—all reveal the complexities that were involved in the construction of gender identity for Capon.

In the end, Ellen was ‘bound over to be of good behaviour for twelve months’[16] and fined £10.[17] In the historical records I’ve uncovered, it appears as though Ellen Capon lived out the rest of their life by presenting as a woman. In the 1939 register, they were still living on Camden Hill Road, where they’d grown up, alongside their siblings. [18] Ellen worked as a ‘lampshade wire worker’ and was recorded as a female. Ellen died in 1978 in Plymouth.

This interpretation is of course complicated by societal attitudes towards gender non-conforming people, as well as the inability of surviving sources to capture records of those who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth. As can be seen by Ellen’s case, much of the evidence for trans and gender-conforming people’s existence in the past came from court and legal documents—written about them not by them–and in many cases, criminalising their gender expression. Whilst this post is not intended to impose our current understanding of trans identities onto the past, there is an equal importance to the recovery of people with variant gender identities across history. Like other marginalised groups, trans people’s histories have been actively suppressed.

Ellen Capon’s story is not only important to enrich our understanding of munitions workers during WW1 or the experiences of people whose gender identity changed at points in their lives, but also to illustrate the complexities of identities. Ellen may have presented as a man because, as contemporary newspapers posited and as they said in interviews, male workers got higher wages than women and the Capon family was in need of the additional income. Equally possible is that Ellen’s experience’s while presenting as a man for two years complicated their understanding of their own gender identity and changed the way they navigated their world—by aspiring to continue in job roles where they could wear trousers and be more ‘masculine.’ Ellen could have, as the sparce historical records suggest, lived out the rest of their life as a woman. However, these records and a societal pressure to conform to the norm may not have captured the complexity of Capon’s gender identity.

Trans and gender non-conforming history needs to be told, in all its complexities. Ellen was one of thousands of munitions workers during WW1, and their story is important to our understanding of the historical context. For resources on gender identity, click here.

Further Reading on Trans History:

- https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2018/what-is-trans-history-from-activist-and-academic-roots-a-field-takes-shape

- https://www.theproudtrust.org/resources/trans-resources/trans-history/

- https://www.bl.uk/lgbtq-histories/articles/transgender-identities-in-the-past#

- https://acosmistmachine.com/2015/11/24/dr-james-barry-and-the-specter-of-trans-and-queer-history/

- https://medium.com/@jackdoyle_76250/the-trans-take-towards-a-trans-public-history-deb1bc9d822b

- https://transstudiesuk.wordpress.com

- https://www.publicmedievalist.com/transgender-middle-ages/

- https://theconversation.com/lgbt-history-month-forgotten-figures-who-challenged-gender-expression-and-identity-centuries-ago-153815

- https://www.historyextra.com/period/modern/historians-view-transgender-issues-history-sexuality-gender-trans-lgbt-gay-rights/

- https://www.backstoryradio.org/blog/the-language-of-transgender-history-and-visibility/

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/531351/pdf

[1] https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2018/what-is-trans-history-from-activist-and-academic-roots-a-field-takes-shape

[2] https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2018/what-is-trans-history-from-activist-and-academic-roots-a-field-takes-shape

[3] Angela Woollacoot, On Her Their Lives Depend, (University of California Press, 1994), p. 39.

[4] John William Capon, 1911 Census Return for 5 Camden Hill Road, Upper Norwood, retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk; Ellen Barker, 1891 Census Return for Willesden, Middlesex, England, retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk.

[5] ‘Two Years as a Male Factory Worker’ Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 19th January 1918, p. 2.

[6] ‘Two Years as a Male Factory Worker’ Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 19th January 1918, p. 2.

[7] ‘Two Years as a Male Factory Worker’ Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 19th January 1918, p. 2.

[8] ‘Girl’s Masquerade’ Lancashire Evening Post, 19th January 1918, p. 3.

[9] ‘Her role as a boy’ Larne Times, 26th January 1918, p. 6.

[10] ‘Two Years as a Male Factory Worker’ Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 19th January 1918, p. 2.

[11] ‘A Girl’s Masquerade’ Westminster Gazette, 19th January 1918, p. 3.

[12] ‘The Girl-Boy’ Liverpool Echo, 21st January 1918, p. 3.

[13] A Girl’s Masquerade’ Westminster Gazette, 19th January 1918, p. 3.

[14] ‘Her role as a boy’ Larne Times, 26th January 1918, p. 6.

[15] ‘Girl’s Masquerade’ Ashburton Guardian, 9th April 1918

[16] Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 28th January 1918, p. 4.

[17] ‘Masqueraded as Man’ The Tewkesbury Register, and Agricultural Gazette, 2nd February 1918, p. 3.

[18] ‘Ellen Capon’, 1939 Register for Camden Hill Road, retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk;

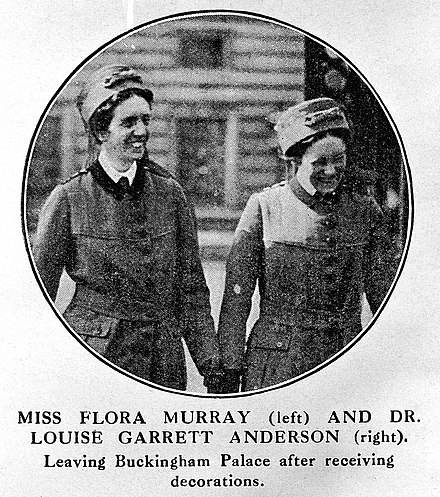

After graduating Flora worked as a medical officer at the Belgrave Hospital for Children before getting a job as an anaesthetist at the Chelsea Hospital for Women. In 1912, she co-founded, with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the Women’s Hospital for Children. The hospital’s purpose was to care for the working-class children of the local community, and its motto was “deeds, not words.”—which might give you a slight clue to the two co-founders’ women’s suffrage leanings.

After graduating Flora worked as a medical officer at the Belgrave Hospital for Children before getting a job as an anaesthetist at the Chelsea Hospital for Women. In 1912, she co-founded, with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the Women’s Hospital for Children. The hospital’s purpose was to care for the working-class children of the local community, and its motto was “deeds, not words.”—which might give you a slight clue to the two co-founders’ women’s suffrage leanings.