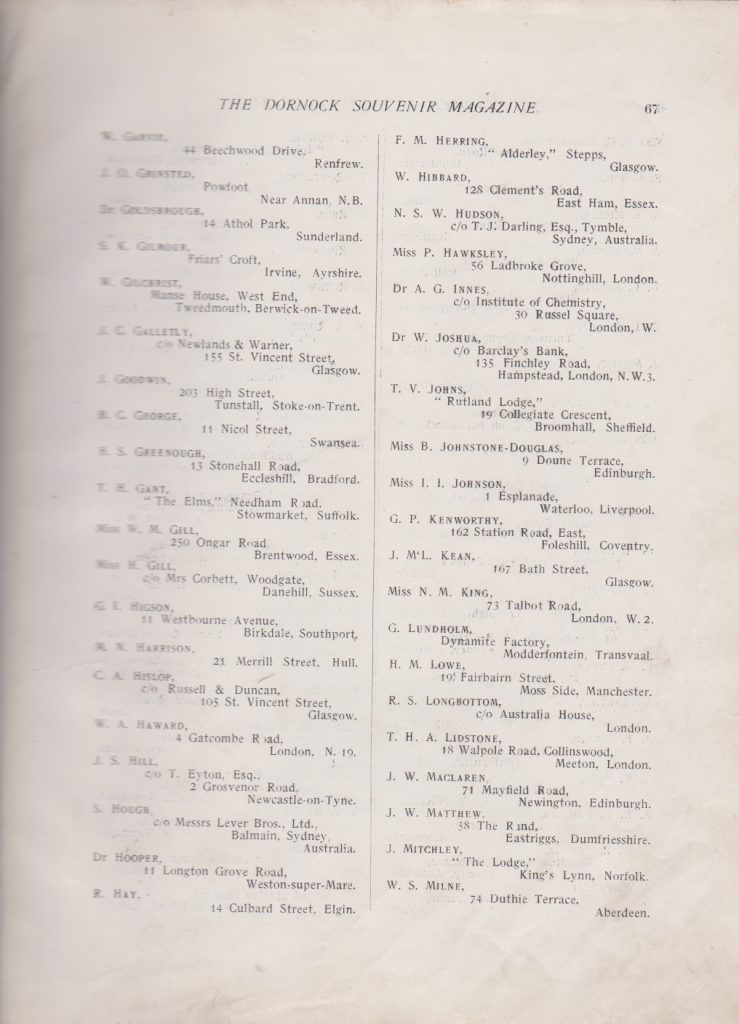

Worker of the Week is a weekly blogpost series which will highlight one of the workers at H.M. Gretna our volunteers have researched for The Miracle Workers Project. This is an exciting project that aims to centralise all of the 30,000 people who worked at Gretna during World War One. If you want to find out more, or if you’d like to get involved in the project, please email laura@devilsporridge.org.uk. This week Research Assistant Laura shares volunteer Peter’s research into Helga Gill.

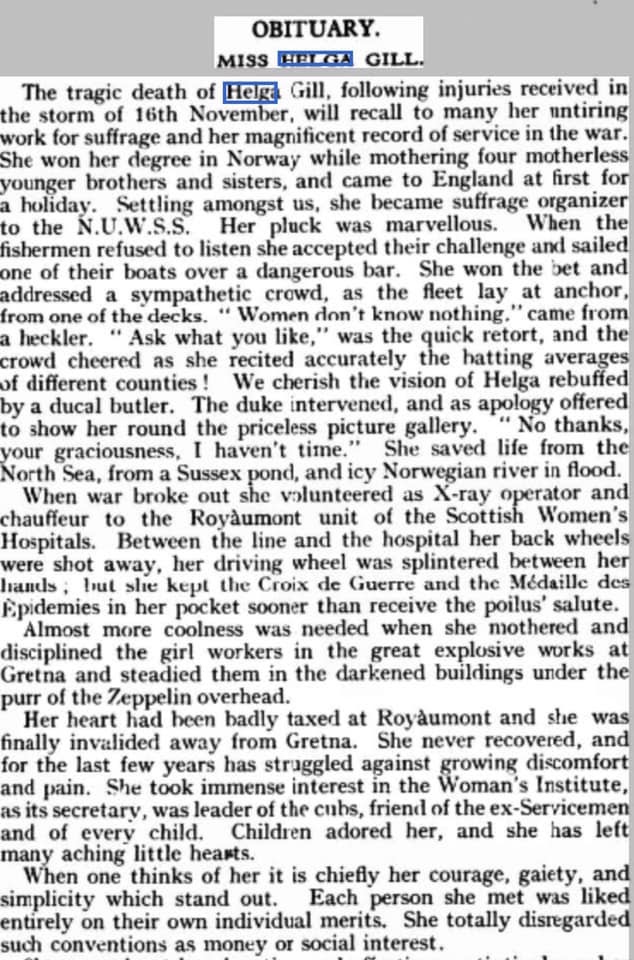

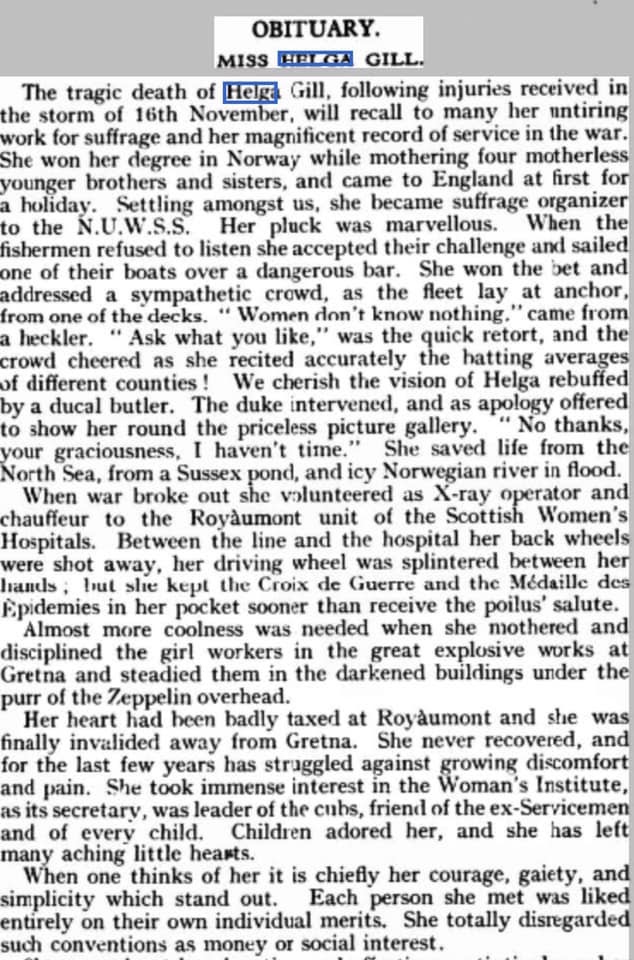

We only found out about Helga’s connections with HM Factory Gretna in an obituary written after her sudden and untimely death in 1928. Published in The Woman’s Leader, a publication closely associated with the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), it is mentioned:

“She [Helga] mothered and disciplined the girl workers in the great explosive works at Gretna, and steadied them in the darkened buildings under the purr of the Zeppelin overhead.”[1]

So how did this woman who seemed at first glance to have connections the women’s suffrage movement end up at working at HM Factory Gretna? One of our volunteers, Peter, was determined to find out!

Helga Gill was born in Bergan, Norway, in 1885. Her parents were Johan Klerk Gill and Karen Marie Ottilia Gill, and Helga grew up the oldest of six siblings. Having completed her education in Norway, Helga went on holiday to Britain, and it was there that she became acquainted with the Corbett family.

The Corbett family were a prominent political family then based in East Grinstead. Marie Corbett was a poor law guardian, suffragist and supporter of the Liberal party. Her husband, Charles, was a barrister and MP elected in 1906 for the Liberal party. Their daughters, Cicely and Margery, were both feminist activists.

Cicely Corbett Fisher. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. (1913).

It was at a celebration party for Charles’ recent election to parliament in January 1906, that Helga first enters the historical picture. According to Mapping Women’s Suffrage, Helga appeared on a platform alongside the Corbett family.[2] However, it wasn’t until 1908 that Helga began to appear regularly in newspaper articles for her suffrage activism.

As a Norwegian woman, Helga had been able to vote in national elections in her own country provided she could establish that she made a minimum income or if she was married to a male voter from 1907. These requirements were abolished in 1913, when universal suffrage was established in Norway.[3]

Helga participated in the Worcester by-election in 1908, speaking to local audiences and putting pressure on candidates to declare whether or not they supported women’s suffrage.[4] She ‘made herself stiff’ chalking notices on to the pavement, and drove a ‘press cart’ that was stocked with copies of Votes for Women to be handed out upon the release of WSPU prisoners.[5] She began giving lectures, [6] and took part in local election activism in Chelmsford.[7] Mapping Women’s Suffrage states that by this point she was an NUWSS organiser, and regularly travelling the country to spread the suffrage word![8]

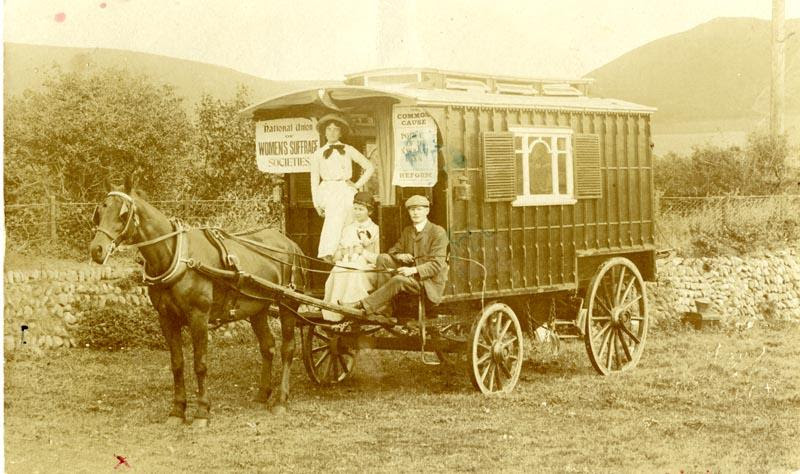

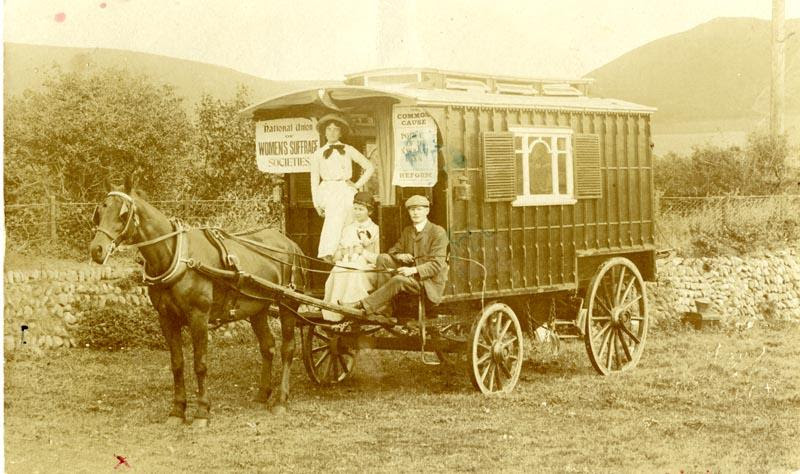

Helga pictured doing suffrage work

This hard work only continued in 1909 and beyond. In 1909 she was appointed organiser for Lancashire, as well as participating in by-election campaigns in Edinburgh, Stratford-Upon-Avon and Mid Derbyshire. She spent a month in Wales, and in the summer undertook a horse-drawn caravan campaign across the country with fellow NUWSS supporters.[9]

Like so many suffrage activists, Helga was dedicated to the cause, and spent the years before the outbreak of war in 1914 criss-crossing the country, giving talks and spreading the message. Her perspective as a Norwegian woman who, in her own country possessed the vote, was a valuable one and was often highlighted in promotional material.[10] By 1912 she was a paid employee of the NUWSS, as Organiser for Oxford, Berks, and Bucks. In that same year, she was sent on a tour of Ireland by the NUWSS.[11] Writing about her after her death, Helga’s colleagues gave a sense of her character:

‘Her pluck was marvellous. When the fishermen refused to listen she accepted their challenge and sailed one of their boats over a dangerous bar. She won the bet and addressed a sympathetic crowd, as the gleet lay at anchor, from one of the decks. “Women don’t know nothing,” came from a heckler. “Ask what you like,” was the quick retort, and the crowd cheered as she recited accurately the batting averages of different countries! We cherish the vision of Helga rebuffed by a ducal butler. The duke intervened, and as aplogy offered to show her round the priceless picture gallery. “No thanks, your graciousness, I haven’t time.”’[12]

Even the famous leader of the suffragists, Millicent Fawcett, noted ‘the delightful personality of the late Helga Gill.”[13]

But in 1914 war broke out, and the NUWSS pivoted to aiding the war effort. One of their war projects was the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service (SWH). Sprearheaded by pioneering doctor, Elsie Inglis, and funded by donations, the SWH was a groups of medical units staffed entirely by women. With bases established in France and Serbia during the war, the doctors, drivers, nurses and orderlies of the SWH cared for badly injured soldiers and were stationed close to the front line. They often demonstrated bravery in the most trying of cirmcumstances—many worked whilst under fire and some SWH members even died in the course of their duties.[14]

Helga pictured as part of her SWH unit.

It appears Helga was involved with the SWH from its inception. In December 1914, she left for France as part of the French Hospital Unit. Her role was described as a ‘dresser’. However, once at Royamount Abbey, where the hospital was based, Helga worked as an ambulance driver, transporting injured men from the front line to the hospital. This was a particularly dangerous job, and she was often ‘in danger of being killed by shells.”[15] During one particularly fraught drive, “Between the line and the hospital her back wheels were shot away, her driving wheel was splintered between her hands.’[16]

In addition to this, essential medical tools were in short supply. In 1915 Helga wrote a letter to an NUWSS branch ’ sending greetings to the meeting and appealing for help, “the men were dying like flies from preventable causes.”[17] Helga was awarded a number of medals for her service, British War Medal, British Victory Medal, Croix de Guerre, and Medaille des Epidemies.

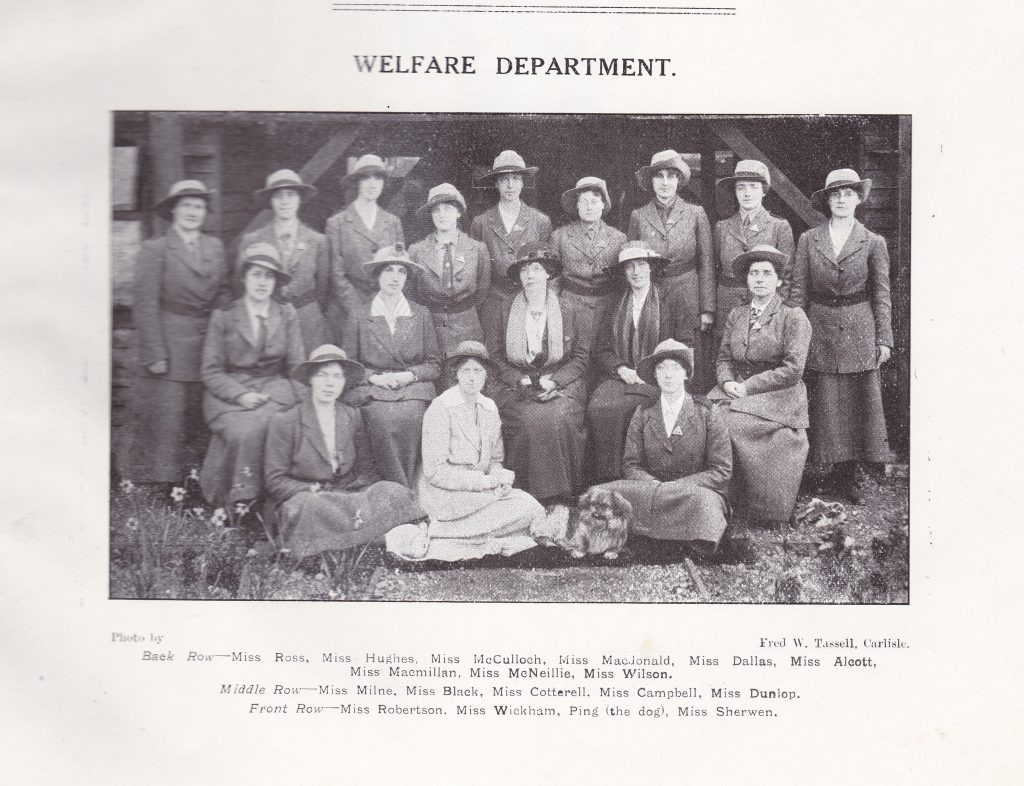

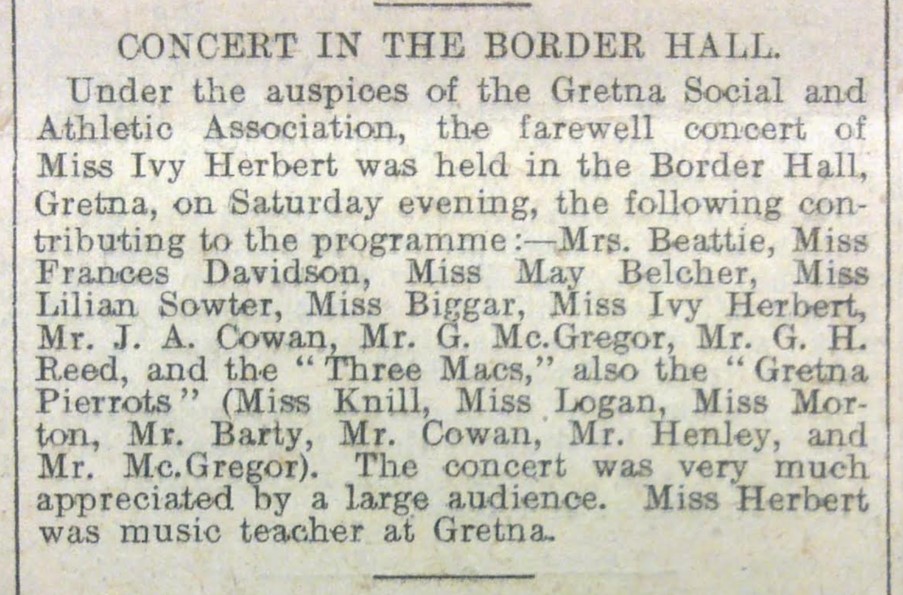

The stress of working so close to the front and in such a high pressure job had adverse effects on Helga’s heart, and so she came to work at HM Factory Gretna. As she is described in her obiturary as ‘mothering’ and ‘disciplining the girls’, I suspect she was part of the Welfare Department at the factory.

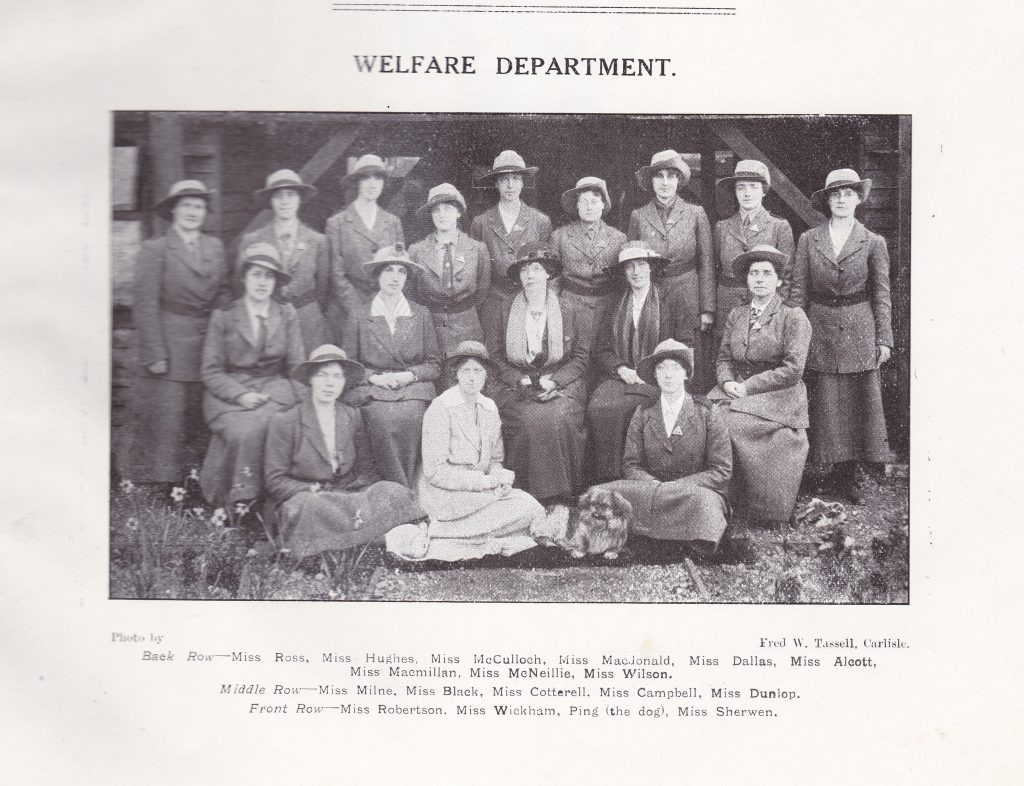

The Welfare Department, although Helga isn’t pictured

As described by our volunteer Virginia in her excellent article on welfare[18]:

“Lady superintendents were a vital part in the operations of a munition factory. Behind the factory walls, lady superintendents were the hidden cornerstones of support for female munition workers during the demands of the First World War. In maintaining the health and wellbeing of her workers, lady superintendents enabled factory production to continue and the demands of War to be efficiently met. Therefore, lady superintendents should be regarded as protecting the progress of munition factories during the First World War, as much as guardians of welfare.”

After the war ended, Helga adopted a child and became heavily involved in the Women’s Institute. However, her health was permanently affected from her war time service. Her death was sudden and tragic. She passed away after a car accident in 1928, aged only 43.

[1] The Women’s Leader, 30th November 1928, p. 7.

[2] https://map.mappingwomenssuffrage.org.uk/items/show/265

[3] Blom, I., 1980. The struggle for women’s suffrage in Norway, 1885–1913. Scandinavian Journal of History, 5(1-4), pp.3-22.

[4] Women’s Franchise, 6th February 1908, p. 6.

[5] Women’s Franchise, 13th February 1908, p. 6.; Votes for Women, 24th September 1908, p. 4.

[6] Women’s Franchise, 17th December 1908, p. 6.; Women’s Franchise, 24th December 1908, p. 6.

[7] Women’s Franchise, 24th December 1908, p. 6.

[8] https://map.mappingwomenssuffrage.org.uk/items/show/265

[9] https://map.mappingwomenssuffrage.org.uk/items/show/265

[10] For example see: Lisburn Standard, 3rd February 1912, p. 4.

[11] Common Cause, 9th May 1912, p. 8.

[12] Common Cause, 30th November 1928, p. 7.

[13] Common Cause, 7 December 1928. P. 2.

[14] Crofton, E., 2012. The women of Royaumont. Edinburgh: John Donald.

[15] Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 27th November 1915, p. 4.

[16] The Women’s Leader, 30th November 1928, p. 7.

[17] Common Cause 19th February 1915., p. 11.

[18] Guardians of Welfare: The Role of Female Superintendents in Munition Factories and their Contribution to Female Workers during the First World War – Devils Porridge Museum

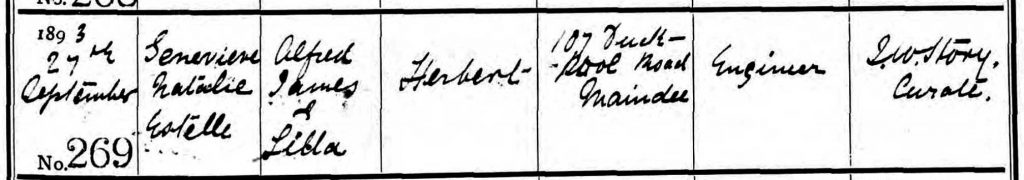

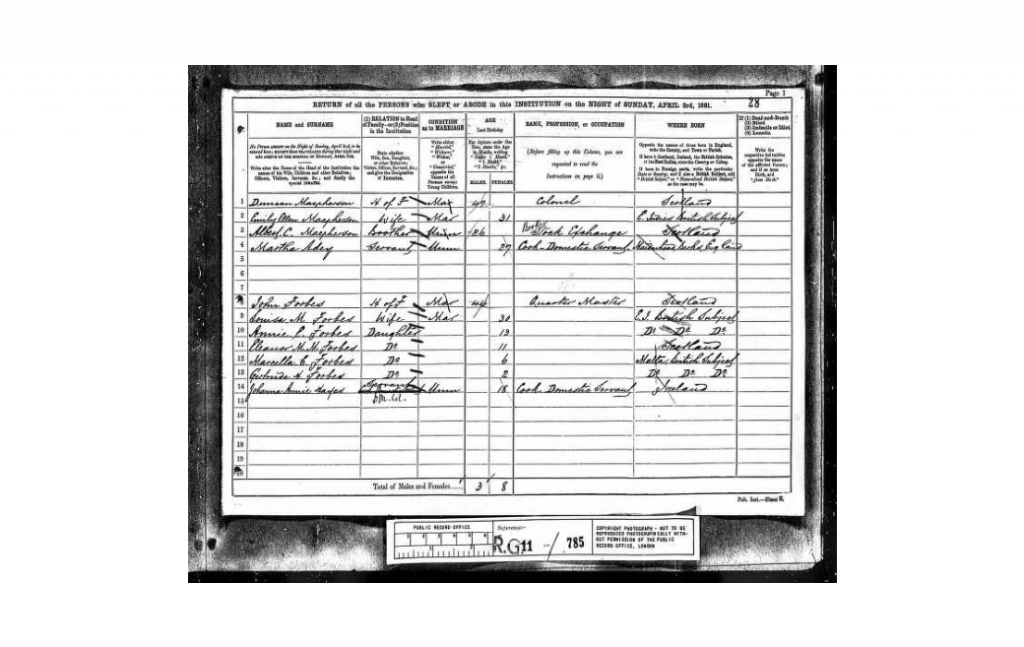

On return from Malta, the 1881 census has the family living at Aldershot Barracks, John’s role is Quartermaster. By 22nd November 1882 they were in Edinburgh when Henry Maurice was born at 21 Scotland Street ( birth registration )

On return from Malta, the 1881 census has the family living at Aldershot Barracks, John’s role is Quartermaster. By 22nd November 1882 they were in Edinburgh when Henry Maurice was born at 21 Scotland Street ( birth registration )