Written and researched by Stuart Gibbs

In 1994 an article by P L Scowcroft highlighting the knowledge gap of British women composers was published on Music Web. On figure highlighted by the article was Ivy Herbert, a composer from the early to mid 20th century. At her height was a prolific composer and performer making numerous stage and radio appearance, she was secretary to the Surrey County Music Committee and had a close connection to the prominent composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. Despite this little was known about Herbert with almost no biographical detail. However, the key to unlocking the mystery was Ivy Herbert’s connection to HM Gretna and a brief reference in a Carlisle newspaper.

Early life in Newport and Studying at the Royal Academy

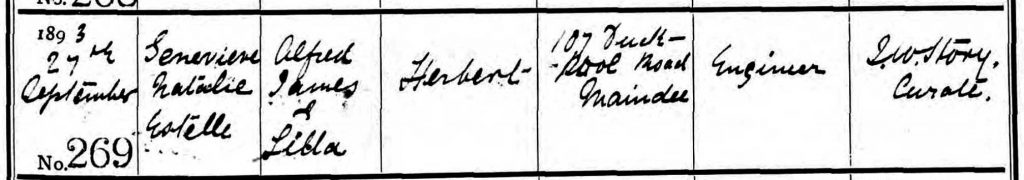

Ivy Herbert’s birth record christened in 1893 as Genevieve Natalie Estelle Herbert

Ivy Herbert was born on June 7th, 1893, in Newport, Wales, and christened as Genevieve Natalie Estelle Herbert. Her father Alfred was a ship’s engineer and Ivy spent her early years at 107 Duckpool Road. Music education was an important part of life in Newport, but Ivy also had natural talent inherited it seems from her mother’s side, Lilla Flint. The Flints of Northampton were rather musical and the Welsh branch of the family, were no different. Ivy however was something of a child prodigy with her proficiency on the keyboard earning her the nickname “Ivy”. In the 1901 census she is recorded as ‘Ivy GNE Herbert’ and she used the name ‘Ivy Herbert’ for the bulk of her career as a musician and composer.

Ivy Herbert picture taken from an article published in the Western Mail in 1928

The 1911 census records Ivy as a music student, and the January 1912 issue of Musical Times lists Ivy among the students that passed the Royal Academy of Music’s Metropolitan Exam held during December 1911. The Royal Academy of Music was founded in London in 1822, when Ivy attended in the late 1900s the institution had just moved to its present location on Marylebone Road. During her time there she specialised in Pianoforte and on June 27th, 1916, Ivy took part in a student’s concert at the Royal Academy her last it seems as a student. Within a few months Ivy was part of the war effort when she was employed as a music teacher at the massive cordite production centre at HM Gretna.

Acting as Music Tutor at HM Gretna and the Royal Academy

The Social and Recreation Committee at the Gretna factory was set up with the express purpose of providing activities for the workers and keeping them on site as much as possible. Among the social events organised by the Social Department was an Orchestral Society which was established to support the productions of the Choral and Operatic society. Ivy worked with the Orchestral Society holding classes in an upper floor room of the Gretna Institute which was often used as a classroom. Initially the orchestra was supplemented by professional musicians but as 1916 came to an end the need for outside help diminished and Ivy’s services were dispensed with in the early spring of 1917.

Gretna Institute where Ivy may have taught music during the later half of 1916 and the early months of 1917

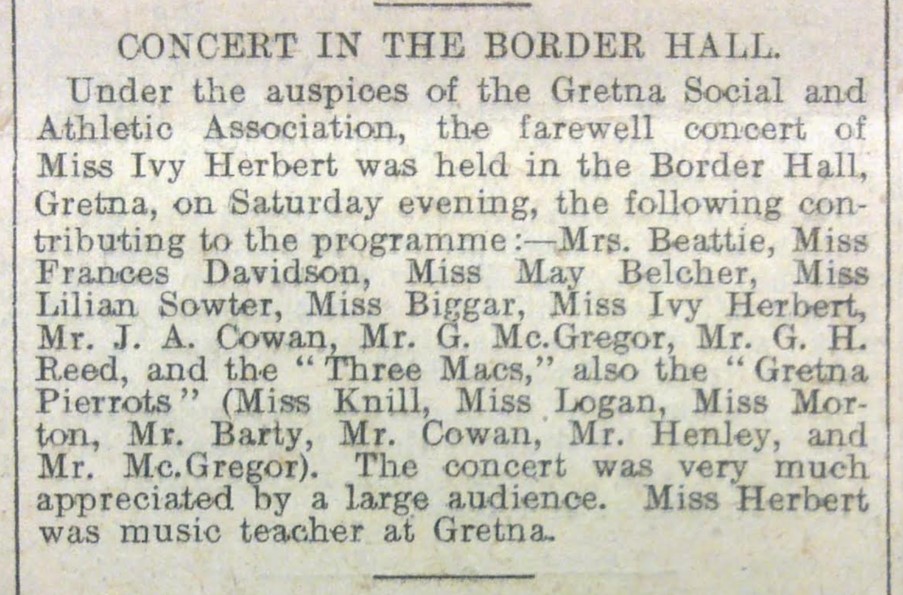

A farewell concert was organised for her at the Border Hall on Saturday March 10th, 1917. Ivy performed some of her music and star turns by the “Three Macs” and the “Gretna Pierrots” helped ensure a large audience. On leaving Gretna, Ivy returned to London residing at 20 Alexander Street, Bayswater and took up a position as tutor at the Royal Academy. During the summer of 1918 Six Miniatures for Piano, Ivy’s first published work, was issued. It is highly likely that pieces from this collection were written or even performed at HM Gretna. More work followed with Six Short Pieces for Piano in 1919 Danse de Piano in 1920 and Two Short Pieces for Piano in 1921. Ivy’s academic career at the Royal Academy also progressed and by 31 she was professor of pianoforte and bestowed the title Associate of the Royal Academy.

Ivy Herbert Carlisle Journal account of her farewell concert at the Border Hall in March 1917

On the Concert Circuit and in Radio Broadcasts

As a result, Ivy was in constant demand on the concert circuit. In 1928 she appeared in Cardiff with the newly formed National Orchestra of Wales. Conducted by Warwick Braithwaite Ivy gave the standout performance, a rendition of Nikolai Rimsky Korsakov’s Piano Concerto in C Sharp Minor. Besides live performances she also featured regularly on radio in concerts and recitals. She even had a weekly educational broadcast for schools which went out on the Cardiff channel. A particular highlight was a broadcast on the World Service in 1937 performing a series of short recitals which went out on All India Radio.

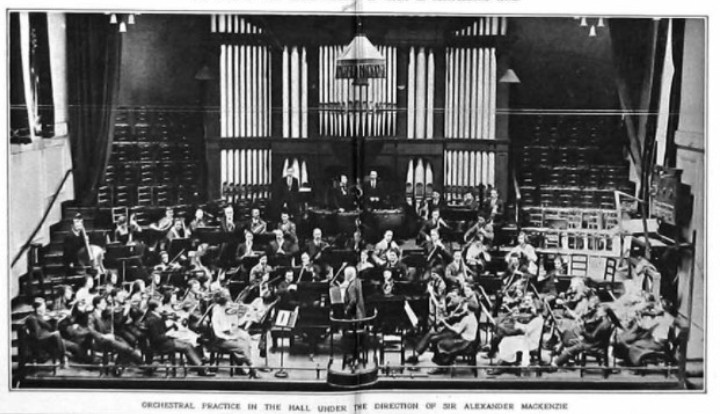

An Orchestra practice at the Royal Academy of Music during 1922 Ivy was a tutor at the college at this time

The 1930 Post Office directory still lists Ivy as living at 20 Alexander Street, also at this address is a ‘Miss Potto’. This was Florence Potto born in 1884 at Weeping Cross, Staffordshire. The daughter of Arthur Potto, a Police Inspector, she was brought up in the village of Great Heywood and by the late 1920s she had left village life behind to settle in London. Florence worked as welfare organiser and may also have acted as an ad hoc private secretary to deal with Ivy’s burgeoning diary, which included organising live and radio appearances as well as private tuition. For the next four decades Florence would be ever present.

The Outbreak of War Relocating to Dorking and working with Vaughan Williams

Ivy Herbert taking part in a CEMA organised concert in 1942

With Florence’s retirement in the late 1930s the decision was made to relocate to the suburbs, taking up residence in Dorking at Westcott Street. Ivy was quickly involved in the local music scene acting as the honorary secretary for the Surrey County Music Committee. Formed in late 1941 the body was chaired by the eminent composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams. He was brought up in Wotton during the 1870s and 80s. Owing to his wife Adeline chronic arthritis, Vaughan Williams had returned to the area in 1929 taking up residence at ‘The White Gates’ in Dorking.

Ivy was also involved with the Council for the Encouragement of Music and Arts (CEMA). With the outbreak of a new conflict in 1939 the need to try and preserve cultural life was recognised with CEMA being established in January 1940. The body was chaired by the prominent economist John Maynard Keynes with the aim of ‘bringing art to the masses’ by organising arts events and concerts within the community. Ivy was involved in numerous CEMA events and even made a brief appearance in a promotional film for the body released in 1942. One CEMA organised event was held close to Ivy’s Westcott home at the Abinger Village Hall in May 1942. The event attracted a good turn out with Ralph Vaughan Williams amongst the audience. On January 31st, 1943, Ivy was back at Abinger Village Hall along with Margery Cullen, secretary of the Leith Hill Music Festival. They were performing a practice run of Vaughan William’s Fifth Symphony on two pianos while Vaughan Williams busily took notes. The Fifth Symphony had its first orchestral performance at the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios on May 25th, 1943, and Ivy was among the invited guests attending the session.

In a raid over Bayswater on October 7th, 1940, several bombs landed on Newton Road, close to Ivy and Florence’s former home at Alexander Street but by 1943 the war increasingly moved to the suburbs. In January 1944 Westcott was bombed with four houses on the Watson Road destroyed, killing a total of nine people. Then on February 24th a Dornier was brought down on Parsonage Lane close to Fir Crest Cottage. Two of the crew managed to bail out and were arrested in nearby Wotton. As a result, Ivy Herbert and Florence Potto moved into Vaughan William’s residence ‘The White Gate’ staying in one a room set out for them. In the early spring of 1944 Dorking was hit by a new menace the V1. On June 19th, 1944, this crude version

of today’s drone landed on the Elm Cottage on Sandy Lane close to ‘The White Gates’, killing two women and a boy. A few days later a V1 landed on Ockley causing a local woman to later die from shock. On August 3rd, 1944, another V 1 came down in Abinger Common, close to where the Fifth Symphony was rehearsed, destroying a local church.

The Immediate Post War and Later Life

Ivy Herbert and Florence Potto remained at ‘The White Gates’ until 1946 when they relocated to 16 Church Street in Dorking. Ivy went back to composing, providing music to the words of Robert Bridges for The Linnet Song and A Window Bird Sat Mourning by Percy Bysshe Shelley. These were published in 1947. While researchers have failed to uncover Ivy Herbert’s background, Florence Potto, also tried to research her own family history with the same level of success. She told the press that, ‘she had searched in vain for years for other Pottos. It must be one of the most uncommon of English names’. This changed when a Douglas Chapman of Witham, discovered scratched on a window of his shop, ‘Jane Potto July 7, 1776’, and contacted the Daily Herald newspaper. In April 1954 Florence along with ten other members of the Potto ‘clan’ were invited to Witham to witness Mr Chapman’s example of 18th Century graffiti.

By the 1950s Ivy Herbert was less active on the concert circuit and her last recorded work was in 1949. CEMA became the Arts Council and with the new body and new chair -Maynard Keynes died in 1946 – many of the opportunities Ivy had previously received dried up. She returned to the Academy to sit an LARAM exam (Licentiate of the Royal Academy of Music) and poured her energies into teaching. Ivy and Florence resided in Dorking for the next twenty years. Florence Potto died in the early months of 1969 while Ivy Herbert, remained at 16 Church Street until the mid 1970s. She spent her remaining years in Bromley where she died on November 4th, 1993, a few months after her 100th birthday; little notice was taken of her passing.

As with other art forms women composers have been excluded from general music history and their work is often missing from ‘the standard concert repertoire’. This process has been intrenched at academic level with the use of standardized references which emphasize the composers and genres considered most relevant and are not designed to be inclusive. But there is some good news for the would-be researcher, the apparent amnesia regarding women’s history is a contemporary phenomenon and what Ivy Herbert’s story shows us is that with the appropriate due diligence, these ‘lost histories’ can be readily recovered.