Worker of the Week is a weekly blogpost series which will highlight one of the workers at H.M. Gretna our volunteers have researched for The Miracle Workers Project. This is an exciting project that aims to centralise all of the 30,000 people who worked at Gretna during World War One. If you want to find out more, or if you’d like to get involved in the project, please email laura@devilsporridge.org.uk. This week, Marilyn tells us about her research into Alice May Sherwen.

Alice May was the middle child of Peter (1843 -1895) and Sarah Ann nee Walker (1855-1936). Peter, a Yeoman farmer “ of an old Gosforth Yeoman family” ( local press 1895) farmed at High Boonwood , Gosforth, Cumberland. Sarah was from Eaglesfield near Cockermouth, also of farming stock. The 1861 census tells us that Sarah’s father was aged 40, a farmer of 67 acres employing 2 men and 1 woman. On the other hand, in the same year, Peter was a farmer’s son of 60 acres. By 1871 both farmers had increased their acreage. Peter married Sarah, 12 years his junior, at St Bees on 18th October 1882 although in which establishment is unknown. Sarah was from a Quaker family( Society of Friends) but there is no evidence to suggest that this was a Quaker wedding. Marriage relieved Sarah of being the housekeeper for her brother Isaac ( 1881 census).

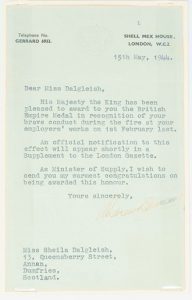

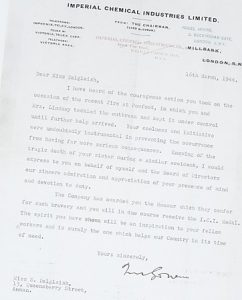

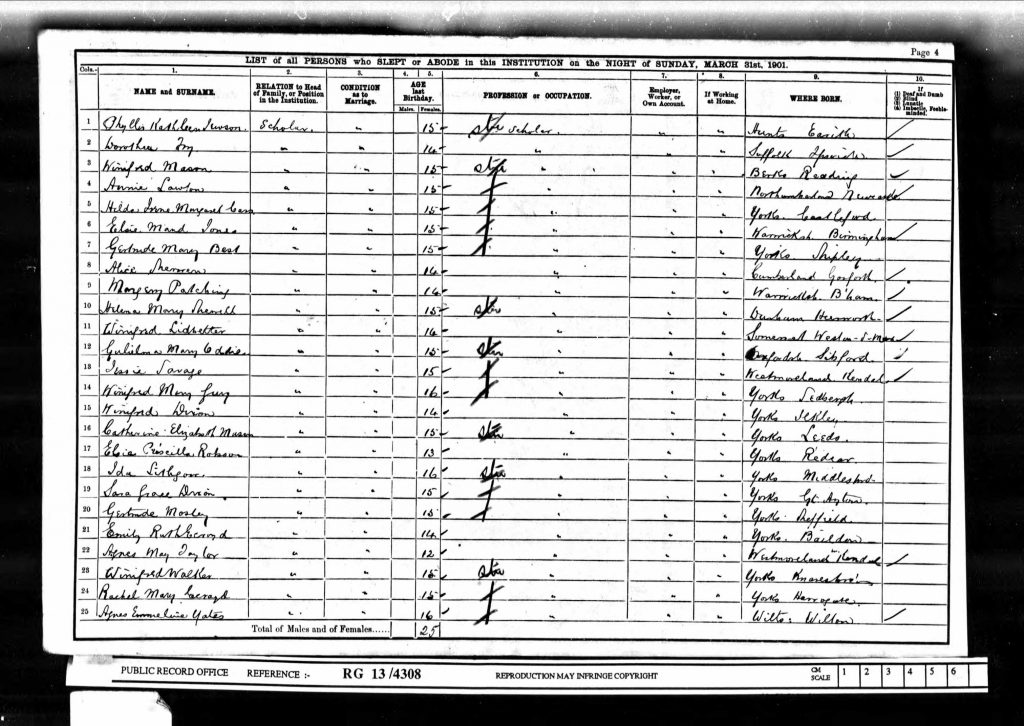

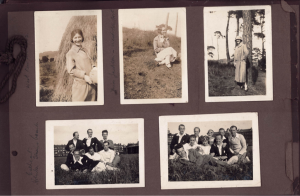

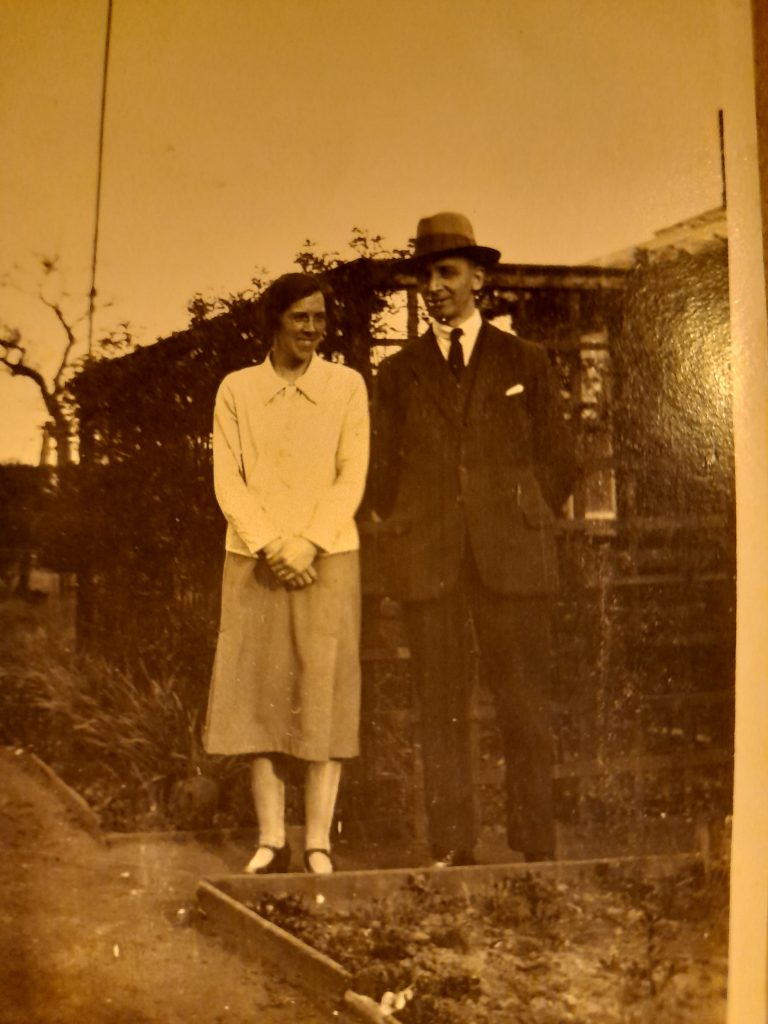

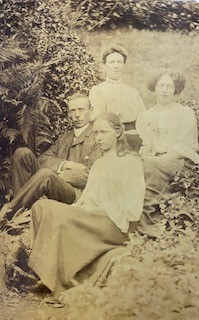

The Sherwen family — Alice is pictured along with her sister, brother and mother. Photo Credit: Whitehaven Archives

In the autumn of 1883, a son ,Henry, was born, followed by Alice May in January 1887 and Helena Mary on Christmas Eve 1889.

The children took pleasure in their local landscape, High Boonwood, enjoying panoramic views of Wasdale and Scafell Pike as well as out to the Irish Sea. The Maryport Advertiser of Saturday 29th July, 1893 reported :-

“ YOUTHFUL MOUNTAINEERS On Saturday, Henry, Alice M and Helena M Sherwen of Gosforth, Cumberland , aged respectively nine, seven, three years and seven months, climbed to the highest point of Scawfell, the two former without assistance. The ascent was made from Wasdale Head.”

There is

A photograph of the three young Sherwens leaning over into a lake with a behatted lady holding a fishing rod in one hand and hanging onto the youngest child ( Helena) with the other. Photo credit: Whitehaven Archives

Just two years later in 1895 when Henry was a boarder at Brookfield, The Quaker School, Wigton, their father died of stomach cancer ( Whitehaven Archive- death certificate and a letter form Henry at Brookfield to his mother) The death was reported in the local press. He apparently had taken a keen interest in church matter, having served as church warden, and was a regular attender at vestry meetings. He was 53.

At only 40 with three young children, 12, 8 and 6, records in local papers of the time show that Sarah let High Boonwood in 1897.

By 1901 Mrs S Sherwen is listed in Bulmers Directory of West Cumberland as proprietor of “ Gowrie”, Apartments, Eskdale. Advertisements in West Cumberland Times of June 1893 showed that these apartments were” let furnished, 5 minutes walk from the station ( Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway), uninterrupted view from the rooms.”

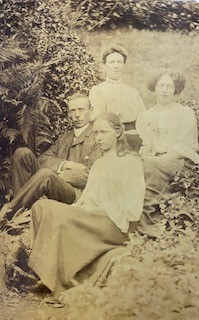

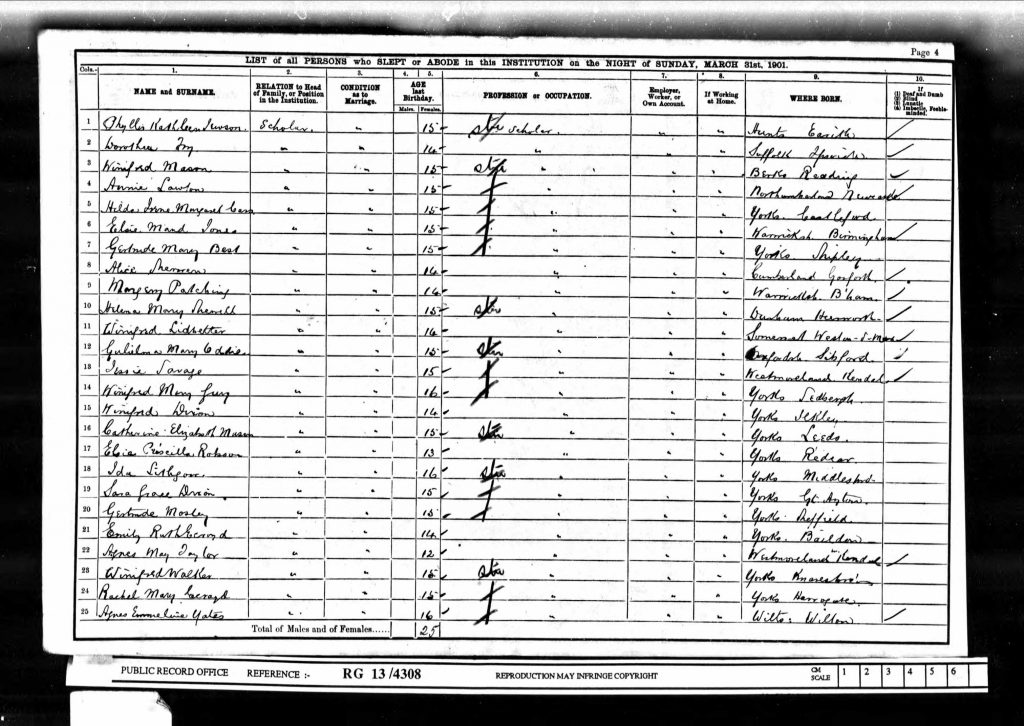

Alice is noted as a scholar in the 1901 census

This is the year that the census lists Alice , aged 14 , at Ackworth School (a Quaker establishment) near Pontefract, as a boarder. A letter from her headmaster dated 23rd November 1901 informs us that Alice has been unsuccessful in gaining an apprenticeship and suggests she would “ do better as a teacher in a private family despite “many points in her character” ( Whitehaven Archives)

There is an indication that this was as Alice left Ackworth and moved to The Mount, an all girls Quaker school in York. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph of Monday 27th February 1905 listed the successful candidates at matriculation for the University of London including Alice M Sherwen, The Mount School.

Her final report from The Mount school, held by Whitehaven Archives, shows that she had been teaching in the junior department , probably as a pupil teacher. Most of her studies were of aspects of education including theory. The comment on the practical:-

“ Her work shows a marked improvement. Lessons carefully prepared and give evidence of much interest in subject matter and in teaching. Has nor yet enough sympathy with children, nor reached that point of contact without which a good lesson cannot be given.

Discipline-Fair”

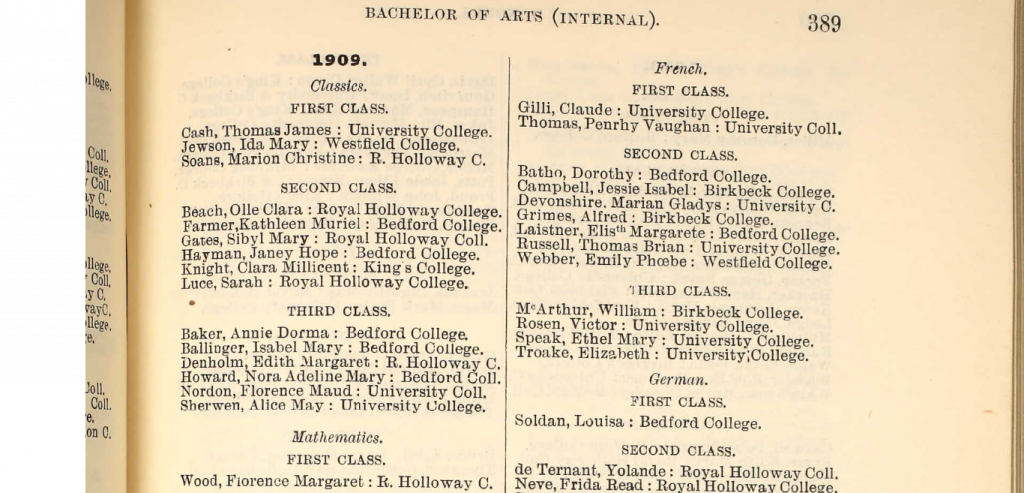

In 1906, Alice started her studies in Classics at the University of London.

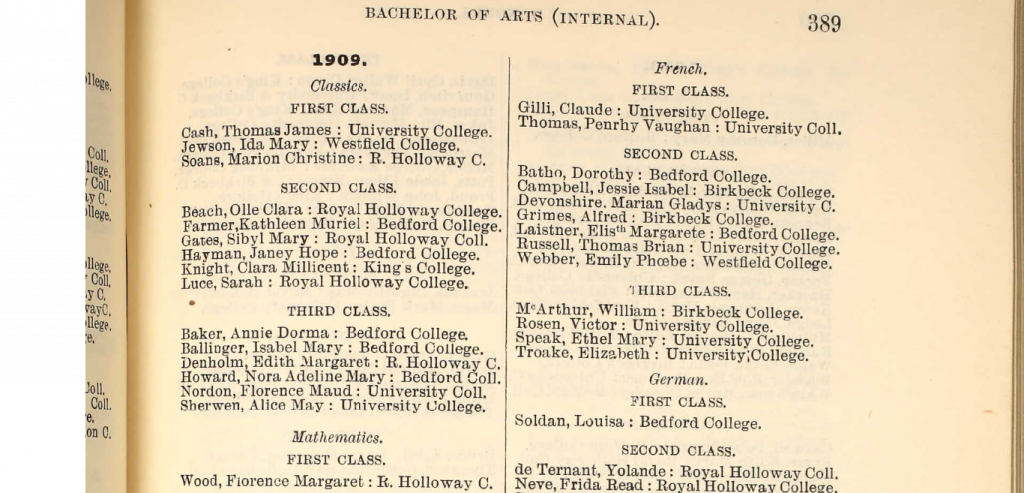

Alice was awarded a third class degree in classics in 1909

We know that Alice graduated from University College, London University with a 3rd class degree in Classics as listed in the University register of graduates for 1909.

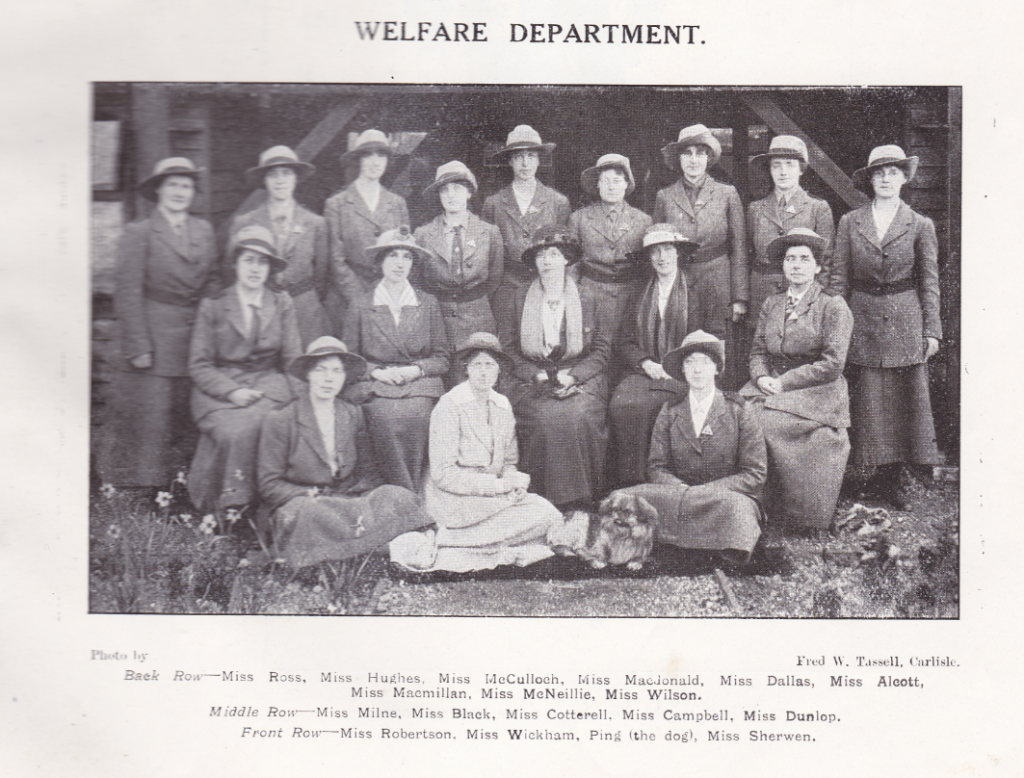

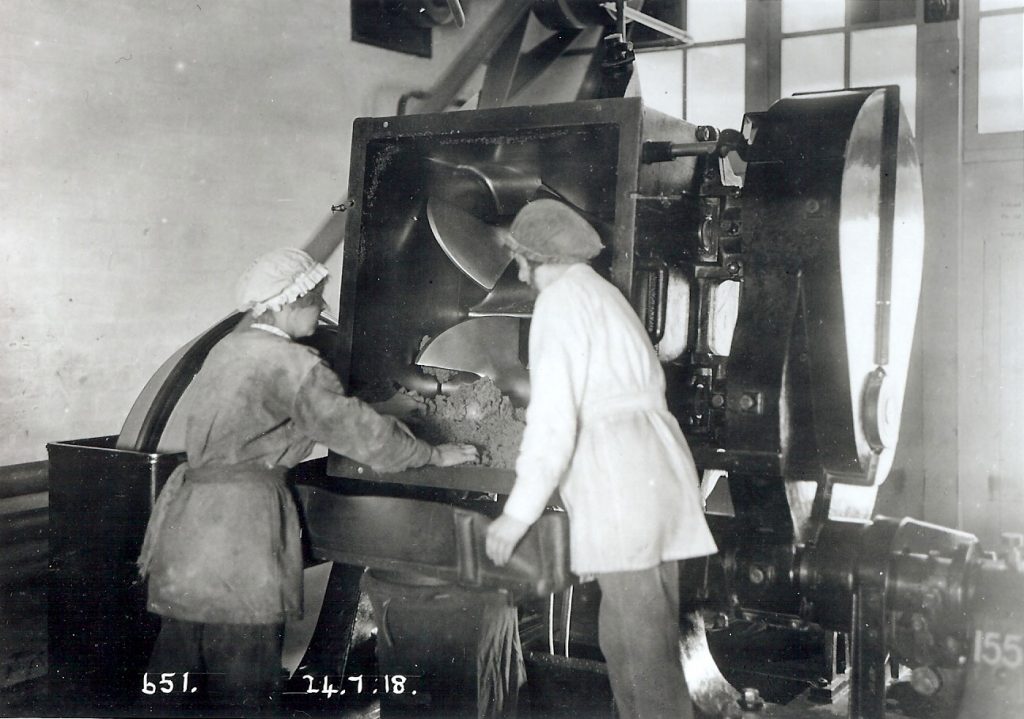

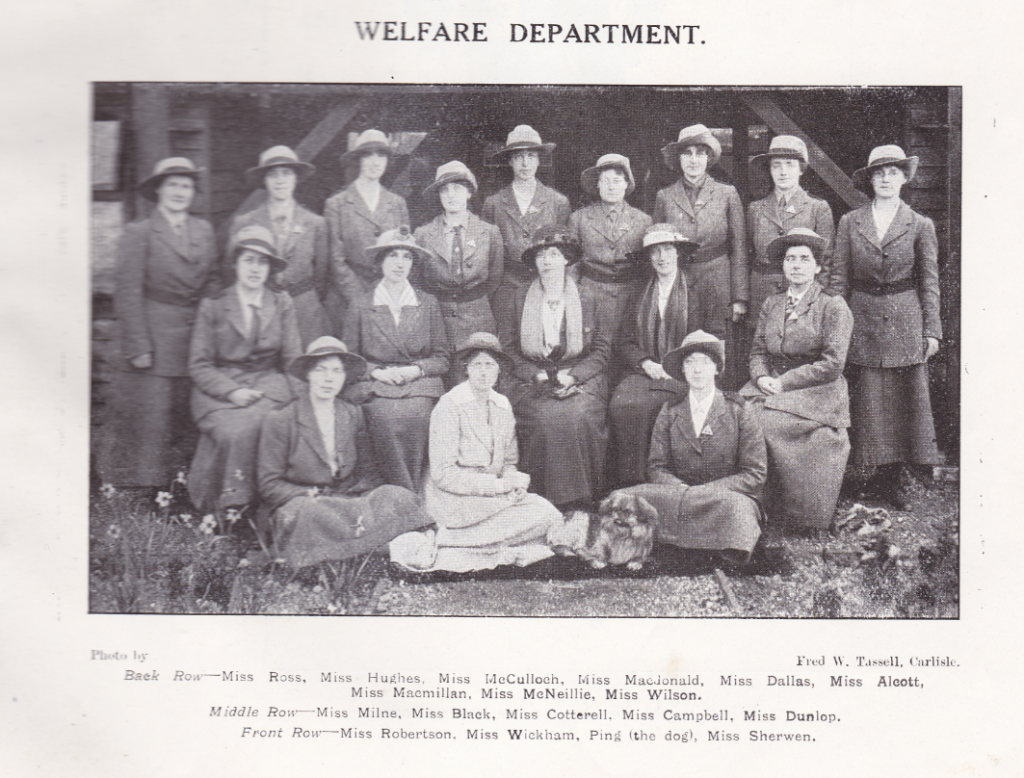

Alice pictured alongside her fellow welfare workers in the Mossband Farewell.

Alice is pictured in the Mossband Farewell, sitting on the front row beside “Ping” the dog amongst the Welfare Department staff. Her address is listed under “ Supervisors” This role was created by Lloyd George specifically for Munitions initially when the State became a huge employer of thousands of young women.

Welfare Supervisors came from backgrounds such as teaching , nursing and social care . Alice would have been 29 in 1916 and we know from evidence that she was a teacher despite what her headmaster had written about her.

There is no indication as to where Alice lived whilst working at H M Factory Gretna nor what her sister did during the war years.

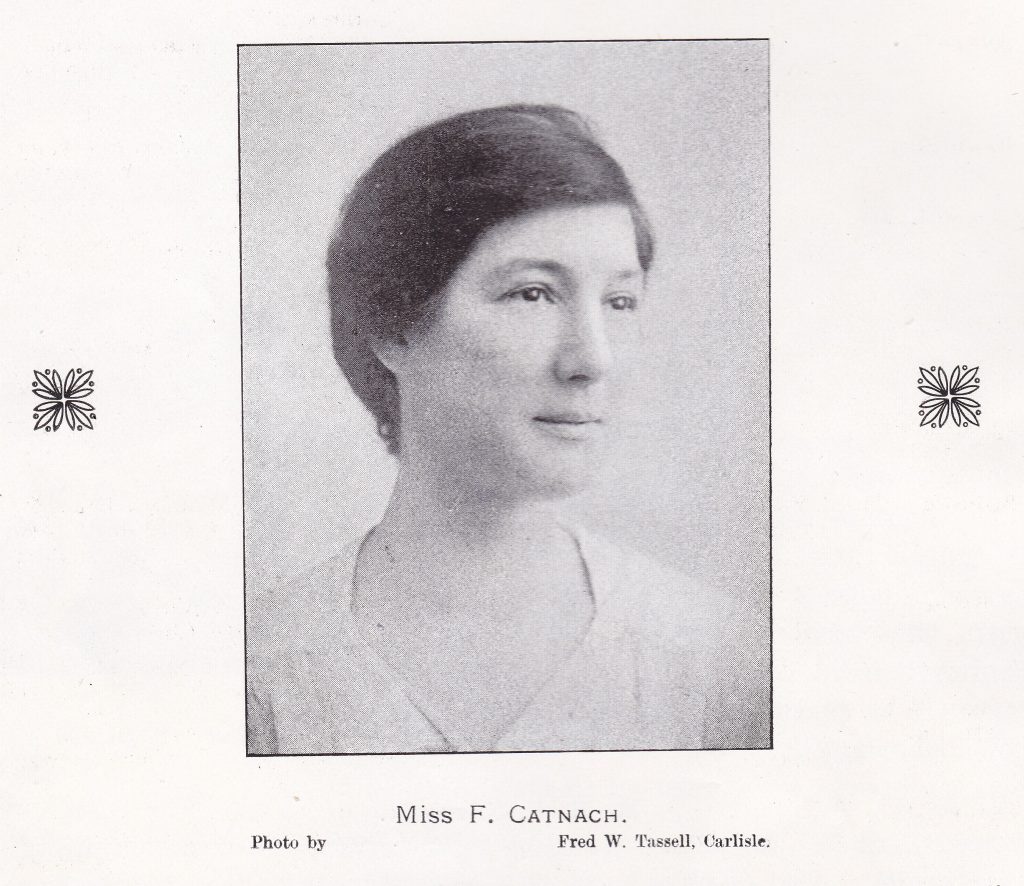

Alice May Sherwen. Photo credit: Whitehaven Archives

The next mention of Alice is in the Whitehaven Archives in a letter dated 30th August 1920 from the Unity School of Christianity. The Unity Church, founded in 1889, is a spiritual movement that indoctrinates positivity. The movement is largely based in America, and the letter is from Missouri. The letter assures Miss Sherwen ‘of our continued prayers for you and your friend’.

This is quite a move from her Quaker upbringing. Could it have been the War and working at HM Factory Gretna that urged her to seek a different denomination?

Alice was teaching at The English School Cairo from at least January 1920 to new year 1921. The letters held by Whitehaven Archives are revealing. Usually addressed to “Dear mother , H +H” starting monthly and about 8 pages long moving through a period in May as shorter weekly missives.

January 14th 1920 “ The Headmaster is a capable, bumptious, little man without any of the qualities of a man in his positions should have except those of a head of business.”

May 1920 following the killing of several Englishmen –“ Killing Englishmen is a sort of sport with the natives.”

Also in May she is very taken with Lord Allenby – “ a striking figure” following a reception at Lord and Lady Allenby’s residence’

During the school summer break she travels to Greece and in July writes “ You will be sorry ( or glad) to hear that I have changed so much -I no longer think Boonwood road a bad road!”

Some of her letter begin to be sent to friends at this point . She talks about medical and science lectures and exhibitions.

She also mentions that she suffers from neuralgia and that the New Year ( 1921) is going to be very eventful for mum and Henry.

Her brother Henry married Annie Wilson in Whitehaven in the spring of 1921 and they had a daughter Joan on 28th September 1922.

Whitehaven Archives hold a bundle of inward letters from Arthur Dadford, soldier in Palestine (13th Pack Battery, Jerusalem), to Alice Sherwen, who was in Cairo at the time.

“The letters addressed to ‘English School’ suggest her travelling for a teaching position, one sample listing in [Arabic?] marked ‘private!!’ and two photographs possibly of Dadford. The first letter, dated on the 6 Oct 1921, says it was four days since Alice left Jerusalem which would have been the 2 Oct. The letters are romantic, but also detail his background and army life in Jerusalem. He briefly mentions resentment towards Germans (29 Nov 1921, p. 6.) The letters in this bundle end with notice of Dadford leaving the service on 14 Sep 1922.”

In 1923 a letter from The Association of Assistant Mistresses is sent to “ Birk Howe “, Eskdale. This is several properties down from “ Gowrie” but another fine property overlooking the valley. This is the house where her mother died in 1936, Alice being named in the Probate record.

She sailed to Cape Town, 1st class onboard the “ Durham Castle” on 3rd January 1924, accompanied by another teacher, Miss S B Robinson. Their address was 11 Winsford House W 1. This could have been the address of a teaching agency. She returned , 3rd Class on 24th March 1925. Her intended address being 8 Cavendish Gardens, W1.

Whitehaven Archives hold a catalogue belonging to Alice from the Universal Astrological Service indicating horoscopes, distance learning and much more. They also hold a journal in which Alice has written almost daily extracts from reading material , mainly philosophical and though provoking. One such extract relates the position of racism in society.

Further into the book it seems Alice has had some sort of “ reading” with a clairvoyant or similar and has written down what was said:-April 1924 Mrs Winson “ – someone has broken your heart. The rest of the year will be good one.” The writing refers to Ena Mary ( Helena) “ helping you to take the right step”

It continues:- “ If you had married him he would have dragged you down until it might possibly have ended in S D ( you have meditated on this in the past.)

Referring to possible marriage “ They would not have allowed it.” Could this have been Arthur Dadford?

Whitehaven Archives hold a telegram to Miss Alice Sherwen from The Joint Agency For Women Teachers, 21st December 1925 “ COMMISSION 3% OF SALARY OF £75 15 0”

At some point Alice tried her hand at novel writing, 5 hand written unpublished novels are held in the Archives. She wrote under the pseudonym, Alice Rivers. The themes of some are religious. They are entitled: The Mother, The Spirit of the Four Raps, Exiles, The Gateway of Life and Dawn.

The 1930 electoral register for London places both sisters in London- Alice at 19 Gordon Street , Camden and Helena lodging at 39 Portman Square. Helena was still there in 1931. Alice was settled in Gordon St until at least 1936 but at number 5 in that year when her address is listed for passengers departing on 22nd December Madeira arriving Southampton on 4th January 1937.

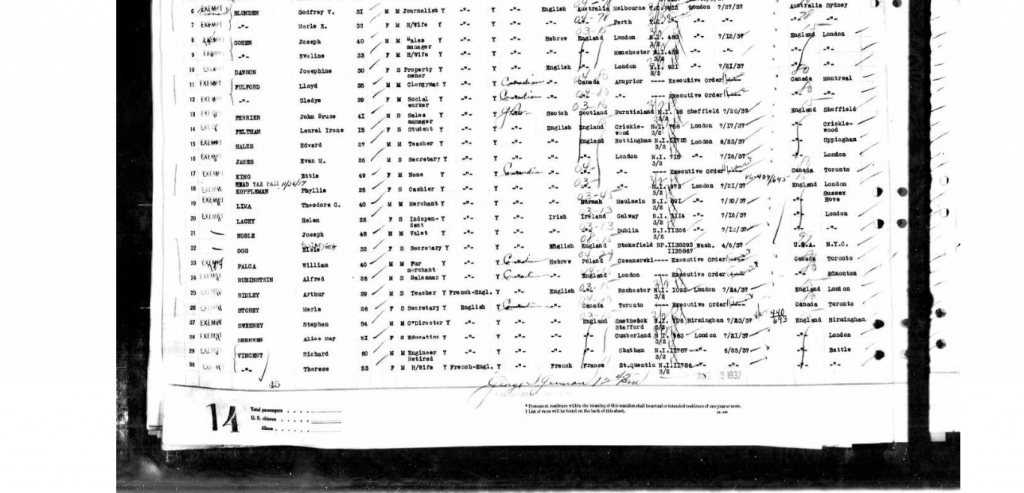

Alice was an experienced traveller by this point in her life– in 1937 she visited New York.

By 1936, their niece Joan born in 1922, had followed the family tradition and been educated at Ackworth Quaker School, nr Pontefract . She is listed there aged 17 on the 1939 register but in 1936 travelled seemingly alone to Mombasa, Kenya as a student. Later Passenger listings show that she travelled and stayed for long periods in Mombasa with her husband and young children.

Sarah, their mother died in 1936 and Alice May was named in the Probate register.

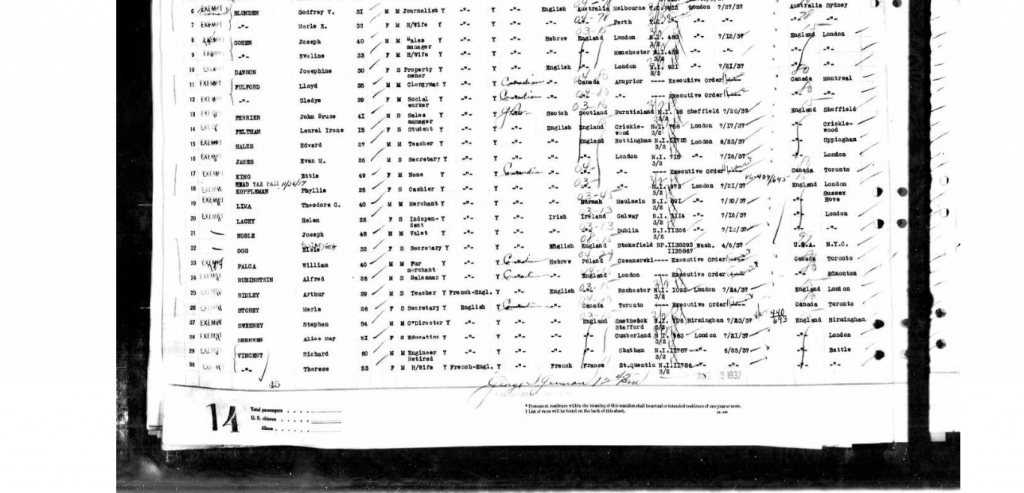

Having arrived back in England in January 1937, Alice travelled from Southampton to New York City in July arriving on 2nd August . She gave her home address as 5 Gordon Gardens, London and is heading to C/O National Bible Institute, 340W , 55 Street, NYC and intended to stay for less than 60 days. The most fascinating insight from this passenger list is that we now learn that aged 50 , Alice has grey hair, blue eyes , fair complexion and is 5’ 5” tall. Interestingly she gives her nearest relative as a cousin , Mr Herbert Walker -possibly he was the nearest geographically rather than relatively.

She arrived back on 13th September on board the Queen Mary.

Alice does not seem to appear on the 1939 register – perhaps she was on one of her many trips abroad some of which are indicated on postcards sent to her from her travels and held in the Whitehaven Records.

Helena does appear on the 1939 register , living at 8 College Precincts, Worcester, single and a teacher for the blind.

We know from electoral registers that Alice stayed in London moving from Camberwell in 1947 to Peckham -1949. She was living at 3 Elmhurst Villas, Cheltenham Road London SE15 from at least 1951 to her death in 1967 aged 80.

The probate register – “SHERWEN Alice May of 3 Elmhurst Villas, Cheltenham Road, London S.E.15 who was last seen alive on 14th April 1967 and whose dead body was found on 15th April 1967. Administration London 26th September to Helena Mary Sherwen spinster. £13341

The final chapter for Alice is the cremation record accessed via deceased online . Her cremation took place at Honor Oak Crematorium, Southwark. The record included in the attached folder shows that her ashes were scattered in The Spinney. In an address book in the Whitehaven Archive, written in very shaky pencil handwriting is an address for Alice at Honor Dale School, Peckham Rye, London SE22. It is not clear whether this book belonged to Alice’s mother or sister. Most probably to Helena.

…and finally for Helena who ended her days at Wythop View, Embleton, nr Cockermouth. She died in 1974 and is buried in the Quaker burial ground at Pardshaw , probably alongside her maternal grandparents.

The Sherwen family. Photo credit: Whitehaven Archives