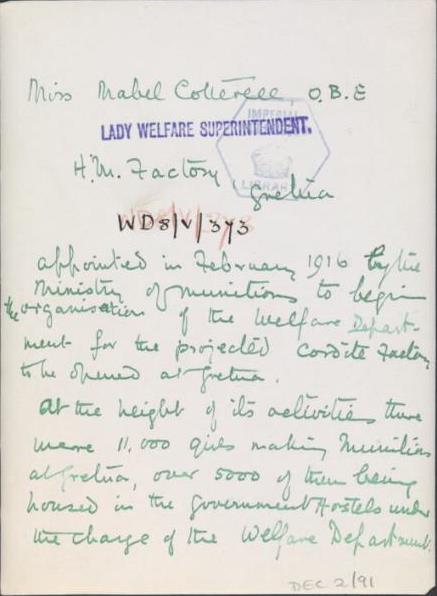

The Miracle Workers Research Project began in 2021, with research volunteers striving to find out more about the 30,000 people who worked at HM Factory Gretna in World War One. In the months since, many fascinating and previously unknown histories have been uncovered. Today, volunteer Virginia writes about her research into lady superintendents.

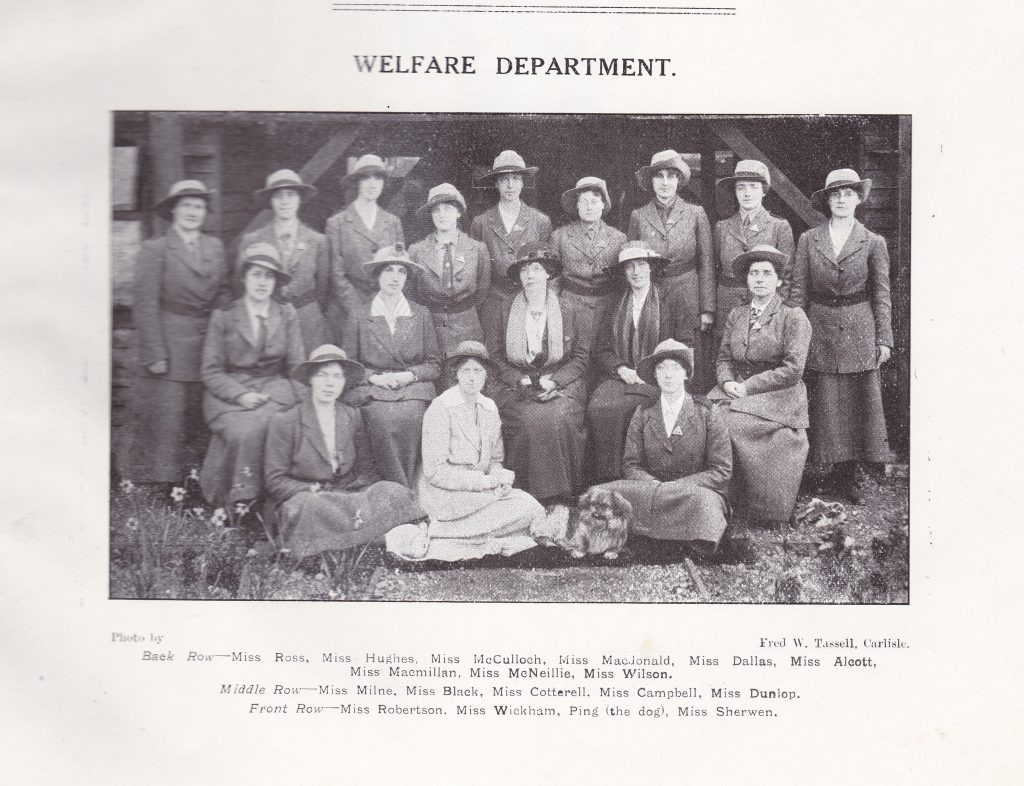

The origins of lady superintendents in munition factories originated in mid-1915.[1] As the production of shells increased during this period, the Ministry of Munition needed to maintain the welfare of female munition workers.[2] The role of the lady superintendents, also referred to as Welfare Supervisors, was to, therefore, care for female factory workers.[3] The blog explores the diverse qualities and duties of female superintendents in munition factories during the First World War. Their many responsibilities were vital to guaranteeing the health and wellbeing of munition workers and consequently supporting the War effort.

Qualities of Lady Superintendents in munition factories during the First World War

Maintaining welfare in a munition factory required lady superintendents to possess and reflect various qualities to address the different needs of individual workers. They also had to understand and effectively respond to the demands and challenges munition factories posed.

In his book, ‘The Woman’s Part: A Record of Munitions Work’, from 1918, L.K. Yates referred to lady superintendents as ‘capable.’[4] Yates suggests that they had to be skilful and effective when addressing the needs and enquiries of their female workers. To do this required lady superintendents to be adaptable towards each female worker.

The need to be astute also applies to lady superintendents in munition factories. They had to assess situations and implement suitable responses to maintain the welfare of female workers, whilst maintaining efficiency in the factory. In the ‘Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’, employers in Britain’s munition factories praise the efficiency of lady superintendents towards work problems.[5] Lady superintendents were valued by their employees and munition factory operatives deemed their work essential in enabling the factory to run.

Another quality that applied to the role of lady superintendents was authoritativeness. To protect workers from the dangers of working in a munition factory, they had to uphold order and discipline amongst female workers. Under her supervision, workers did not become distracted or disorderly, which supported their safety and further enabled efficiency in meeting production demands.

As Welfare Supervisors, lady superintendents had to be dependable for female workers requiring her help. They also had to be reliable in effectively addressing the needs and concerns of workers. Due to this, lady superintendents were given a great responsibility in being a constant source of support and comfort for female munition workers during the War.

Roles of Lady Superintendents during the First World War

Guardians of Welfare

From their establishment in 1915, the main role of lady superintendents was to ensure the welfare of female munition workers. Within this duty, they were responsible for inspecting restrooms so that they met health standards.[6] Lady superintendents also inspected workrooms to maintain a healthy working environment.[7] They would report poor ventilation and uncleanness, for example, to the manager for correction.[8]

Lady superintendents were also responsible for providing healthy living conditions for factory workers.[9] If a lady superintendents deemed these unsuitable, she had the authority to inform the factory manager.[10] Aside from maintaining the health and wellbeing of female workers in the factory, these responsibilities infiltrated into the private lives of female workers. This reflects the extensive lengths lady superintendents went to in order to protect their workers.

Due to the limited availability of the factory manager to regularly inspect the factory, lady superintendents were crucial in preventing health risks in the factory. They also advised the factory manager on the physical health of individual workers.[11] In outlining dangers to the factory manager and providing information on the health of workers, lady superintendents reflected their duty of care towards female workers. However, this also enabled factory production to meet demands.

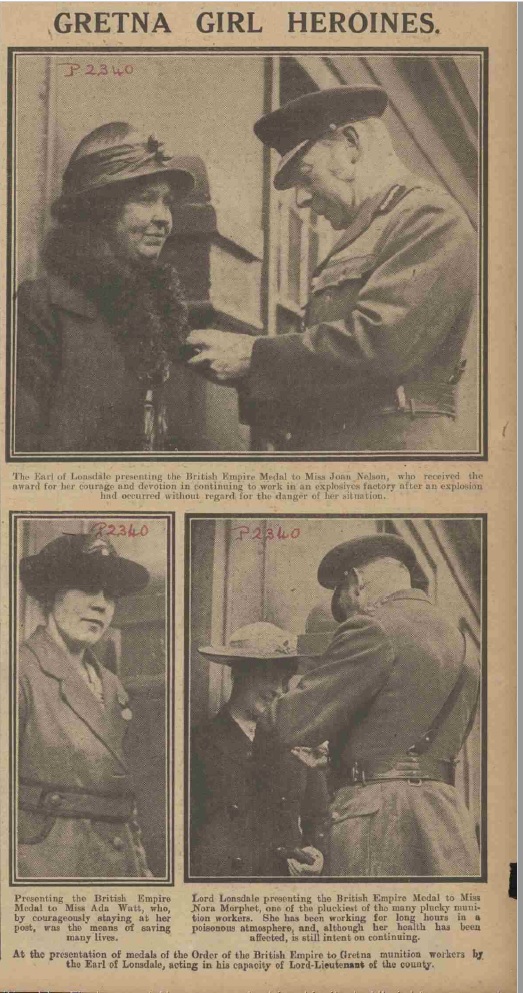

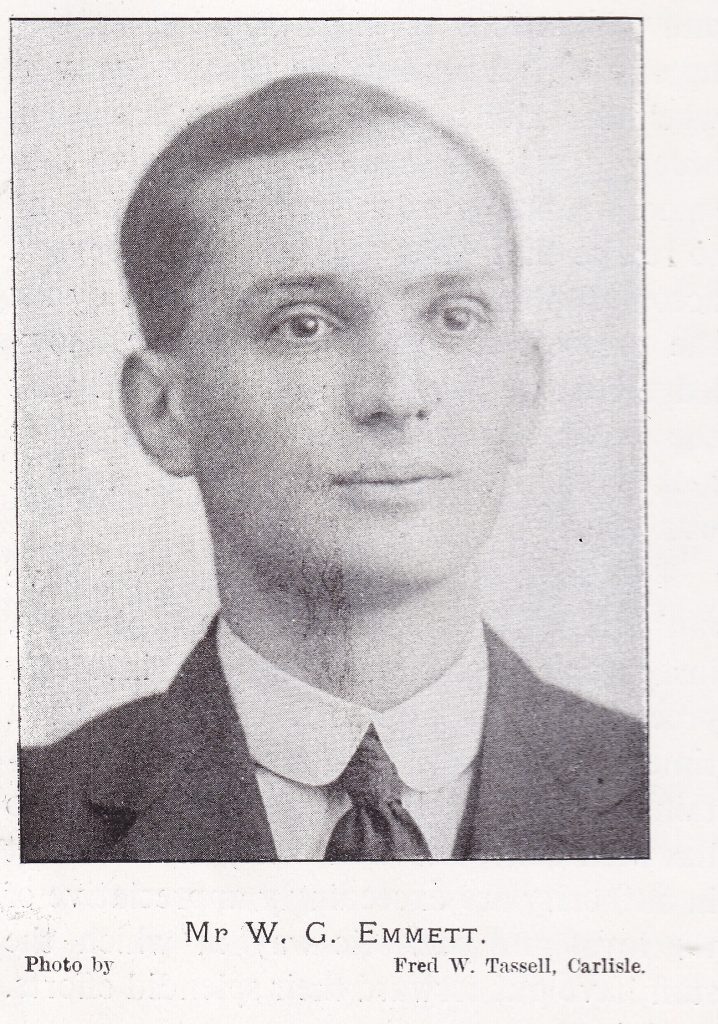

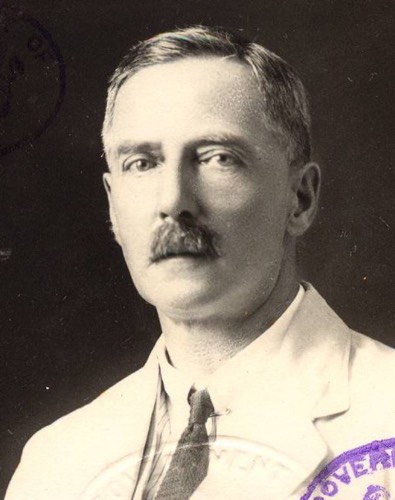

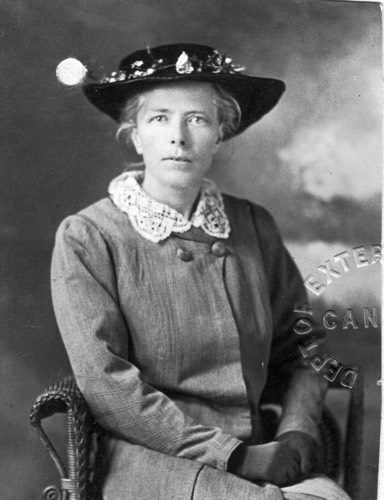

Dame Lilian Barker was a prominent Lady Superintendent at Woolwich Arsenal and oversaw 30,000 female workers.[12] Lilian knew all of her female workers individually, enabling her to respond to their personal needs.[13] In 1944, she received a DBE for her “services in connection with the welfare of women and girl.’’[14] Her DBE signifies the extents she went to and significant impact she had, in ensuring the health and wellbeing of her female workers.

Chief Lady Superintendent Miss Lilian Barker CBE, Woolwich Arsenal. Courtesy of Imperial War Museums. © IWM WWC D8-4-158. [15]

Other welfare issues addressed to factory managers concerned the suitability of work for female workers.[16] Lady superintendents observed women’s work in the munition factory and reported work they deemed unfit for workers.[17] In doing so, lady superintendents incorporated their astuteness to provide their duty of care for female workers and maintain their health.

Lady superintendents also had medical responsibilities including curing illnesses, cooperating with nurses and doctors alongside managing first aid.[18] According to the U.S. Department of Labor Statistics in 1918, they also had the ability to make long term positive changes to women’s health. For example, they could offer appropriate diets and exercises for women.[19] They were also expected to identify fatigue in workers and advise women on how to preserve energy, such as changing their posture.[20] Through their advice, lady Superintendents further helped to maintain the health and efficiency of factories.

Addressing complaints was another responsibility of lady superintendents which contributed to the welfare of workers. Alongside knowing the wages of all workers, they had to report complaints, including wages to the manager.[21] For the female workers, lady superintendents provided a voice for their concerns within the factory. Lady superintendents, therefore, helped to relieve anxiety and stress amongst workers, reducing discontent in the factory.[22]

Through these various responsibilities, lady superintendents sought to prevent mistreatment of female workers and ensure them that she was the guardians of their welfare.[23]

Domestic responsibilities

To further support their provision of welfare, lady superintendents managed catering so that factory workers were well nourished.[24] They also guaranteed a supply of workwear, including overalls and shoes, further enabling the factory to run efficiently.[25]

A significant responsibility of female superintendents was supervising night shifts.[26] Not only did they provide continued protection for workers during the night, but her supervision prevented disorderly behaviour, which threatened production.

Moral and Social Responsibilities

In 1917, an employer of a munition factory in Britain stated:

‘’Generally speaking, we consider it very essential to have a lady superintendent where female workers are employed, and especially where there are men working in the same department.’’[27]

The need to have a lady superintendent amongst a male and female workforce strengthens the guardianship role of Lady Superintendents towards female munition workers. The munition manager implies how crucial lady superintendents were in instilling discipline amongst workers and in preventing distractions at work.

Whilst lady superintendents maintained morality in their female workers, they were also important in boosting morale for their female workers during the First World War.[28] Lady superintendents were to reflect positivity towards female munition workers and make sure that women understood the significance of their work during the War.[29]

Similarly to ensuring suitable living conditions for female workers, they visited female workers outside of the home.[30] Their visits emphasise how their duty of care and protection towards female workers extended beyond the munition factory. Visiting homes of workers also enabled lady superintendents to further understand the personal lives of their workers enabling them to effectively respond to their needs.

Lady superintendents also played an important role in the lives of their workers outside the factory by providing recreational activities.[31] Recreational clubs were created by lady superintendents, allowing female munition workers to rest and socialise outside the factory.[32]

Dorothée Aurélie Marianne Pullinger was a Lady Superintendent who catered for workers beyond the munition factory. During the First World War, Dorothee worked at the munition factory under the Vickers engineering company.[33] Overseeing 7000 female workers, she established an apprenticeship scheme for female munition workers.[34] Dorothee’s apprenticeships show that alongside the welfare of workers, she invested in the progression and welfare of her workers even after the War.

Lady superintendents were a vital part in the operations of a munition factory. Behind the factory walls, lady superintendents were the hidden cornerstones of support for female munition workers during the demands of the First World War. In maintaining the health and wellbeing of her workers, lady superintendents enabled factory production to continue and the demands of War to be efficiently met. Therefore, lady superintendents should be regarded as protecting the progress of munition factories during the First World War, as much as guardians of welfare.

By Virginia Quigley

Bibliography

Carr, Jessica, Women’s Work in Munitions Factories during The First World War: Gender, Class and Public Opinion (Northumbria, 2016)

Yates, L.K., The Woman’s Part: A Record of Munitions Work (Alexandria, 1918)

Health of Munition Workers, Great Britain, ‘Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’

Vol. 2, No. 5 (1916), pp. 66-70

U.S. Department of Labor United States Training Service C.T. Clayton, Industrial Training for Foundry Workers, Training Bulletin No. 24 (Washington, 1919)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lilian_Barker

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205379875

U.S. Department of Labor Statistics, Proceedings of the Employment Managers’ Conference, Rochester, N.Y., May 9, 10, 11, 1918. January, 1919

Great Britain. Ministry of Munitions. Health of Munition Workers Committee. Welfare Work in British Munition Factories: Reprints of the Memoranda of the British Health of Munition Workers Committee

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doroth%C3%A9e_Pullinger

[1] Jessica Carr, Women’s Work in Munitions Factories during The First World War: Gender, Class and Public Opinion (Northumbria, 2016), p. 14.

[2] Ibid., p. 14.

[3] Ibid., p. 14.

[4] L.K. Yates, The Woman’s Part: A Record of Munitions Work (Alexandria, 1918), p. 60.

[5] Health of Munition Workers, Great Britain, ‘Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’

Vol. 2, No. 5 (1916), p. 68.

[6] U.S. Department of Labor United States Training Service C.T. Clayton, Industrial Training for Foundry Workers, Training Bulletin No. 24 (Washington, 1919), p. 38.

[7] Ibid., p. 38.

[8] Ibid., p. 38.

[9] Ibid., p. 38.

[10] Ibid., p. 38.

[11] Ibid., p. 38.

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lilian_Barker (accessed: 19/08/2021)

[13] Carr, Women’s Work, p. 14.

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lilian_Barker (accessed: 19/08/2021)

[15] https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205379875, accessed: 25/08/2021

[16] Ibid., p. 38.

[17] Ibid., p. 38.

[18] Ibid, p. 39.

[19] U.S. Department of Labor Statistics, Proceedings of the Employment Managers’ Conference, Rochester, N.Y., May 9, 10, 11, 1918. January, 1919 (Washington, 1919), p. 14.

[20] Ibid., p. 14.

[21] Bulletin, p. 38.

[22] Ibid., p. 38.

[23] Ibid., p. 37.

[24] Great Britain. Ministry of Munitions. Health of Munition Workers Committee. Welfare Work in British Munition Factories: Reprints of the Memoranda of the British Health of Munition Workers Committee (Washington, 1917), p. 25.

[25] Bulletin, p 38.

[26] Ibid, p. 39.

[27] Ministry of Munitions, Welfare Work, p. 25.

[28] Bulletin, p. 37.

[29] Ibid., p. 37.

[30] Carr, Women’s Work, p. 14.

[31] Ibid., p. 39.

[32] Ibid., p. 39.

[33] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doroth%C3%A9e_Pullinger, (accessed: 19/08/2021)

[34] Ibid

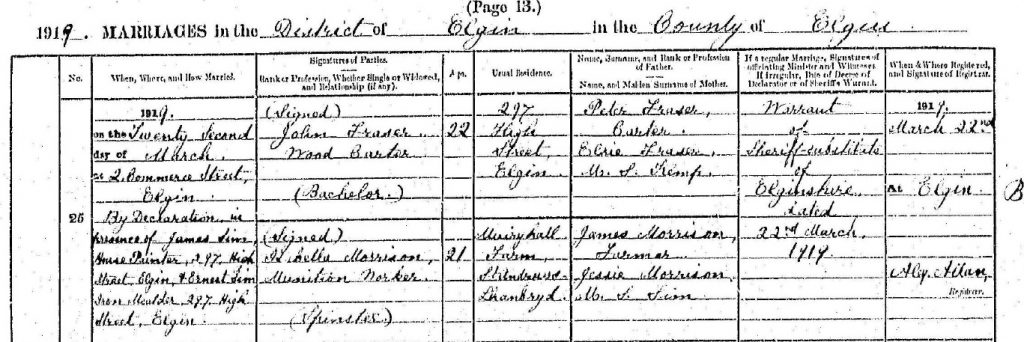

On 23

On 23