In the World Wars of the twentieth century, there are certain historical themes and people that almost everyone knows: Kaiser Wilhelm, Winston Churchill, young idealistic men hardened by their time at The Front, soldier-poets, VADs, The Blitz—the list goes on and on. These ideas, people and events are discussed and taught in almost every history classroom across the country. Like Henry VIII and his six wives, the World Wars are an integral part of our country’s collective history. Every year, on Remembrance Sunday, we pause and commemorate those who sacrificed so much and the men and women who lost their youths, and sometimes lives, to war. Although the story of both World Wars is well-trod, there are still discoveries to be made, and histories to be told. This article strives to be one of those.

This is the story of a woman who you’ve probably never heard of. I hadn’t either, till I started working at The Devil’s Porridge Museum in Eastriggs, Scotland. Maud Bruce was an ordinary woman who was extraordinarily courageous in the service of her country during both the 1914-1918 and the 1939-1945 wars. She is barely, if at all, mentioned in the numerous history books that cover both periods of history. Until a few months ago, she didn’t even have a Wikipedia entry. If you googled ‘Maud Bruce’ the first couple of entries would be all about a very different Maud Bruce—Robert the Bruce’s daughter, who lived in the 12th century! Our Maud Bruce is absent from history, and I am determined to put her back into it. Maud was a woman from a working-class background, traditionally not someone considered ‘important’ enough to be remembered. But Maud is important—she played a key role in munitions making in both wars, winning awards for her bravery.

This is the story of a woman who you’ve probably never heard of. I hadn’t either, till I started working at The Devil’s Porridge Museum in Eastriggs, Scotland. Maud Bruce was an ordinary woman who was extraordinarily courageous in the service of her country during both the 1914-1918 and the 1939-1945 wars. She is barely, if at all, mentioned in the numerous history books that cover both periods of history. Until a few months ago, she didn’t even have a Wikipedia entry. If you googled ‘Maud Bruce’ the first couple of entries would be all about a very different Maud Bruce—Robert the Bruce’s daughter, who lived in the 12th century! Our Maud Bruce is absent from history, and I am determined to put her back into it. Maud was a woman from a working-class background, traditionally not someone considered ‘important’ enough to be remembered. But Maud is important—she played a key role in munitions making in both wars, winning awards for her bravery.

Maud Ellen Bruce was born on 20th December 1894 in Coundon, Durham, England to Thomas and Emma Bruce. She was their fifth child and had two brothers and six sisters. Her father Thomas worked as a coalminer.[1] Coundon was traditionally a coalmining village, and Thomas probably worked at either Black Boy Colliery or Auckland Park Colliery, both nearby.

In 1901, Maud was six years old. Although the census doesn’t record whether or not she attended school, by this time education was compulsory by law for children aged five to twelve.[2] By 1911, Maud was sixteen and working as a general domestic servant.[3] Her older sister, Rose, who worked as a dressmaker, filled out the census form. This strongly implies that the Bruce children did have some form of education—they were clearly literate. Despite this, it is also clear that the family did require their older children to work to supplement the family income. Alongside Maud and Rose, William, then aged twenty-five, worked as a collier mechanic labourer and Emma, aged fourteen, was working nearby as a servant for James Black.[4]

Maud dressed in her munitions uniform

Prior to the World War One, the Gretna area was mostly agricultural, but during hostilities ‘the largest cordite factory in the UK was established’ in response to the need for munitions.[5] This new wartime industry meant a dramatic increase in the local population as people migrated to the area to work. One of these workers was Maud Bruce. Maud arrived at HM Gretna in late 1916 to work as a forewoman of the cotton drying house in the Dornock section. Maud was billeted at Grenville Hostel, Eastriggs.[6] She was head of the Women’s Fire Brigade and in charge of thirty girls. It is clear that Maud was an exemplary worker: she is described as having ‘gained rapid promotion’ during her time at Gretna, and as being ‘exceedingly popular’ with her staff and superiors.[7] It is likely that her younger sister, Lily also worked at the factory, as she appears in a photo alongside other munition workers in Maud’s papers.

Maud would have been doing potentially dangerous work in the factory—there were accidents throughout the war, and some munitions workers were horribly injured. Cordite was what was made at Gretna—a type of explosive propellent which went inside the shells used at the Front.

Maud was recognised for two notable events during her time at Gretna. The first occurred around April 1917, when a fire broke out at night in the cotton drying machine. Maud used a hose to subdue the flames, and then the fire brigade put out the fire.[8]

On the second occasion, Maud similarly demonstrated her calm and collected approach to danger. This event was outlined in detail in the local newspaper:

“Three months ago, about eight o’clock in the morning, she was close at hand when fire broke out in the drying machine. In a few seconds, the chamber was filled with smoke. As quick as lightning Miss Bruce climbed up the ladder to the top of the machine, twenty feet height, and with the vigorous use of a sweeping brush cut away the cotton at the top part of the machine, and pushed it down. In this way she prevented the fire spreading to the next machine. The staff of girls under her charge, encouraged by her example of coolness, set to work with the hose, and in a short time the fire, which was arrested in the willower part of the machine, and before it could reach the elevators, was successfully extinguished.”

In June 1917, Maud was awarded a British Empire Medal by The Duke of Buccleuch, K.T., who was Lord Lieutenant of the county of Dumfries.[9] This event was held at the central offices of the factory in front of a number of staff. It was stated that ‘each of the recipients of the medal stepped forward, and was cordially shaken hands with by the Duke, who pinned on the medals, and as he did so there were cordial cheers from the assembly.’[10] The Duke said that ‘it was extremely gratifying to realise that deeds of heroism were also being performed by factory workers at home, and especially by women.’[11]

Maud was awarded the Medal of the Order of the British Empire[12] (MOBE) in August 1917 ‘for admirable behaviour in charge of the women’s fire brigade at a fire at an explosive factory.’[13] In the aftermath of her heroic deeds, Maud had been interviewed by The Standard. She is described as wearing ‘khaki trousers and jacket’ and didn’t realise that she’d been awarded the MOBE at the time of the interview.[14]

Maud did get some media attention from her actions and the honours bestowed upon her. Usually these took the form of celebrating the work of women war workers. In the Sheffield Weekly Telegraph, she was referred to as a ‘plucky munitions lass’ and is cast as a heroine—the news story details the ‘thrilling story’ that led to her being awarded the Munitions Medal which it’s stated ‘has rarely been more pluckily won.’[15]

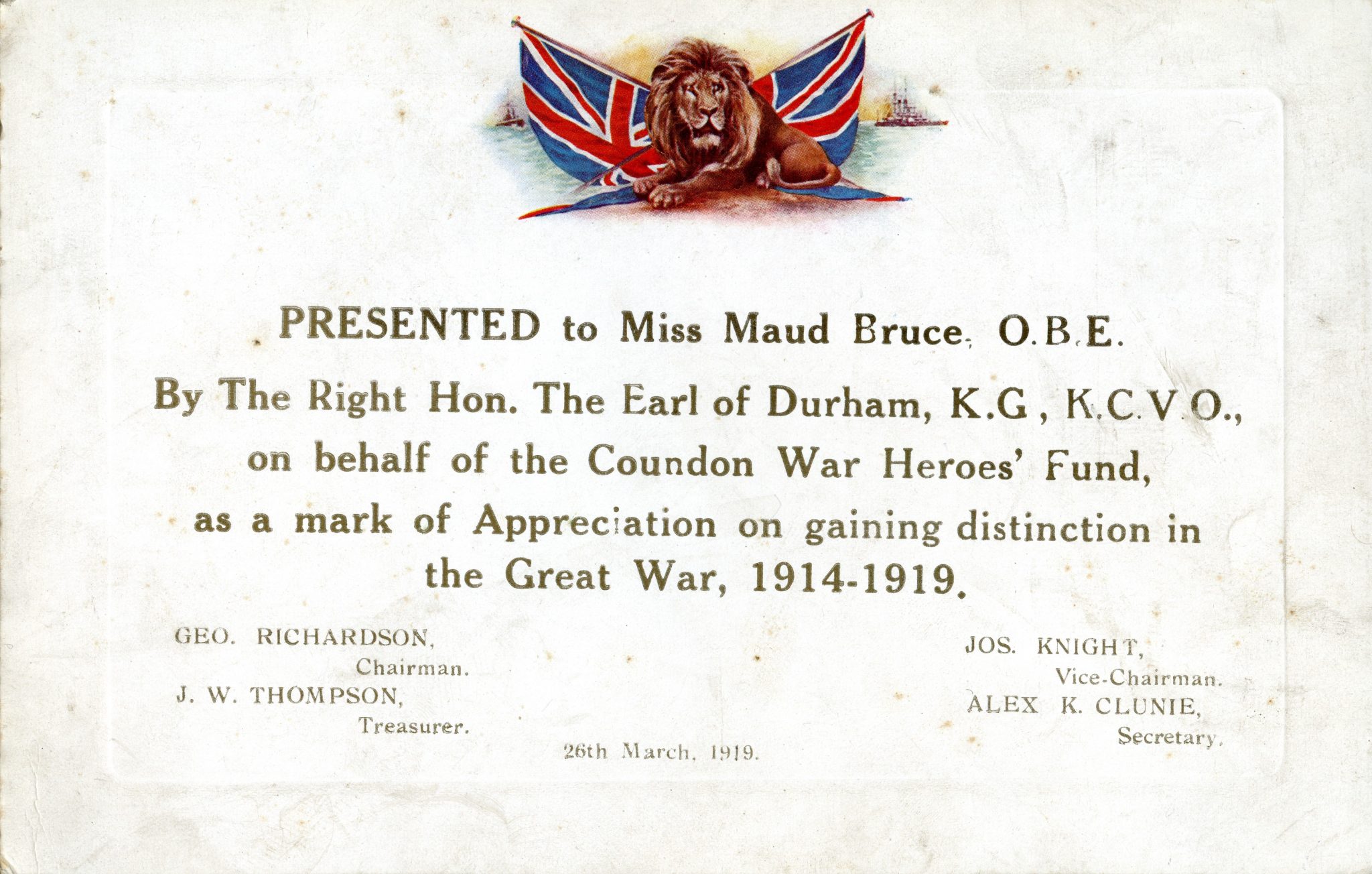

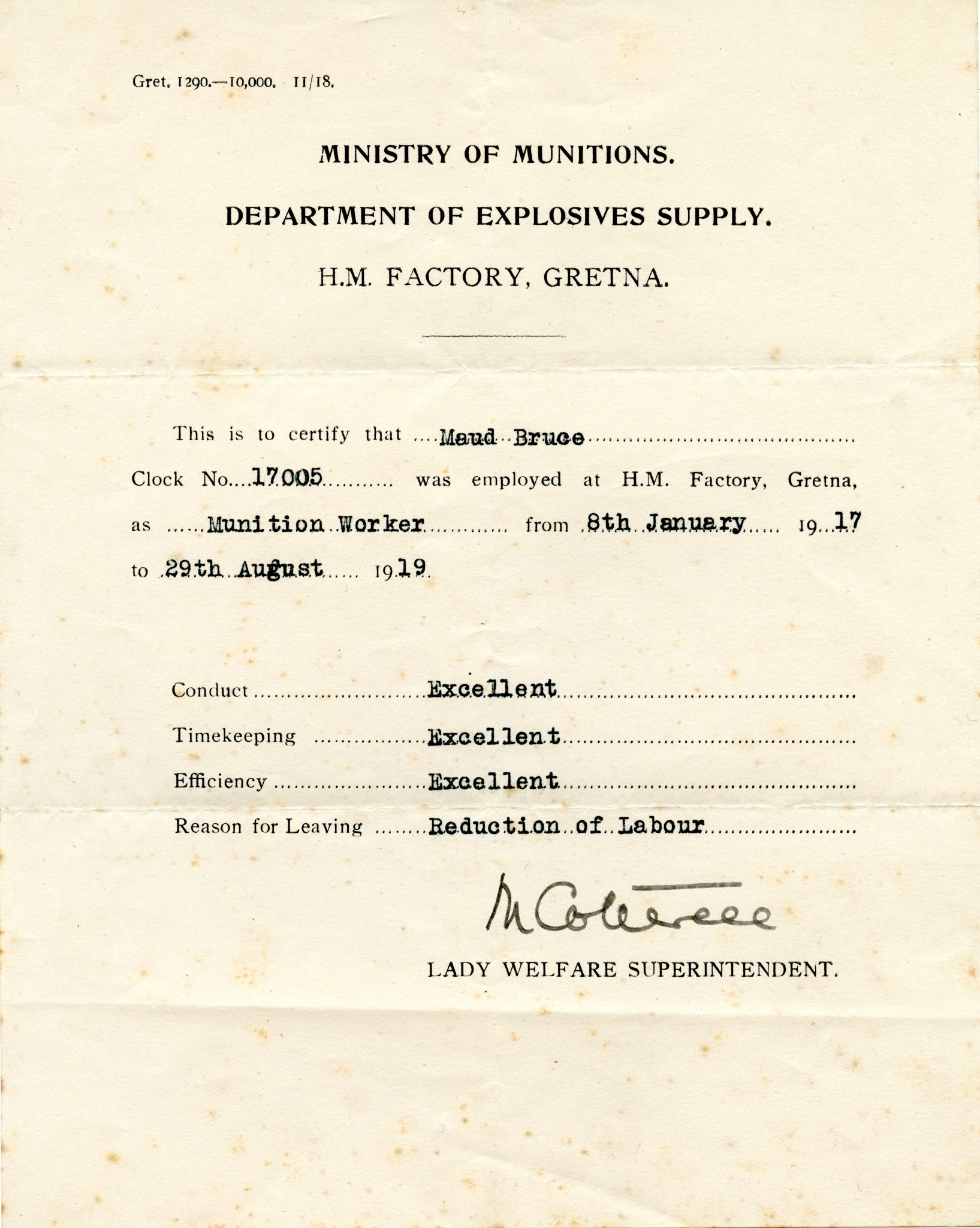

Maud worked at H. M. Factory Gretna from January 1917 – August 1919 and was only let go due to reduction of labour.

Maud worked at H. M. Factory Gretna from January 1917 – August 1919 and was only let go due to reduction of labour.

The year after leaving Gretna, Maud married Thomas Edward Nunn in Shildon, Durham, England.[16] Thomas had grown up in Shildon, only around 4 miles from Maud’s hometown of Coundon.[17] He was born on July 8th 1892, and was the son of Charles Nunn, a coalminer and Ellen Nunn. He had a younger sister, Lily and a younger half-brother, Wilfred. Aged 19, in 1911, Thomas had followed in his father’s footsteps and was working as a banking out miner.[18] Like Maud, Thomas had played his part in the war effort. He served in the Royal Irish Regiment and was discharged due to disability on 10th May 1917.[19] Thomas received the Silver War Badge, also known as the Wound Badge, for his service, as well as the British War Medal and the Victory Medal.

Maud and Thomas welcomed their first child, Raymond, in 1920, and their second child, John in 1922. The inter-war years seem to be pretty quiet for the family—Maud and Thomas appear on the election registers during these years but as of yet I haven’t found them in other records during this time.[20] In the 1939 Register, Maud and Thomas are working at ’unpaid domestic duties’ and a ’general labourer’ respectively.[21] Thomas is also working full-time as a A. R. P. Warden. A. R. P. Warden’s were at integral part of the Home Front War effort—they patrolled neighbourhoods during the blackout and made sure that everyone was abiding by the rules! This register was conducted less than a month after the United Kingdom declared war on Nazi Germany, and Maud and Thomas were facing the second worldwide military conflict during their lifetimes.

In World War Two, as with World War One, there was a HUGE need for munitions. Royal Ordnance Factory (ROF) Aycliffe was built in Aycliffe, County Durham in 1941. During the war, ROF Aycliffe employed 17,000 people and operated 24 four hours a day.[22] Unlike at Gretna, at Aycliffe cordite wasn’t made, but the workers were filling shells and bullets with powder.[23] This was still very dangerous work—there was accidents and explosions, as Maud would soon find out.

The Women Behind the Women- Munitions work at a Royal Ordnance Factory in the North of England, c 1942 War worker Mrs Wilkinson breaks down fuses at ROF Aycliffe, near Darlington, County Durham. http://media.iwm.org.uk/iwm/mediaLib//21/media-21566/large.jpg

The women workers of Aycliffe were soon known by the moniker ‘Aycliffe Angels’. This was given to them by the infamous Lord Haw-Haw, an English man who worked for the Nazis throughout the war, and regularly broadcast propaganda radio programmes to the UK. Haw-Haw frequently said during his shows ‘the little angels of Aycliffe won’t get away with it.’[24] Not only did this give the workers a sticking nickname, but it also highlighted the importance of their work—it was essential to the war effort.

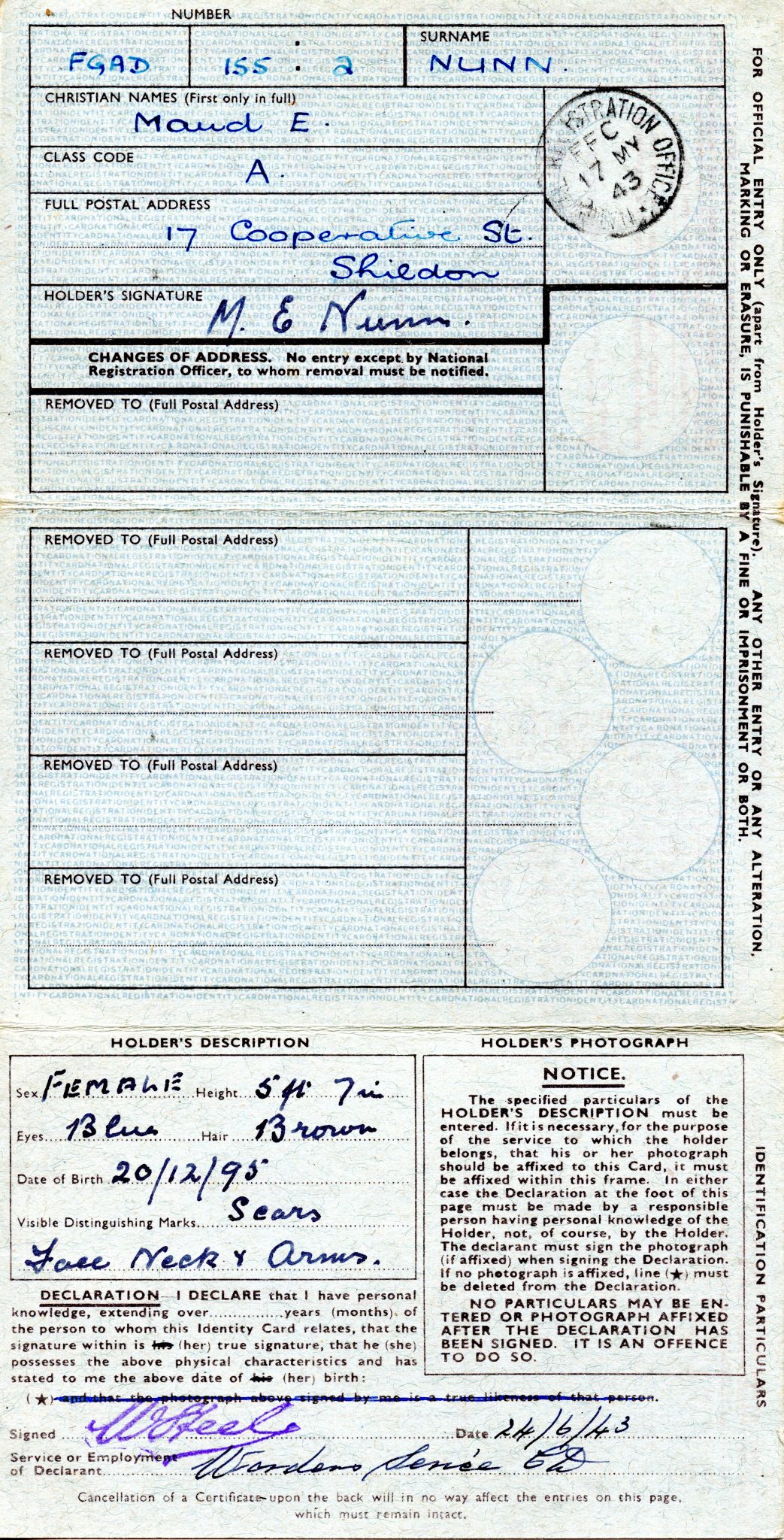

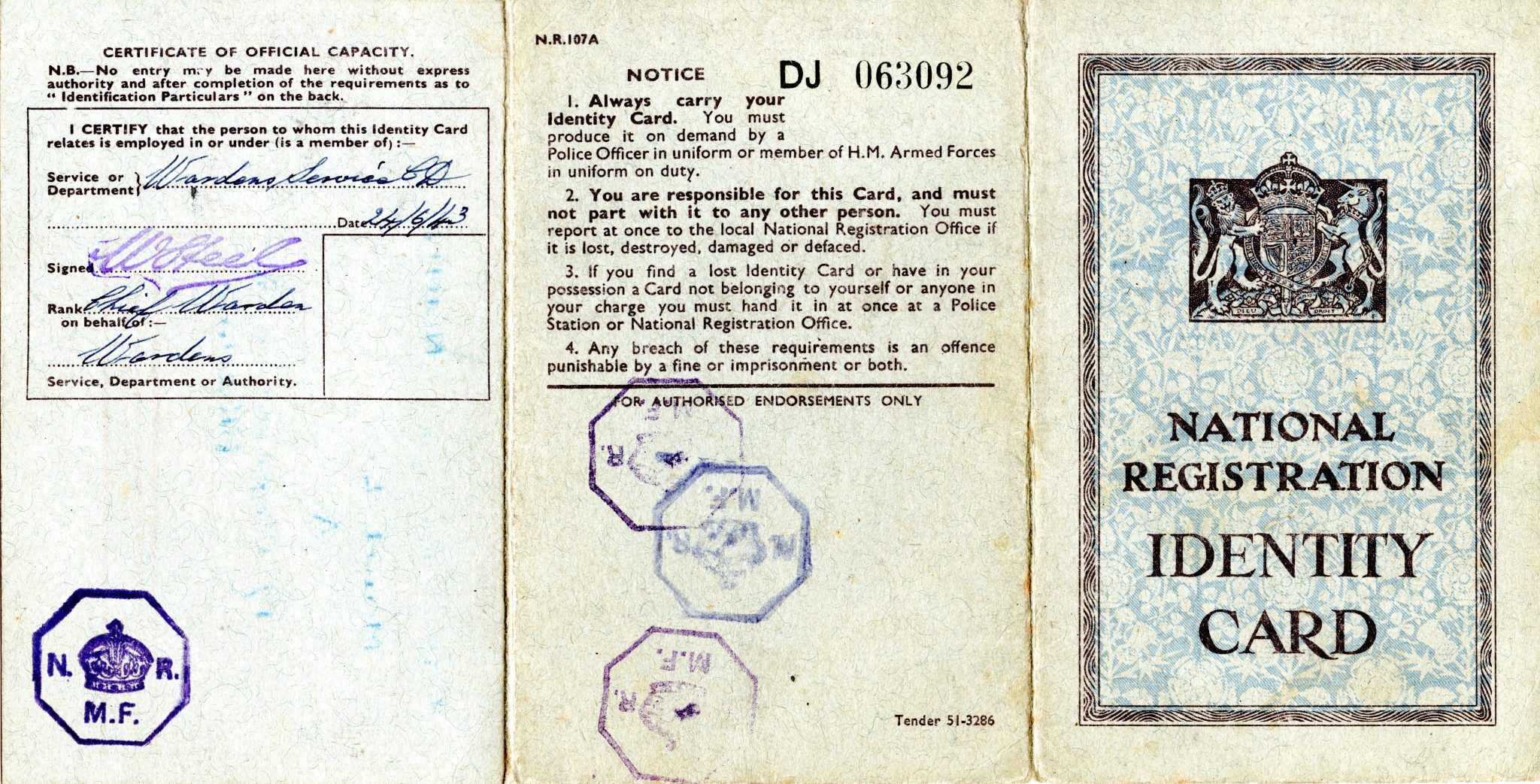

Maud’s identity card, which she would have had to have shown upon entry and exit to the factory.

At Aycliffe, ‘all workers had to wear special shoes and overalls which they put on at the beginning of each shift. They were checked to make sure they didn’t have any flammable items in their possession, like matches and cigarettes, or metal objects like hair grips which might fall into machinery.’[25] This would’ve been very similar procedure to Gretna—I wonder if Maud had a sense of déjà vu when she began working at Aycliffe? Also like at Gretna, the materials they were working with at Aycliffe were dangerous, it ’often causes skin and hair to turn yellow (munitions workers were referred to as ‘canaries’), caused asthma and breathing problems, sometimes made teeth fall out and damaged the lining of the stomach.’[26] The many potential health issues involved in working in munitions would also effect Maud. Later in life, those who knew Maud would note that’ My grandmother…read the newspaper to Mrs Nunn each morning as her eyes had been damaged in the munition factory, so she always wore specifically tinted spectacles.’[27] But the danger didn’t just come from the chemicals–the workers at Aycliffe were also at risk from bombing.[28]

At Aycliffe, ‘all workers had to wear special shoes and overalls which they put on at the beginning of each shift. They were checked to make sure they didn’t have any flammable items in their possession, like matches and cigarettes, or metal objects like hair grips which might fall into machinery.’[25] This would’ve been very similar procedure to Gretna—I wonder if Maud had a sense of déjà vu when she began working at Aycliffe? Also like at Gretna, the materials they were working with at Aycliffe were dangerous, it ’often causes skin and hair to turn yellow (munitions workers were referred to as ‘canaries’), caused asthma and breathing problems, sometimes made teeth fall out and damaged the lining of the stomach.’[26] The many potential health issues involved in working in munitions would also effect Maud. Later in life, those who knew Maud would note that’ My grandmother…read the newspaper to Mrs Nunn each morning as her eyes had been damaged in the munition factory, so she always wore specifically tinted spectacles.’[27] But the danger didn’t just come from the chemicals–the workers at Aycliffe were also at risk from bombing.[28]

In fact, I think Jacky Hyams sums up the work of those at Aycliffe and other munitions factories during World War Two best: ‘To describe their work as hazardous is something of an understatement. The Bomb Girls endured much: exhaustion, fear, sacrifice, separation from loved ones, personal or family tragedy – not to mention the enormous risks to their own lives and physical welfare as they worked. Yet these women, all ages, married or single, from different backgrounds, were a crucial link in the long chain that made up Britain’s wartime endeavour. The men were sent off to fight, fire the bullets, drive the jeeps, fly the planes and drop the bombs. But it was the Bomb Girls who helped make the final victory possible. They too were amongst the country’s true heroes of wartime.’[29]

John D Clare has emerged as the authoritative historian of the Aycliffe factory during World War Two, and has offered valuable critique of the happy and positive image of the Angels that some accounts portray.[30] He argues instead that the reality was far more complex—that ROF factories weren’t great places to work, that the work itself was boring and monotonous, and that they were undervalued and underappreciated—both during the war and for many years afterwards.[31]

Maud (far right) at a reunion of Aycliffe munition workers in the 1980s.

The fight to recognise the work and sacrifice of munitions workers has been long and sadly many Aycliffe workers died before their work was even acknowledged. One of the more recent campaigns has involved the Rotherwas Munitions Group, the National Munitions Association and BBC Hereford & Worcester, who have campaigned for workers to be recognised with a munition workers veterans badge, which you can now apply for if you or a relative worked in munitions in World War Two.[32]

Maud worked at the factory from when it opened in 1941. She later said of her work, ‘I loved the work until the accident. I was in hospital over five months.’[33] The accident Maud spoke of happened in 1943, when ‘some ammunition exploded, and she was very severely burned on her face, arms, hands and chest. She spent six months in Darlington Hospital and then returned to the factory until the end of the war.’[34]

In order to fully recover from this injury, Maud underwent plastic surgery—still a pioneering procedure mostly used on servicemen who suffered awful injuries in the course of their duties. Later in life, she would have a distinctive mark from these injuries; ‘My mam seemed to think that Mrs Nunn had had some plastic surgery on her face – she’d put her hands up to shield her face in the explosion. I think she was one of the first people to have it and her skin was kind of wrinkle free in those areas.’[35]

In addition to her work in munitions, and her recovery from her injury in 1943, it’s important to acknowledge that during the war Maud’s husband was also an ARP warden, and her sons were both away fighting. Raymond served as a lance-corporal [36][37]Later, friends remembered that ’Both of her sons fought in WW2 and were commended for bravery. One of them, I believe, was on the Burma railway.’[38] This must’ve been a stressful and scary period for the whole family—not only was their country at war, but all four of them were intimately involved with that warfare.

World War Two came to an end in 1945, and the factory at Aycliffe closed. I’ve been able to find out a little of Maud’s life after this time. From the copy of her death certificate, it appears that Maud worked as a school dinner lady at some point. In 1954, her husband Thomas, died by suicide at the age of 61.[39] Her oldest son, Raymond, also predeceased Maud, dying in 1984. Even in 2021, over twenty years after her death, Maud is remembered fondly by Shildon locals:

‘Mrs Nunn was as you can see a happy cheerful person, who just lived an ordinary life and got on with looking after a husband and family of boys.’[40]

‘She loved a chat and was always happy to have visitors and this continued when she moved to the nursing home…Overall, I remember her as a kind, strong, practical, determined, smiley old lady.’[41]

But even though Maud had already lived an extraordinary life—bravely taking part in both World Wars alongside raising a family and dealing with both her husband’s and son’s death, she wasn’t done yet. In 1995, Maud turned the big 100! She celebrated with her family and friends at the nursing home in which she lived, and received a letter from the Queen. Her big birthday was reported in the local press and Maud spoke to reporters about her long life. ‘I didn’t want to reach 100, I think it is too long to live, but I am now looking forward to my birthday.’ Maud also recalled the moment she was awarded the OBE, saying: ‘the OBE was the most memorable experience of my life. It was a great honour and I am very proud of the award.’[42] Her son John mentioned in the same article that Maud ’is hard of hearing, but says ’hearing aids are for old people.’’

Maud surrounded by her family at her 100th birthday.

Mrs Maud Nunn (Nee Bruce) OBE passed away on January 8th 1995. Her great-grandson, Andrew, remembers her as ‘a remarkable woman and an inspiration to generations of our family.’ I wholeheartedly agree.

[1] ‘William Bruce’ Census Return for Shop Hill, Coundon, Parliamentary Borough of Bishop Auckland, Public Record Office, folio 140. Retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk

[1] ‘William Bruce’ Census Return for Shop Hill, Coundon, Parliamentary Borough of Bishop Auckland, Public Record Office, folio 140. Retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk

[2] See: The Elementary Education Act 1880 and The Elementary Education (School Attendance) Act 1893. Despite being compulsory by law, the enforcement of such a law was a different matter and many working-class families needed their children to earn a wage as soon as they possibly could.

[3] ‘Maud Bruce’ Census Returns for Tyne Terrace, Coundon, Parliamentary Borough of Bishop Auckland, p. 918. Retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk

[4] ‘Emma Bruce’ Census Returns for Tyne Terrace, Coundon, Parliamentary Borough of Bishop Auckland, p. 922.

[5] Timothy McCracken, Dumfriesshire in the Great War, (Pen and Sword Books, 2015) p. 13.

[6] ‘Brave Gretna Girls: Munition Workers Honoured’ Dumfries and Galloway Standard, 29 August 1917, p. 2.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] ‘Heroism in Factories: Duke of Buccleuch presents medals at Gretna’ Dumfries and Galloway Standard, 19 June 1918, p. 2.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] ‘Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood’ The Edinburgh Gazette, 27 August 1917, issue: 13133, p. 1788.

[13] ‘Brave Gretna Girls: Munition Workers Honoured’ Dumfries and Galloway Standard, 29 August 1917, p. 2.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Heroism in Factories: Duke of Buccleuch presents medals at Gretna’ Dumfries and Galloway Standard, 19 June 1918, p. 2.

[16] England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005, General Register Office, Maud Bruce to Thomas E Nunn, Jan-Feb-Mar 1920, vol no: 10a, p. 483

[17] ‘Thomas Edward Nunn’ Census return for Albert Street, Shilden, Chapel Row, Parliamentary Borough of Bishop Auckland, Public Record Office, folio 44, p. 31. Retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk

[18] Thomas Edward Nunn’ Census return for Albert Street, Shilden, Chapel Row, Parliamentary Borough of Bishop Auckland, Public Record Office, Retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk This probably means he worked as a banksman, a person who dispatched the coals at the pitbank, unloading and loading the cage.

[19] ‘Thomas Edward Nunn’, UK, World War I Pension Ledgers and Index Cards, 1914-1923, service number: 3/8372, reference number: 2/MN/No772, Retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk

[20] England & Wales, Electoral Registers 1920-1932, Durham England

[21] ‘Maud E Nunn’ 1939 England and Wales Register, Borough of Shilden, Public Record Office, Retrieved from http://www.ancestry.co.uk

[22] Royal Ordnance Factory Aycliffe in the Second World War 1939-1945 – The Wartime Memories Project –

[23] Aycliffe Royal Ordnance Factory – Aycliffe Angels (johndclare.net)

[24] | CommuniGate | Why were they called ‘The Aycliffe Angels’? (archive.org)

[25] Colin Philpott, Secret Wartime Britain, Hidden Places that Helped Win the Second World War (Pen and Sword, 2018) p. 4.

[26] Colin Philpott, Secret Wartime Britain, Hidden Places that Helped Win the Second World War (Pen and Sword, 2018) p. 5.

[27] Facebook recollection from a lady who knew Maud as a child.

[28] Colin Philpott, Secret Wartime Britain, Hidden Places that Helped Win the Second World War (Pen and Sword, 2018) p. 5.

[29] Jacky Hyams, Bomb Girls – Britain’s Secret Army: The Munitions Women of World War II (Kings Road Publishing, 2013), p. 14.

[30] RealAycliffeAngelsNN.pdf (johndclare.net)

[31] Ibid. See also: Days before VE Day an explosion tore through the Aycliffe Angels factory – killing eight | The Northern Echo

[32] Apply for a munitions worker’s veterans badge – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[33] ’Munitions Blaze Heroine Maud Reaches Century’, Unknown Newspaper Article, shared by the family of Maud

[34] ’Munition Factory Workers Re-Union a Great Sucess’, Unknown Newspaper article, shared by Maud’s family.

[35] Facebook recollections from a lady who knew Maud as a child.

[37] Supplement to the London Gazette, 13 December 1945, p. 6072.

[38] Facebook recollections from a friend who remembered Maud.

[39] Thomas Nunn’s Death Certificate

[40] Facebook recollections from a person who knew Maud.

[41] Facebook recollections from a person who knew Maud.

[42] Munitions Blaze Heroine Maud Reaches Century’, Unknown Newspaper Article, shared by the family of Maud