The Miracle Workers Research Project began in 2021, with research volunteers striving to find out more about the 30,000 people who worked at HM Factory Gretna in World War One. In the months since, many fascinating and previously unknown histories have been uncovered. Today, volunteer Stuart writes about his research into football at Gretna.

Women’s football is not new and was recorded in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries. One reference, talks of a match between Scottish Border towns of Lennel and Coldstream, on the Ash Wedensday of 1786 (February 21st 1786). A literary magazine The Berwick Museum noted that the female teams did battle with ‘uncommon keenness’. On January 25th 1896 Mrs Graham (Helen Matthew) visited the Warwick Road Rugby Ground in Carlisle with her resident opposition, London & District to slug out an uninspired 0-0 draw. In a later fixture against a Gentlemen’s XI in Penrith, Mrs Graham’s side won 4-3 and it was noted that the ladies played better against the men’s side than they did against fellow women.

Helen Matthew appeared at the Warwick Road Rugby Ground with her side Mrs Graham’s XI in 1896

An increased need for munitions during WW1 saw centres for arms production spring up across the country. A large proportion of the work force employed were women and among the sports they played football was particularly prevalent. By the spring of 1917 few areas in the country did not have a women’s football side. HM Gretna was no different from other centres producing at least three sides. Little, however, is known about these teams with few references of their activities in the press. Sports in general received sparse coverage with hockey limited to one small article; even the Gretna and Dornock men’s leagues only received coverage for one round of fixtures on 23 November 1917. In view of this, women’s football did better than most and from the copy that was produced new details can be revealed.

In a report on the recreation department’s activities, Ernest Taylor noted that ‘one or two’ sides played on pitches supplied by the Recreation Department. He also observed that there was ‘some division of opinion as to the wisdom on encouraging them to pursue this branch of sport’. For members of the Gretna Social and Athletic committee such as Kenneth Wolfe-Barry or Mabel Cotterell, football for women would have been anthemia but it wasn’t quite so out of the ordinary for Ernest Taylor. As a newspaper man in the south east during the 1890s he was familiar with the various sides, including Mrs Graham’s XI. From his time on the committee of the London Football Association he would also have been aware of the motion put forward to the full FA Council in 1902 by Kent FA Chairman, J. Albert, to prohibit league clubs from competing against women’s sides. The Athletic Committee didn’t recognise the women’s sides and they initially weren’t part of formal events. By the same token the sides weren’t prohibited either, the core objective of keeping the workers occupied in the plant and away from outside influences remained paramount.

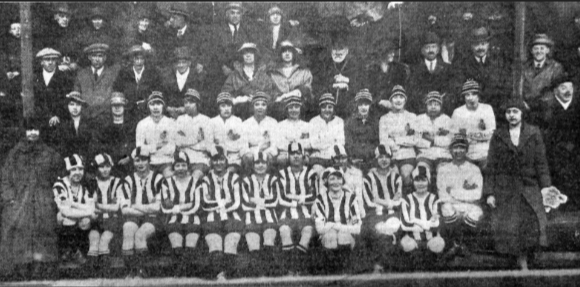

A Gretna side pictured in the winter of 1917 a manager from the Mossband section J.S. Parker can be seen on the far left

The first side from the works appeared during June 1917 for a match against Carlisle Munition Girls at the city’s Brunton Park. The side called the Gretna Girls seem to have been drawn from the ranks of the established hockey teams. One player that has been identified, Jessie Rome Latimer seems to appear in a team picture of the Dornock Hockey side. Born in Annan in 1891 Jessie was active in local music and drama groups taking part in fund rising concerts for war charities. At the Gretna works she performed as part of a variety concert at the Central Hall in Eastriggs on May 17 1917. There are no records of her exploits on the hockey field but there was a substantial write up of the Gretna Girls visit to Carlisle on 9 June 1917.

Possible image of Jessie Latimer from Dornock Hockey side team picture 1917 and a later picture of Jessie taken in the 1920s

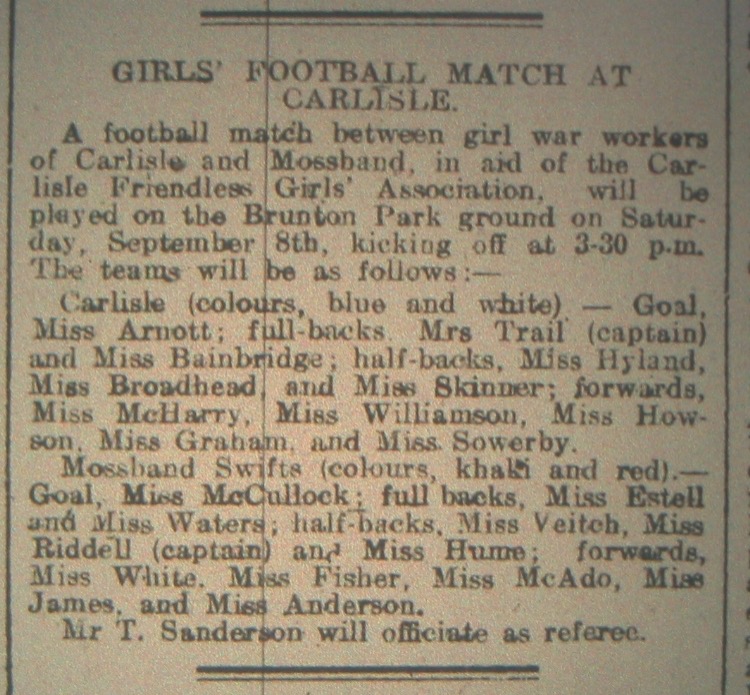

During the summer of 1917 a new side formed at the Mossband section. Called the Mossband Swifts the squad was made up largely from the workers of A Shift. Mossband’s captain was A. Riddell and a possible candidate in the records is Annie Riddell, born in Galashiels in 1899.

Possible image of A. Riddell captain of the Mossband Swifts

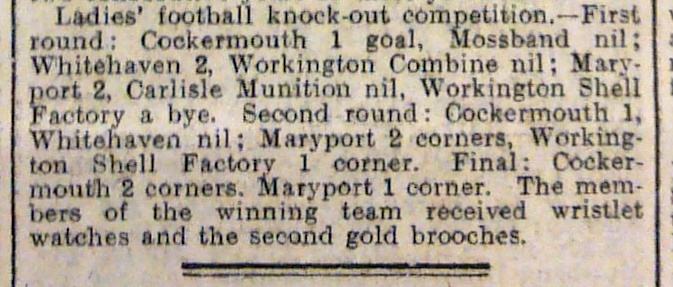

This is yet to be confirmed but another player Mary Annie Anderson has been identified as having played for the side. Born in Scotland at Kirkpatrick Fleming, a village close to Annan, she was 16 when she started playing for the Swifts. An early match for the side was at Maryport where they took part in football competition as part of the Alexander Day Sports Fete. This was one of the early women’s football tournaments the first taking place in Woverhampton in March 1917 these small competitions led to larger events such as the Workington Cup, the Barrow Shield and most famous of all the, Alfred Wood Munition Girls Cup.

Mossband Swifts side August 1917 Mossband section manager Herbert Hawtin can be seen standing second from the right

It wasn’t a good trip to Maryport for the Swifts, however, losing 1-0 in the first round to the eventual tournament winners Cockermouth. On September 15th the Mossband Swifts visited Carlisle where they met workers of the local Cumberland works at Brunton Park home of Carlisle Utd. The Carlisle side went ahead after Miss Graham scored from a first half penalty. In the second period however Mary Anderson took the ball up field and her cross into the area, found M. McAdo to equalise. McAdo scored again but it was ruled offside and another chance just before time was missed, leaving the match tied at 1-1.

Carlisle Journal Aug 1917 Mossband at the Maryport competition

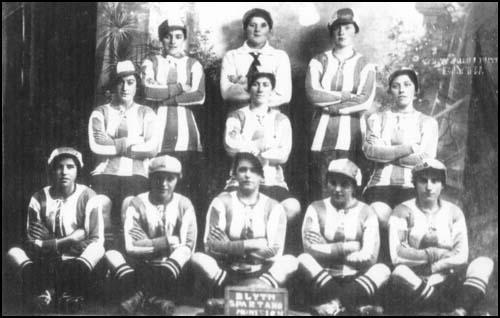

The Swifts made further trips to Carlisle in December 1917 and in January 1918 met a side consisting of wounded soldiers. Mossband players were also part of the Carlisle Munitions Girls side when they took on Blyth Spartans in the spring of 1918. Blyth were well on their way to winning Alfred Wood Munition Girls Cup and the strengthened Carlisle side were no match. Star player Bella Reay bagged a total of five goals as Blyth won handsomely over the two legs.

Carlisle Munition Girls played at Brunton Park from 1917 to 1918

However, attitudes within the Gretna plant towards the women’s teams seemed to change. Matches were included in the programme for fund raising events during May 1918 with new sides forming at Broomhills, an acid section to the far south of Eastriggs, to take part. On 17 August 1918 a women’s football tournament was organised as part of the Munitions workers carnival held at Eastriggs. The tournament included B Shift and C Shift from Broomhills, but again there are few details of the matches or an indication of the eventual winners.

Broomhills Canteen

The report in the Annandale Observer seemed to be more interested in the crowd::

The Ladies Football matches called for a crowd of enthusiastic and amused spectators, who “played the game” in the full sprit of football patronage, cheering and encouraging their favourite team or player as occasion demanded.

This was the last reference to women’s football at Gretna. After the war, Jessie Latimer married a dentist William Armstrong Fyfe in 1920. They lived in Edinburgh and later in Grimsby where William worked at a dental practice on the Grimsby Road until 1929 when William died. Following her husband’s death Jessie moved back to Scotland and lived for many years in Lockerby where she died in April 1958. Mary Annie Anderson settled in Carlisle and in the spring of 1921 married Joseph Irving Lightfoot a former army veteran. By 1939 Mary was working in unpaid domestic work while Joseph was a Railway goods guard. Joseph Lightfoot died in 1964 and Mary Annie Lightfoot in 1976.

Dumfries Ladies and Dick Kerr players at Warwick Road Rugby Ground in 1923

There is no evidence that either player continued with football after leaving Gretna. Many of the old factory sides disbanded after the war but new sides formed and by the 1920s matches were taking place in the district once again. Dumfries Ladies founded in the autumn of 1921 playing against Dick Kerr Ladies at Queen of the South’s ground and in 1923 they met again in Carlisle at the Warwick Road ground. It is often stated that women’s football fizzed out after the FA’s ‘ban’ in 1921 but this is close to being a sporting myth. Although the actions of the football authorities seriously hurt the women’s game, it did continue and matches played during the 1920s and 30s could still attract between ten and fifteen thousand spectators. When a French Select and the successor side to Dick Kerr, Preston Ladies, visited Warwick Road, Carlisle in 1953, they too attracted a large crowd. A former organiser of the Carlisle Munition Girls, Alfred Punnett, was also there and welcomed the sides in his role as Carlisle’s Mayor. There are still local sides competing today, with Annan Athletic Women entering the Scottish League in 2019 and Carlisle United Women winning the Cumberland County Cup in 2015, 2017 and 2018.

By framing footie as a charitable endeavour, women were able to rebut some of the criticism that surrounding their playing of the game.

By framing footie as a charitable endeavour, women were able to rebut some of the criticism that surrounding their playing of the game.

On Boxing Day of the same year, the two teams met again, this time in aid of the Carlisle Nursing Association. This time the Swifts were less fortunate, and they lost 4 -1.

On Boxing Day of the same year, the two teams met again, this time in aid of the Carlisle Nursing Association. This time the Swifts were less fortunate, and they lost 4 -1.