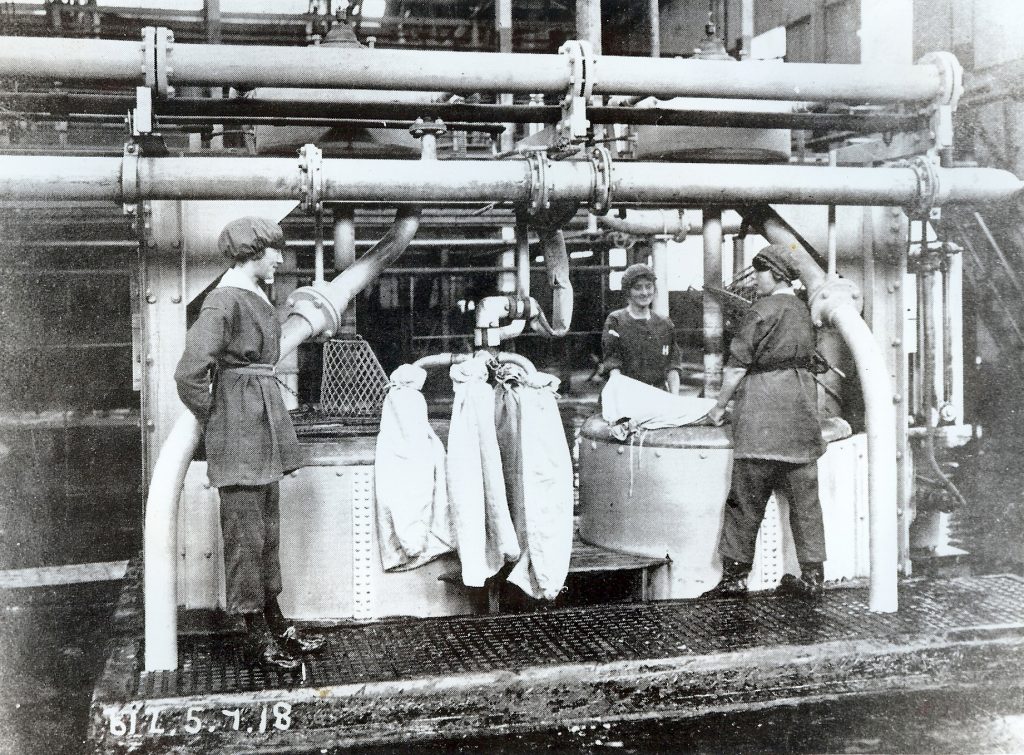

Worker of the Week is a weekly blogpost series which will highlight one of the workers at H.M. Gretna our Research Assistant, Laura Noakes, has come across during her research. Laura is working on a project to create a database of the 30,000 people that worked at Gretna during World War One.

This week’s worker is a little different, because the person I’m highlighting never actually held a job at H. M. Factory Gretna. However, as a journalist and prominent feminist Rebecca West played a critical role in establishing wartime perceptions of munitions workers at Gretna. West visited the factory and wrote an article about the cordite makers in 1916.

Rebecca West was actually born Cicely Fairfield, and was the youngest of three daughters. During her childhood her anti-socialist journalist father abandoned the family. Cecily trained to be an actress at the Academy of Dramatic Art, and it was there where she found the name Rebecca West—a heroine from an Ibsen play. However, after leaving she became a journalist.

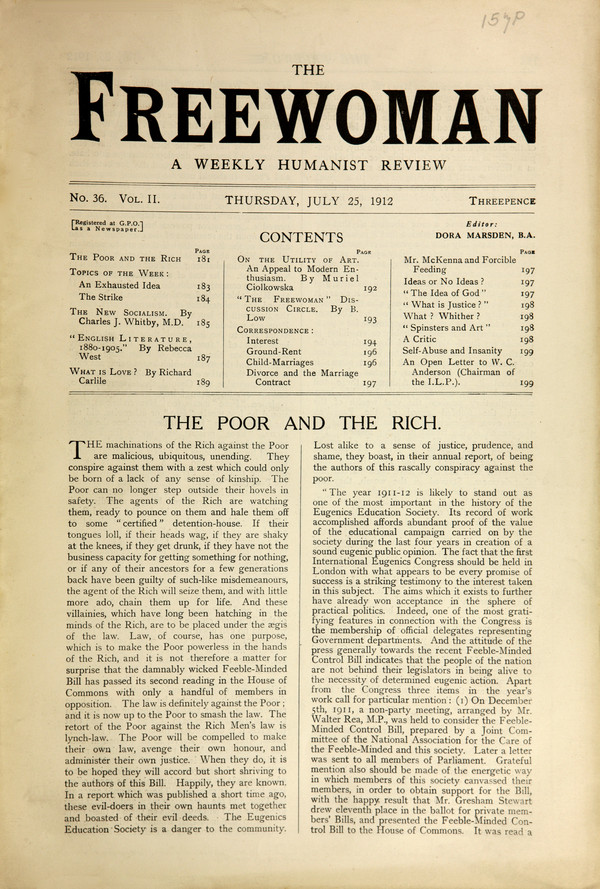

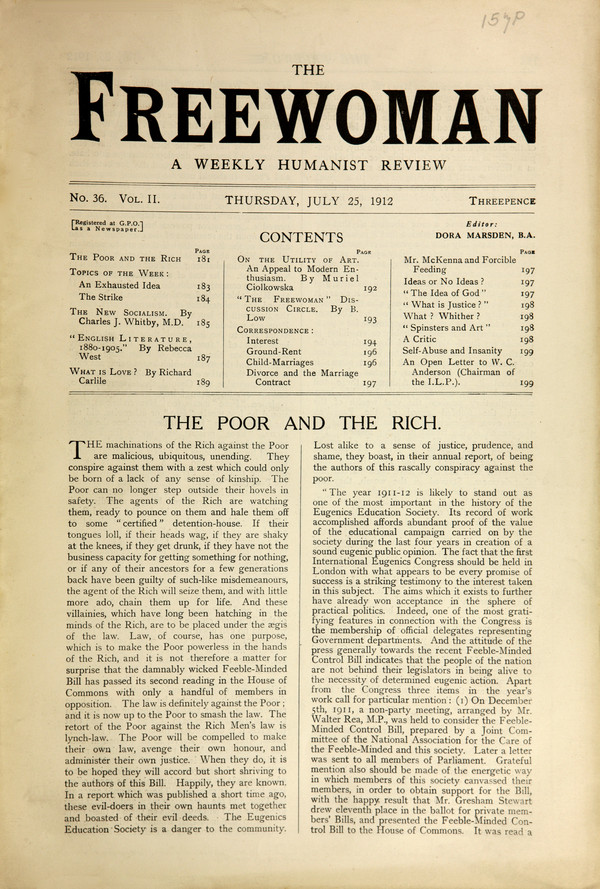

West soon became immersed in the women’s movement. She was involved from the start in The Freewoman, a feminist journal founded by suffragettes Dora Marsden and Mary Gawthorpe. The nineteen-year-old Rebecca wrote prolifically for the publication, on topics as diverse as ‘The Position of Women in Indian Life’,[1] anti-suffrage activist Mrs Humphrey Ward,[2] and book reviews.[3] In doing so, she established a name for herself as a perceptive and cutting writer. The Freewoman, although not particularly successful (it struggled financially and only lasted eleven months), really made its mark by the open discussion of women’s sexuality and free love. Because of this, W. H. Smith refused to stock it, and Mrs Humphrey Ward (one target of Rebecca’s pen!) complained to The Times. Even feminists criticised the journal—Millicent Fawcett tore it up![4] Rebecca’s entry onto the world’s stage was thus tinged with controversy and boundary pushing, both aspects she would encounter throughout her life.

All copies of The Freewoman have been digitized in a brilliant project. See: The Modernist Journals Project (searchable database). Brown and Tulsa Universities, ongoing. www.modjourn.org

After critically reviewing one of his books, Rebecca met and became the lover of the famous novelist H. G. Wells in 1913. Wells, who was married and already notorious for his extra-marital affairs, was twenty-six West’s senior. Rebecca soon became pregnant, and gave birth to her soon Anthony just before the outbreak of war in 1914. So, not only was Rebecca a feminist with socialist leanings, but she was now an unmarried mother who was having an affair with a married man! Scandalous.

During the First World War, like many journalists, Rebecca wrote positive propaganda pieces on the war effort in order to boost morale. One of these was on cordite workers. Published as part of a series called ‘Hands that War’ for The Daily Chronicle, Rebecca detailed the work of the Gretna Girls in her trademark witty prose.[5] She wrote:

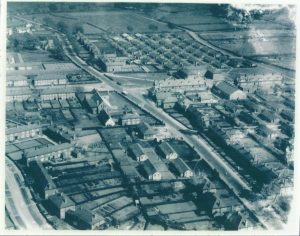

Every morning at six, when the night mist still hangs over the marshes, 250 of these girls are fetched by a light railway from their barracks on a hill two miles away. When I visited the works they had already been at work for nine hours, and would work for three more. This twelve-hour shift is longer than one would wish, but it is not possible to introduce three shifts, since the girls would find an eight-hour day too light and would complain of being debarred from the opportunity of making more money; and it is not so bad as it sounds, for in these airy and isolated huts there is neither the orchestra of rattling machines nor the sense of a confined area crowded with tired people which make the ordinary factory such a fatiguing place. Indeed, these girls, working in teams of six or seven in those clean and tidy rooms, look as if they were practising a neat domestic craft rather than a deadly domestic process.

Rebecca had to wear ‘rubber over shoes’ to enter the factory, because of the danger of explosions. Like Arthur Conan Doyle, who also visited the factory during War, she likened the cordite paste to a food! She said ‘it might turn into very pleasant honey-cakes; an inviting appearance that has brought gastritis to more than one unwise worker.’ This quote made me smile for a number of reasons. Firstly, it implies that some workers actually ate cordite, and were ill because of it. Secondly, The Devil’s Porridge Museum was named after Arthur Conan Doyle’s phrase, could it have easily as been named the Honey-Cake Museum after Rebecca’s?

Above all, Rebecca’s article emphasises the ‘extraordinary’ nature of the work being done and how ‘pretty’ the girls are who are doing it. Rebecca’s emphasis on both the femininity of the workers and their work ethic belies her feminist sympathies—she is refuting the idea that women working strips them of their womanly identities whilst also emphasising their wartime contribution. West also doesn’t shy away from the danger inherent in the work; she describes an accident that happened just days before her visit: ‘Two huts were instantly gutted, and the girls had to walk out through the flame. In spite of the uniform one girl lost a hand.’

The reason why I think Rebecca’s article is so interesting is because it gives us a contemporary glimpse into the lives of munition workers at Gretna, from the mundane (being so tired that they spend the whole day in bed—I can relate) to the extraordinary (‘this cordite factory has been able to increase its output since the beginning of the war by something over 1500%’). The article has Rebecca’s point of view firmly planted on it, but it doesn’t completely depersonalise the Gretna Girls, unlike the many documents and reports written by factory higher ups do. It also shows the inter-connectivity between journalism and wartime propaganda, the importance of munitions production, and the notability of the women who were making munitions. Plus, I still can’t get over Rebecca’s suggestion that some women actually ate cordite!

If you want to learn more about Rebecca’s life, I really recommend the book Rebecca West: The Modern Sibyl by Carl Rollyson.

[1] Marsden, Dora (Ed), The Freewoman, Vol 1, No. 2, 30 November 1911, p. 39. Available: https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:517961/PDF/

[2] Marsden, Dora (Ed), The Freewoman, Vol 1, No. 13, 15 February 1912, p. 249. Available: https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:517961/PDF/

[3] Marsden, Dora (Ed), The Freewoman, Vol 1, No. 17, 14 March 1912, p. 334. Available: https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:518340/PDF/ ;

[4] Lorna Gibb, West’s World: The Extraordinary Life of Dame Rebecca West (Pan Macmillan, 2013); Ray Strachey, Millicent Garrett Fawcett (John Murray, 1931), p. 236.

[5] For more on this series, and the discovery of a brand new article recently found in the archives, see: Kielty, D (2017) “Hands That War: In the Midlands”: Rebecca West’s Rediscovered Article on First World War Munitions Workers. Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, 36 (1). pp. 211-217.