The first Monday in February was designated as #NationalSickieDay when it was discovered that it was the day that the most UK employees take the day off because they’re ill. But pulling a sickie isn’t a new phenomenon. In World War One, thousands of workers moved to the border of England and Scotland to work at H.M. Factory Gretna, making cordite that was essential to the war effort. Many of these workers were young single women, far from home (and parental supervision) for the first time. During the war, the management at Gretna kept a detailed record of absences, and many offenders were taken to a local Munition Tribunal. Dealing with the issue of absenteeism was a BIG problem for management, because maximising production was very important, and absent workers meant that less work was done. Despite this, workers still managed to take an odd sickie here and there. Here are three reasons some munition workers gave for missing work:

-

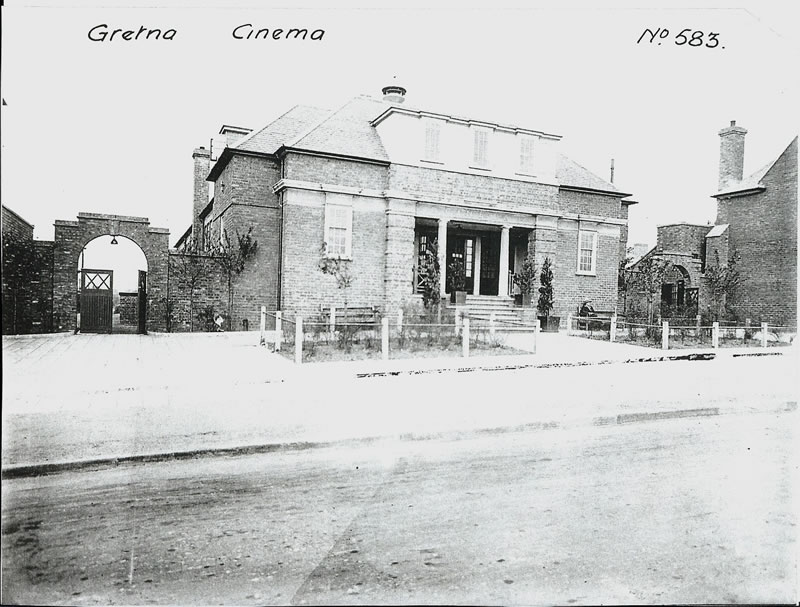

“I wanted to visit the cinema.”

Peggy Leadbetter, Nellie Hoar and E. Atkinson, process workers, and Ann Atkinson, trolley worker, were charged with being absent from work in April 1917. They didn’t seem to take the tribunal process very seriously, the local newspaper recorded that they ‘appeared to treat the matter as a joke, and indulged in frequent sniggers.’ It was also reported that instead of being at work the women were ‘enjoying themselves at dances and pictures in the evening and at the café in the afternoon.’[1]

Peggy Leadbetter, Nellie Hoar and E. Atkinson, process workers, and Ann Atkinson, trolley worker, were charged with being absent from work in April 1917. They didn’t seem to take the tribunal process very seriously, the local newspaper recorded that they ‘appeared to treat the matter as a joke, and indulged in frequent sniggers.’ It was also reported that instead of being at work the women were ‘enjoying themselves at dances and pictures in the evening and at the café in the afternoon.’[1]

The fact that these workers skived off to go to the pictures and dances is not very surprising. The movie business was booming, and there were lots of local picture houses to choose from. Chris Brader states that ‘wherever munitions factories were based, attendances at cinemas rocketed.’[2] Pearl White, the Scarlett Johansson of her day, starred in a number of action films during the War. (A clip from one, The Perils of Pauline, is above!) Perhaps the sniggering girls decided to treat themselves to a movie day rather than a shift at the Factory?

-

“I had to look after my family.”

‘The Sick Child’ by Joseph Clark © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Women were often seen as caregivers.

Another common reason for missing work was family caring responsibilities. During this time, there was a strong cultural expectation that young women look after their family. The shadows of this expectation remain to this day—a recent study found that women’s unpaid care work is a massive reason for gender inequality. This reason for absenteeism was so pervasive at Gretna that it even ended up in the Factory Manual: ‘Many [women] have home calls which cannot be neglected…’[3] Despite this, women who took time because of family issues weren’t always believed.

I know, not believing women?! Who’d’ve thought it?

C. Robertson and Maisie M’Dougall, both process workers at Gretna, were charged with absenting themselves from work in September 1917 without leave or unavoidable causes at a Munitions Tribunal. They pleaded guilty, but argued that they were absent because of family reasons. The Chairman didn’t accept this reasoning, saying ‘There is a great variety of family affairs. You might have a sweetheart. You might have brothers and sisters you want to stay with. You might have someone ill, and so your excuse is rather vague.’[4]

-

“It was raining.”

But it wasn’t just the women workers who took time off. Wet weather was the excuse of George Gilmour, a labourer. It was said at his Munitions Tribunal that he ‘refused to come and wok on nightshift if the work was outside because of his rheumatism, and said that the law forbade his being compelled to work outside in wet weather.’[5] This reasoning wasn’t upheld, and George was fined £3. Although refusing to work in the rain is kind of funny, the fact that George referenced his rheumatism in his reasoning suggests an underlying health condition that maybe wasn’t taken seriously by the Tribunal—a issue still faced by many disabled and chronically ill workers to this day.

So, those are three examples of reasons why workers at H.M. Factory Gretna were absent from their work. As you can see, it’s a lot more complicated than wanting to hole up in bed watching the WW1 equivalent of Netflix—illnesses and absences happened because of a myriad of reasons—and factory management were keen to curtail these absences as much as possible. So on this #NationalSickieDay, why not remember those absentees who have gone before us, and think about changing the narrative.

(P. S. Here are some great wellbeing resources.)

[1] ‘Not a Joke’ Dumfries and Galloway Standard, 18 April 1917, p. 5.

[2] Chris Brader, Timbertown Girls, (Bookcase, 2014), p. 89.

[3] Factory Manual, H.M Factory Gretna archives

[4] ‘Annan Munitions Tribunal, Dumfries and Galloway Standard, 19 September 1917, p. 2.

[5] ‘Munitions Tribunal at Eastriggs’ Dumfries and Galloway Standard, 2 March 1918, p. 4.

If you’d like to know more about HM Factory Gretna, you might be interested in the following items from our online shop: