Worker of the Week is a weekly blogpost series which will highlight one of the workers at H.M. Gretna our volunteers have researched for The Miracle Workers Project. This is an exciting project that aims to centralise all of the 30,000 people who worked at Gretna during World War One. If you want to find out more, or if you’d like to get involved in the project, please email laura@devilsporridge.org.uk. This week, Research Assistant Laura Noakes writes up volunteer Stuart’s research into Mabel Cotterell

Mabel (or Maybel) was born on August 5th 1872 in Walsall, in the midlands. She was the second youngest of a large family of seven children. In the 1881 census the family are living in Somerset. Mabel’s father, George, is working as a solicitor, and the family have a domestic servant named Sarah.

By 1891 Mabel was living with her widowed mother Matilda at Priory Mansions, South Kensington. Her older sister Constance, a literary critic for the Academy magazine, had published her first novel, Strange Gods, in 1889 and was in the process of writing her second, Tempe. Mabel appeared in the 1891 census as a school mistress and boarding with her at Priory Mansions was a Swiss language teacher, Adele Glatz. A 1925 shipping manifest records that Mabel had skills in both German and French, and in the 1911 census she is recorded as living at 106 Beauford Street in Chelsea and teaching at a private school. Constance was also listed as living at this address.

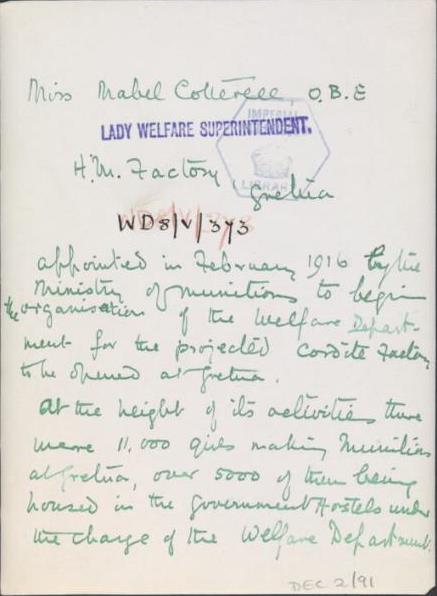

Mabel was appointed by the Ministry of Munitions for the purpose of setting up the Welfare Department at Gretna. She took up her post during February 1916. Besides her regular duties which included administrating and filing records for the female workers she was involved in organising social and sporting events. ‘Miss Cotterell’ appears in many reports of sports events and galas.

© IWM WWC D8-5-373

In the January 5th edition of the British Journal of Nursing, Mabel is highlighted as:

Miss Cotterell has an army of assistants, clerks, matrons and factory supervisors, and as many as 200 new workers arrive in one day. Inevitably the difficulties of administration are not unknown, but, we read, difficulties seem to vanish under Miss Cotterell’s experienced touch.

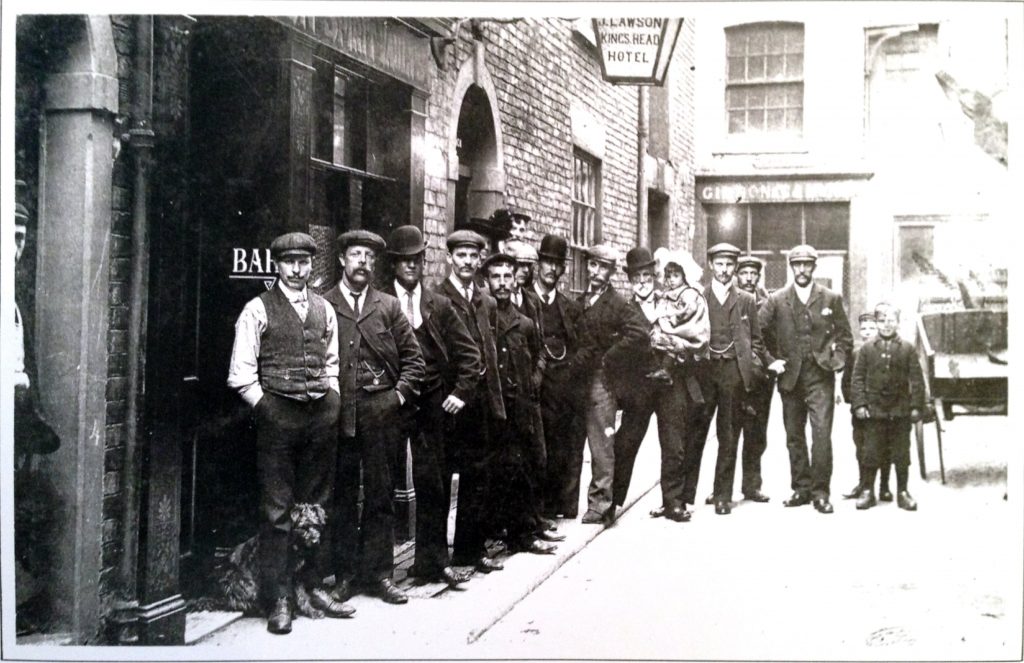

Above photo and this one are from IWM’s First World War Portraits (Women’s War Work) Collection. Catalogue number: WWC D8-5-373

In June 1918, Mabel was awarded an OBE in recognition of her war work.

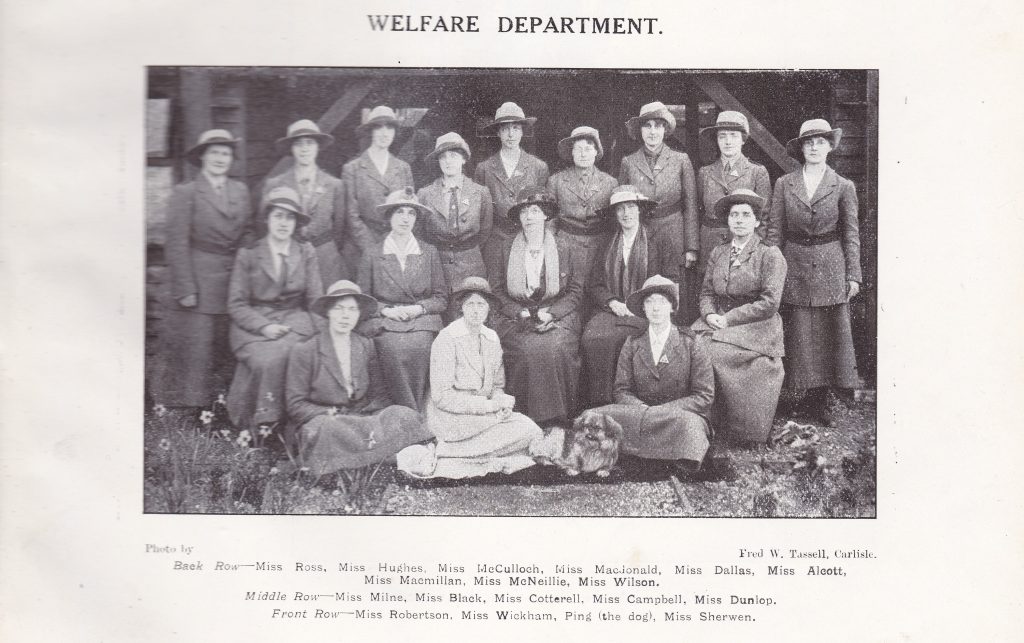

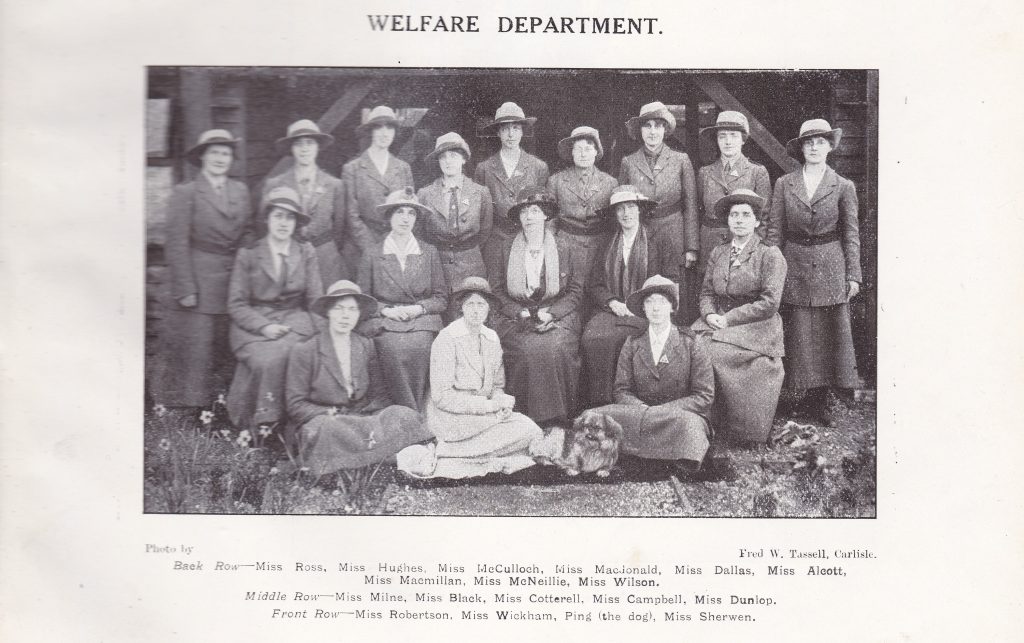

Mabel pictured with her fellow welfare workers in the Mossband Farewell, a magazine put together by HM Factory Gretna workers at the end of the war.

After the war she returned to London living at 20 Downside Crescent N.W.3. It’s likely that Mabel was a supporter of women’s suffrage as she wrote semi-regularly for The Vote, the organ of the Women’s Freedom League, The Common Cause, another suffrage periodical, and The Church League for Women’s Suffrage. Interestingly, the articles Mabel wrote was on a subject related to Gretna–the State Management Scheme. The State Management Scheme began during the war, when the Government took over breweries and pubs in the Gretna and Carlisle area and controlled the sale of alcohol. Mabel was evidently impressed with it, writing “that Carlisle has shown there is a new solution to our problem [of overdrinking].’

In another article, Mabel further expanded on the problems that necessitated the scheme:

In Carlisle, where thousands of navvies had been drafted for the building of townships and factories at Gretna, the regulations and restrictions had quite broken down. Police supervision was utterly inadequate. The crowded public houses, the drunken scenes in the street, the evasion of all control by the publicans eager to reap this golden harvest.

This appears to be the cause to which Mabel dedicated her life to. In several papers she is referred to as the “Secretary to the Women’s National Committee for State Purchase and Control of the Liquor Trade.’

She wrote to local papers on other issues as well. In one letter to the editor of the Westminster Gazette, she criticised experiments on animals, arguing “how can we claim to be gallant defenders of the weak and oppressed so long and we disgrace our humanity with this barbarous practice.” She also acted as the English translator of ‘Hymns to the Night’, a collection of poems written by German poet Novalis,

On January 2nd 1925 she left London aboard the steamer Cardinganshire for Los Angeles arriving on January 25th. Mabel retuned to the US in 1926 visiting New York and in 1939 traveled to the Dutch East Indies. In her later years she lived in Gloucestershire and died on May 20th 1968 at New Nursing Home Cairncross Rad Stroud.