This article was written by Alastair Ritchie, who is one of our young volunteers. He recently completed The Prince’s Trust Award while volunteering in the Museum.

Ammunition Line Display

A while ago the museum was kindly donated 2 rollers and 4 trestles which we believe were used at the Eastriggs or Longtown depot. Since then we have sought to find a place for them, which we have now found (thanks to Neil McGarva for this suggestion). The items have been arranged in a way which will help to demonstrate their use, under the stairs in front of the window so it will be something for people to see when coming in from the car park or walking round the building.

Alastair near the display (which is hard to photograph due to being behind glass). He is holding an ammunition storage box.

Thanks to the efforts of our volunteers Alastair and George along with Digital Marketing Modern Apprentice Morgan, the area has been cleared, cleaned and arranged to ensure it both looks good and gives some insight into how these items might have been used.

If you are interested in some more information on our display then here are a few facts about it…

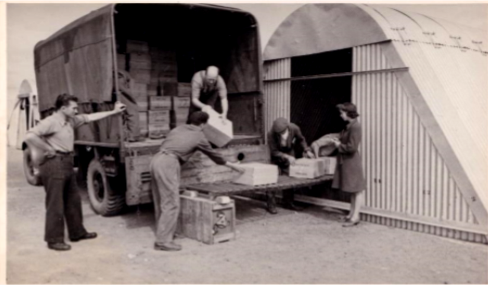

Group of worker using multiple rollers to assist them in moving crates around. This was essentially the rollers job to make moving heavy object safer, easier and most importantly faster.

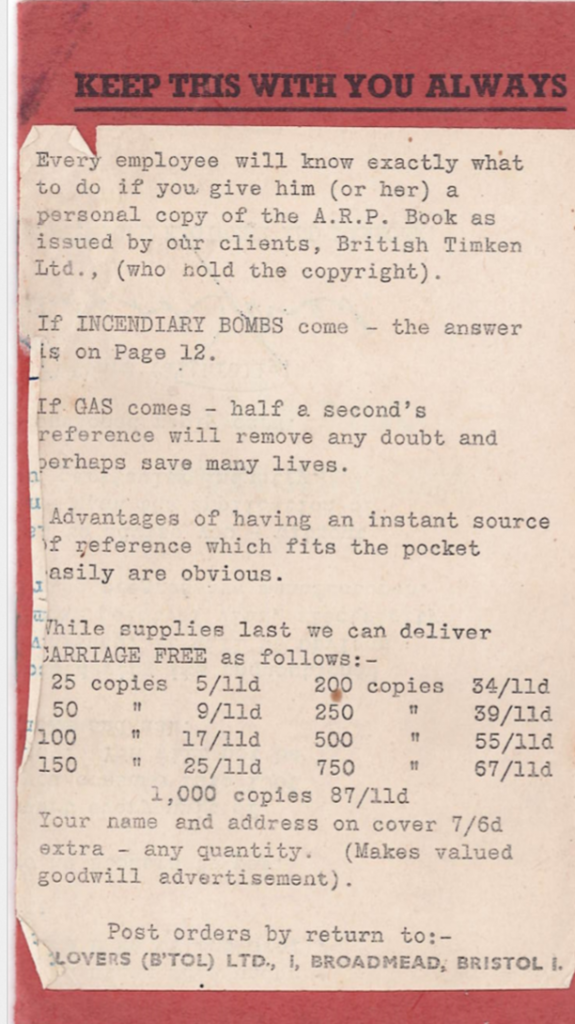

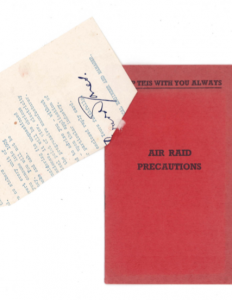

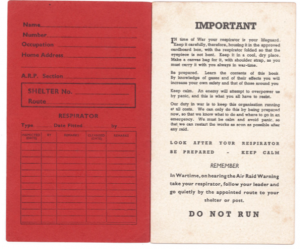

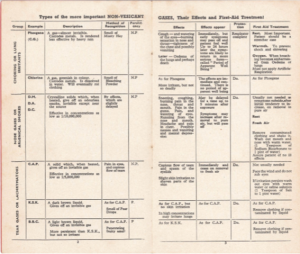

The following book may be of interest if you would like to know more about the depots and the local area in World War Two:

The Solway Military Coast book

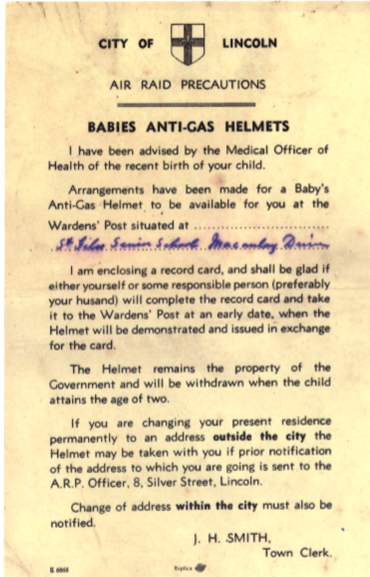

After this article was published, a member of the public came forward with the following information and photographs, we thank him for sharing this with us:

-

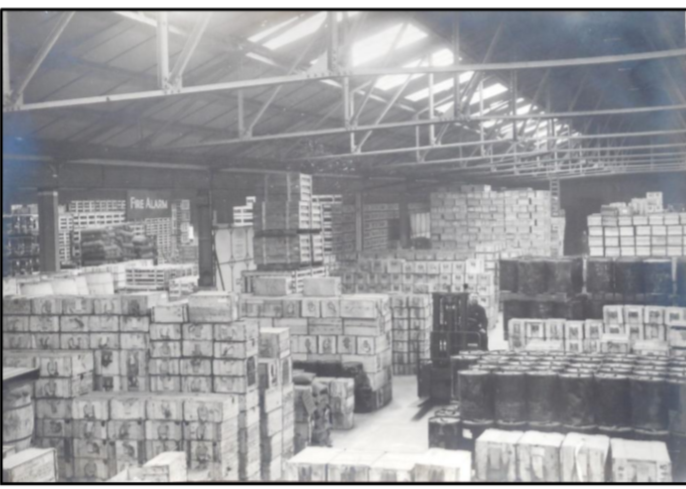

The beginning of the process in what was known as the In-Transit this is where the ammunition/explosives are received into the building

-

Operatives would breakdown the pallets and load the containers/boxes onto the rollers and they would then be pushed through a hatch into the Process area where Ammunition Examiners would carry out various tasks:

-

Safety Inspection

-

Modification

-

Repairs

-

A pedestrian gate in the rollers where examiners could work on both sides of the rollers

-

Once this was done the containers/boxes would be moved along the rollers to the Out-Transit, here operatives would add markings

-

The rollers were used in all types of industry including the ships for deep sea dumping

Just after the war some of the excess ammunition was thrown into the sea

This process was known as Deep Sea Dumping fortunately it is now Banned

Come and visit us when it is safe to do so! Here is a photo of a visitor enjoying a look at our 1940s kitchen.

Come and visit us when it is safe to do so! Here is a photo of a visitor enjoying a look at our 1940s kitchen.