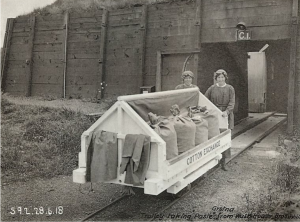

Worker of the Week is a new weekly blogpost series which will highlight one of the workers at H.M. Gretna our Research Assistant, Laura Noakes, has come across during her research. Laura is working on a project to create a database of the 30,000 people that worked at Gretna during World War One.

Hello, and welcome to the very first edition of our new weekly series! This blogpost really demonstrates just how valuable sharing stories with us (and any Museum ) is!. A member of the public recently got in touch with us, enquiring about a lady named Mabel Alice Read.

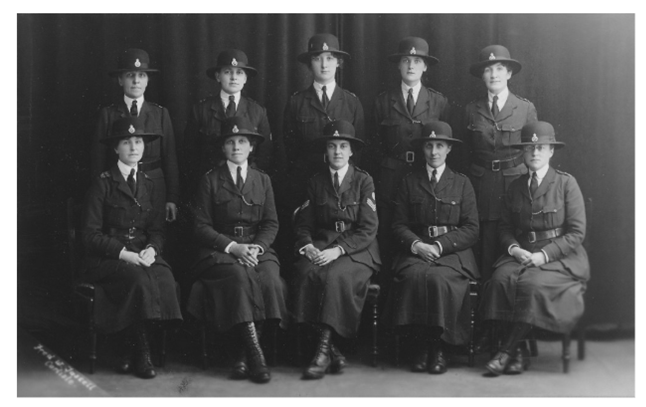

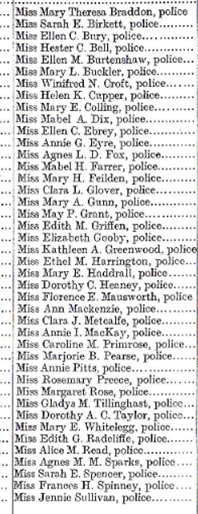

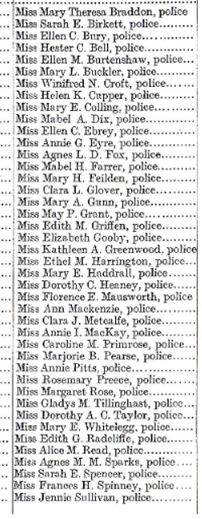

Mabel had been very briefly mentioned in our blog about Women Police Officers at H.M. Factory Gretna. The Women’s Police Service (WPS) was formed in 1915 by Margaret Damer Dawson, and one of its largest wartime units patrolled H.M. Factory Gretna and nearby towns. Over 150 women officers worked at Gretna, and we know very little about most of them.

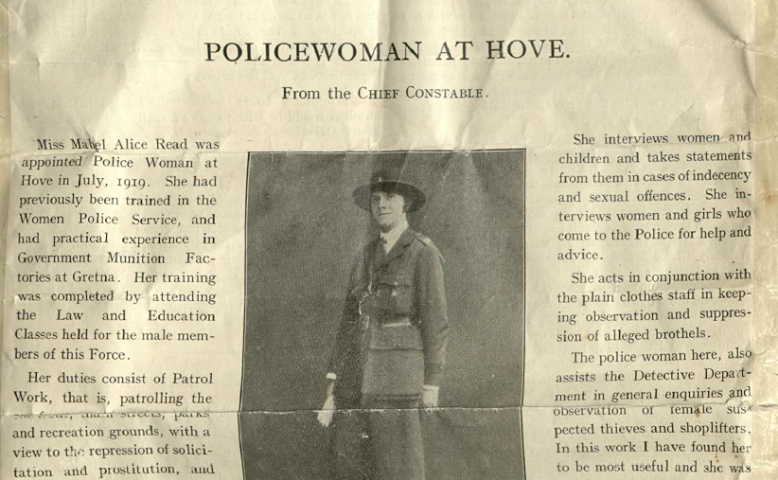

Previously, Mabel’s name appeared on a valuation roll record from Gretna. However, a member of the public reached out to us and shared that Mabel was the focus of an article of the Policewomen’s Review that mentioned, not only her time at Gretna, but also her later work as a policewoman!

Previously, Mabel’s name appeared on a valuation roll record from Gretna. However, a member of the public reached out to us and shared that Mabel was the focus of an article of the Policewomen’s Review that mentioned, not only her time at Gretna, but also her later work as a policewoman!

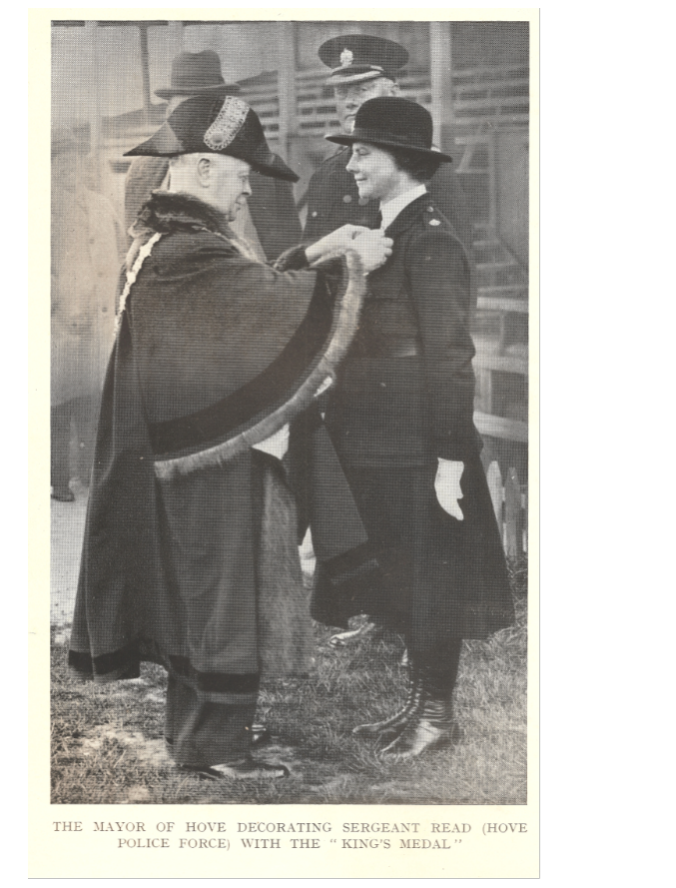

The Policewoman’s Review, Vol III, No, 32., December 1929. Document source: East Sussex Record Office, ESRO ref ACC 6572/3

In this article, it is written:

“Miss Mabel Alice Read was appointed Police Woman at Hove in July, 1919. She had previously been trained in the Women Police Service, and had practical experience in Government Munition Factories at Gretna.”

Although this mention of Gretna is only brief, this article gives us a real insight into Mabel’s professional development as a policewoman. It is clear that after the war, Mabel continued her policework in Hove in earnest. In a report written in October 1921 that summarised her duties, she states that she dealt with: ‘Wayward girls…drunks, women, prostitutes…illegitimate baby cases…lost children’ amongst other duties.[1] This list suggests that Mabel’s policing was very much gendered—she dealt with women and children a lot of the time. This was a crucial aspect of early policing for women, and one of the arguments that proponents of women in policing focused on: that women police officers were better placed to deal with enquiries and issues by women members of the public. Mabel herself asserts this in here report: ‘In cases of attempted indecent assault when I have obtained statements the mother or relative of the child have expressed gratitude at the sordid details being collected by a woman instead of a man.’[2]

Despite this, the Chief Inspector’s praise of the Hove Policewomen was faint. He argued in a letter that ‘a very considerable portion of their time appears to be occupied in typing or other internal administration or filing in the Detective Department’ and stated that he, an assistant inspector, and an inspector agreed that they ‘know of no result effected generally by the women patrol.’[3]

A really interesting case that Mabel was involved in happened in 1928, when she went undercover to ensnare a clairvoyant, Leoni Ward. Mabel visited Ward, who told her ‘that a dark man was in love with her and was about wherever she went, but that he was no good to her. She would marry the dark man and would have two children. The boy would be a great man, the girl a clever musician. Ward also said that Miss Read would travel and see the Sphinx, but must not touch it, as an evil spirit would harm her. She could see Miss Read “standing on a marble slab dressed in white, with pearls and diamonds all down the front.”’[4] At Hove Police Court, Ward ‘was fined £2 for “using palmistry and clairvoyance to deceive.”’ This was against Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act 1834, which prohibited ‘every person pretending or professing to tell fortunes, or using any subtle craft, means, or device, by palmistry or otherwise, to deceive and impose on any of his Majesty’s subjects.’[5]

Palmistry always puts me in mind of Professor Trelawney

It was great to find out more about Mabel’s post-Gretna life and her role as a pioneer policewoman. Thank you so much to the member of the public for bringing Mabel to our attention. I am very excited to go through the records the Devil Porridge Museum has on women police officers when the COVID-19 situation allows. Hopefully, I’ll find out more about Mabel and her fellow officers. If you are doing research on anyone connected to H.M. Factory Gretna, do get in touch on our social media pages or email me at laura@devilsporridge.org.uk. We’d love to hear from you!

[1] Copies of correspondence and reports concerning the work and duties of policewomen in Hove, ESRO Reference: ACC 6572/2, Oct 1921, East Sussex Record Office

[2] Copies of correspondence and reports concerning the work and duties of policewomen in Hove, ESRO Reference: ACC 6572/2, Oct 1921, East Sussex Record Office

[3] Copies of correspondence and reports concerning the work and duties of policewomen in Hove, ESRO Reference: ACC 6572/2, Oct 1921, East Sussex Record Office

[4] ‘”Evil Spirit” Warning”, The Berks and Oxon Advertiser, 27 April 1928, p. 7.

[5] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo4/5/83/section/4