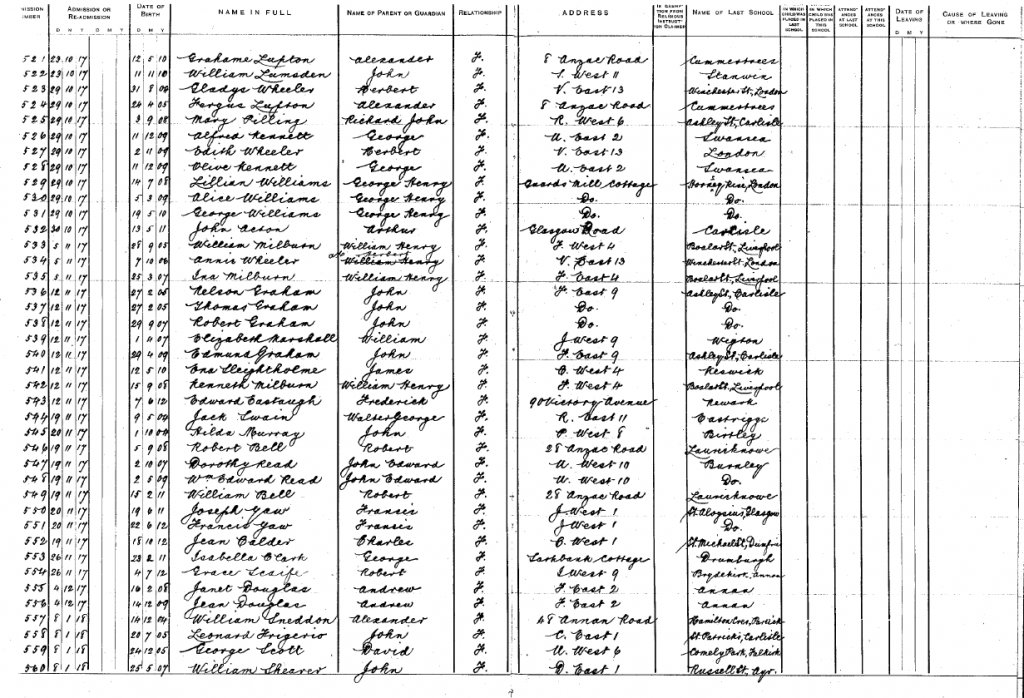

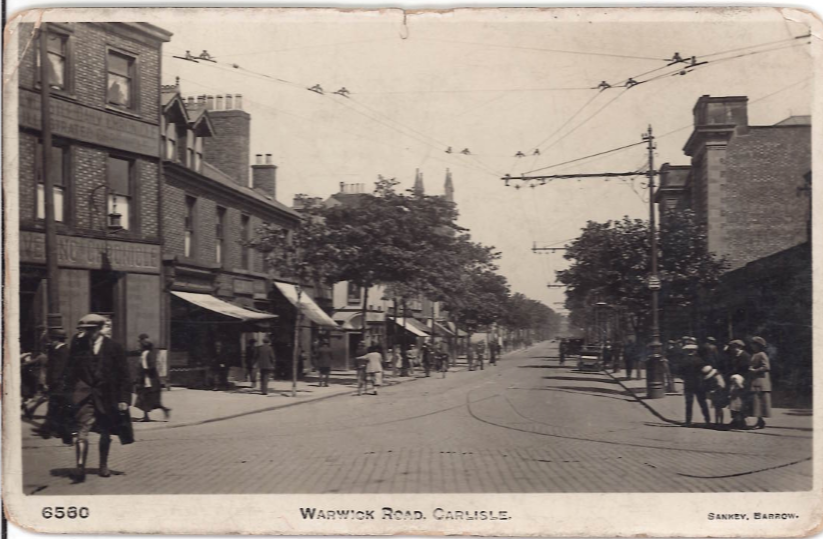

People may think that The Devil’s Porridge Museum is just about Scotland but it isn’t as the women who worked there (and there were 12,000 of them) came from across Britain especially from Northern England including Carlisle and Cumbria.

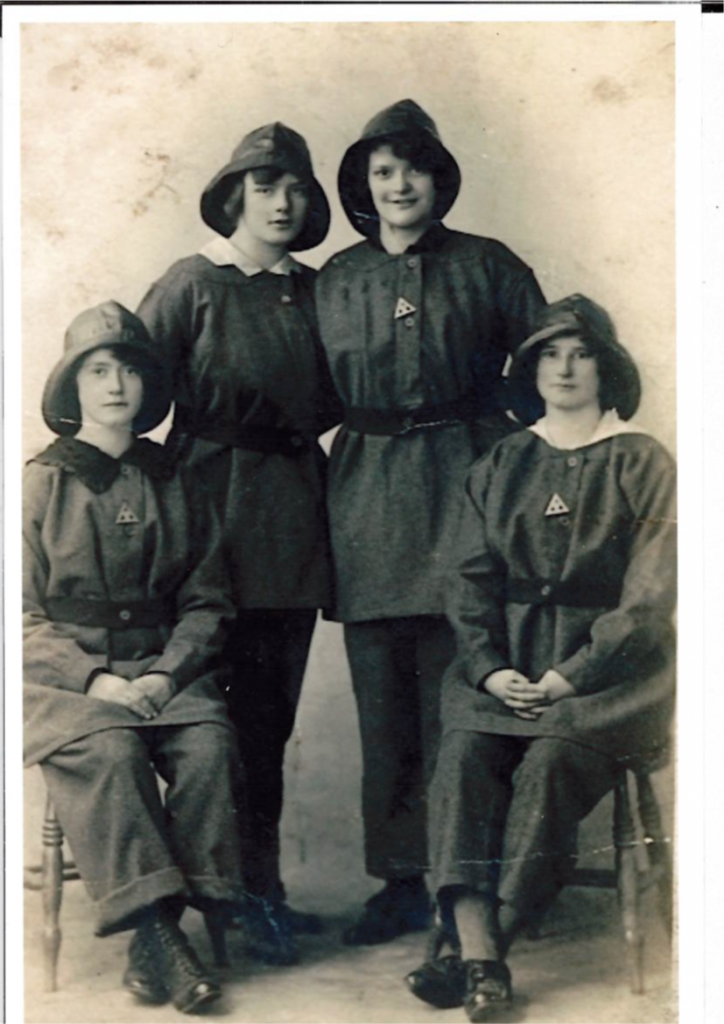

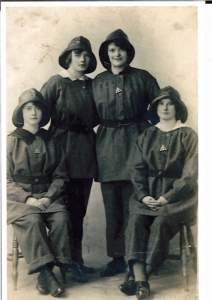

A group of girls in their factory uniforms including Jane Jackson born 1899 from Carlisle

We have dozens of accounts and photos of the so-called ‘Gretna Girls’ mainly provided by family members. Lots of friends and sisters seem to have travelled to HM Factory Gretna to seek work together. Two such sisters were Grace and Margaret Hodgson from Carlisle.

Grace Hodgson aged 21 from Morton Street Carlisle

In 1916, Grace worked in the laundry at HM Factory Gretna. She would have cleaned the uniforms of the girls but also their bedding, towels and other household items. The Factory didn’t just provide work, it also housed many of the girls in purpose built hostels in Eastriggs and Gretna.

Girls working in the laundry at HM Factory Gretna

Grace’s sister, Margaret, aged 19, also obtained a job at the Factory for a number of months. She was employed in the sewing room where she mended the worker’s uniforms. The sewing room also doubled up as a welfare or rest room so Margaret would have seen girls passing out as a result of the toxic fumes they inhaled. One writer described girls rolling around on grass as though drunk because of their exposure to the chemicals needed to produce cordite (also known as the devil’s porridge).

A rest room for the female workers in the factory

In later years, Margaret spoke of seeing girls working at the Factory who had yellow skin, sometimes their skin was a very bright yellow which is why they came to be nicknamed ‘The Canary Girls’.

Group of female factory workers including Ada Annie Thompson from Carlisle

At the start of the War, Margaret had worked at The Atlas Works in Carlisle. She was employed to make shirts for the army. She and fifteen of her friends left after a dispute about pay. They left to work at HM Factory Gretna as it was offering higher wages. The owner of the Atlas works had to increase the wages he was paying because he couldn’t fulfil orders – so many girls were leaving to work at the Factory just a few miles away. This is just one of the fascinating accounts the Museum has.

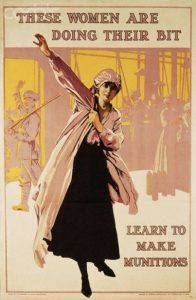

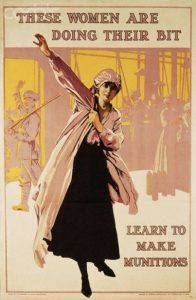

A lot of women were attracted to munitions work for the pay and because they were patriotic

If you would like to find out more about the lives of women working at HM Factory Gretna, this publication is available from our online shop:

Lives of Ten Gretna Girls booklet