Worker of the Week is a weekly blogpost series which will highlight one of the workers at H.M. Gretna our Research Assistant, Laura Noakes, has come across during her research. Laura is working on a project to create a database of the 30,000 people that worked at Gretna during World War One.

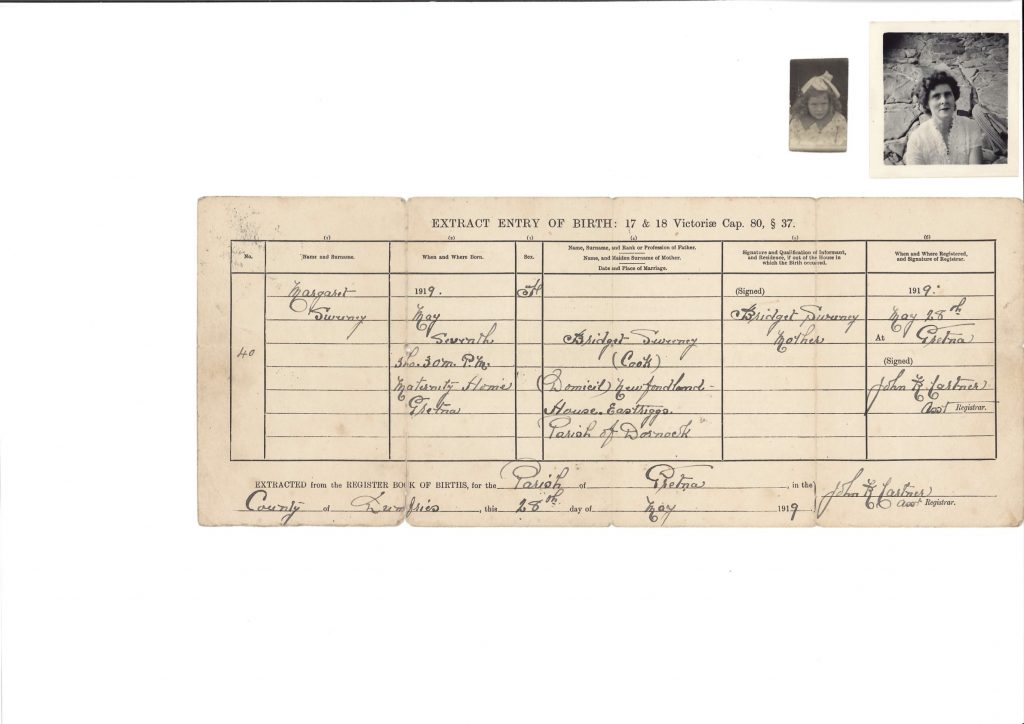

This week’s Worker of the Week is a sad one. I started researching Bridget Sweeney because of a birth certificate:

This is the birth certificate of Margaret, Bridget’s daughter, who was born in 1919. As you can see, Bridget was working as a cook in Newfoundland House, Eastriggs. This was one of the hostels for munitions workers at H. M. Factory Gretna. You can find out more about Bridget and Margaret’s birth here.

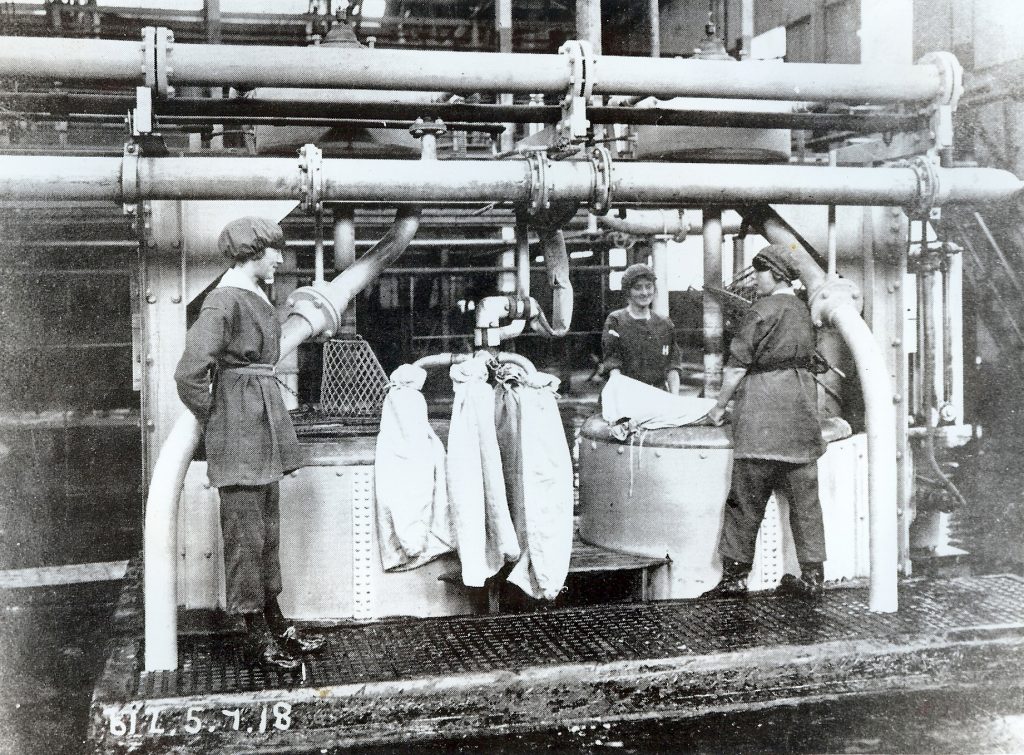

Bridget had been born in Ireland in 1897. She grew up in Donegal and her father worked as a farmer.[1] By 1919, at age 22, Bridget gave birth to daughter Margaret in Gretna. Bridget’s occupation on Margaret’s birth certificate is a cook. This shows the diversity of jobs at H. M. Factory Gretna. Cooks and domestic staff who worked at the hostels where munition workers lived were a crucial part of the factory’s mechanisms. Munition workers worked long hours in the factory, and many relied on the staff of the hostels for those home comforts!

Bridget had been born in Ireland in 1897. She grew up in Donegal and her father worked as a farmer.[1] By 1919, at age 22, Bridget gave birth to daughter Margaret in Gretna. Bridget’s occupation on Margaret’s birth certificate is a cook. This shows the diversity of jobs at H. M. Factory Gretna. Cooks and domestic staff who worked at the hostels where munition workers lived were a crucial part of the factory’s mechanisms. Munition workers worked long hours in the factory, and many relied on the staff of the hostels for those home comforts!

Another interesting thing about Margaret’s birth certificate is that there is no father named, and it appears that Bridget is single. In 1919, single unmarried mothers were frowned upon by society. Bridget subsequently gave birth to three more children: Mary in 1921, Shelia in 1924, and Susan in 1926.[2] On Susan’s register of birth, for the first time a father is noted. This father was Robert Harkness, a farmer, and Bridget’s husband. According to Susan’s register of birth, Bridget and Robert married in September 1925. Shelia’s middle name was also Harkness, which leads me to think that Robert was also Shelia’s father as well. However, I can’t find the register of marriage between Robert and Bridget online, and in Robert’s register of death in 1961, he is recorded as ‘single’ rather than a ‘widower’[3] and in Bridget’s register of death, she is also recorded at single.[4] This makes me think that the two didn’t get married.

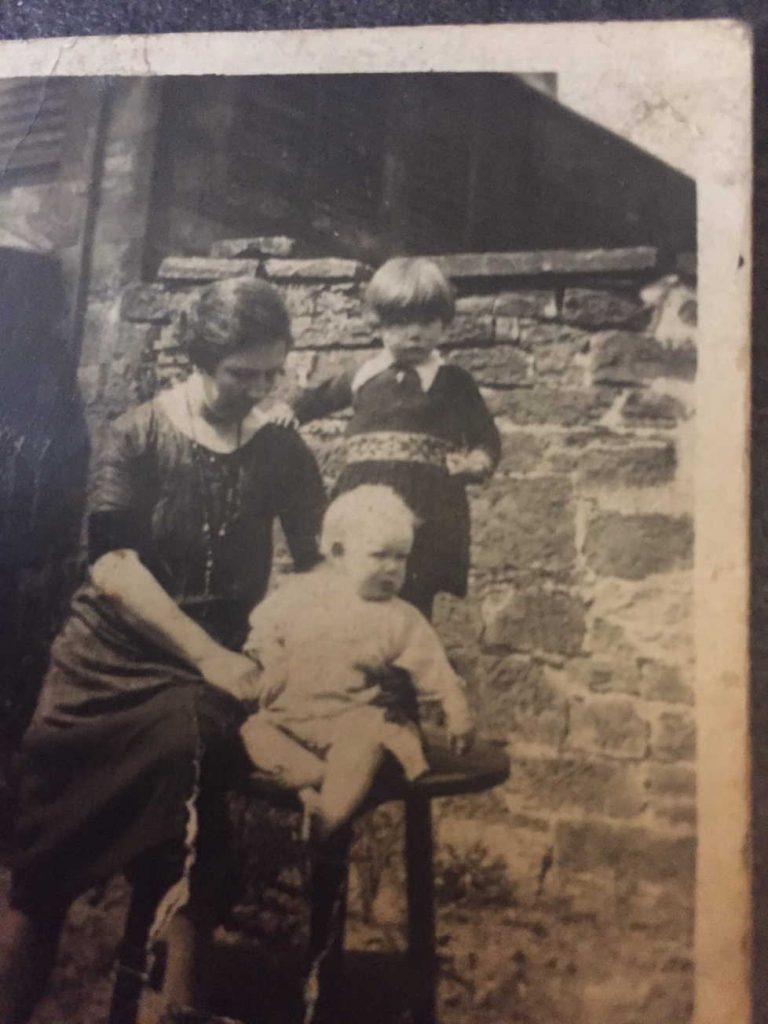

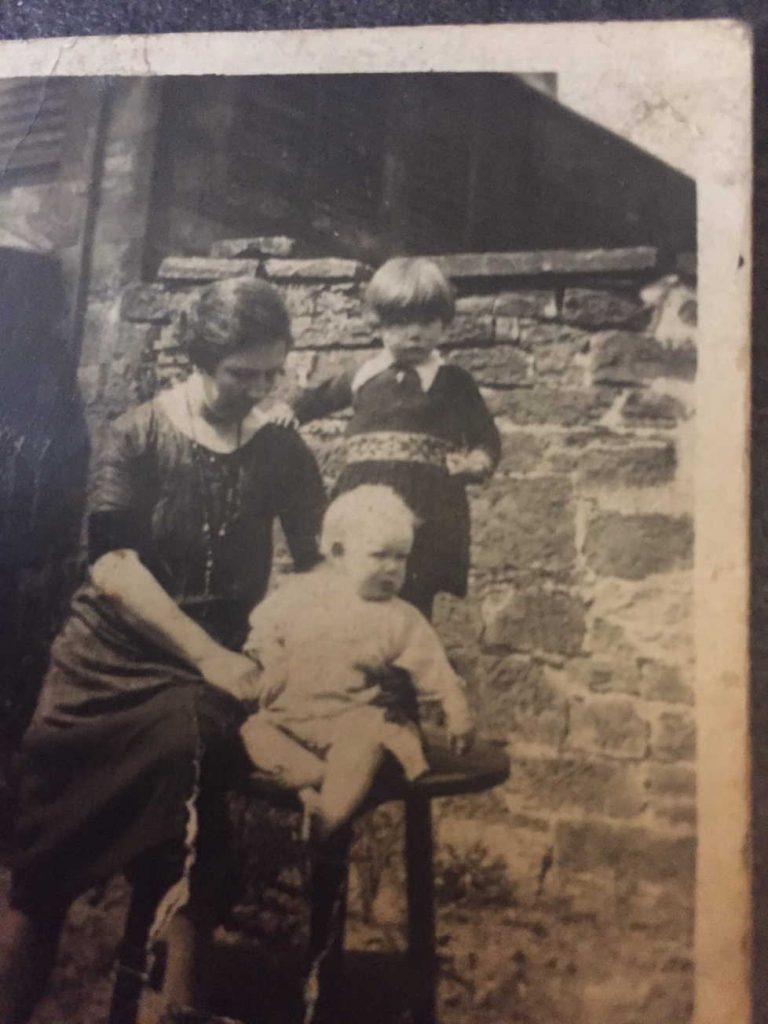

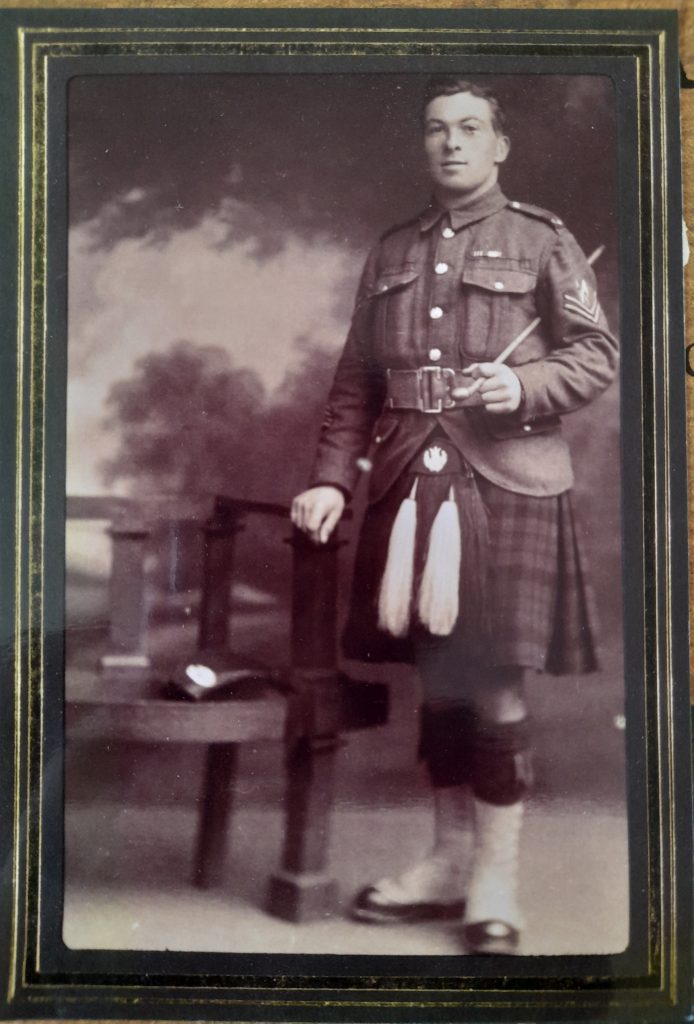

Bridget with two of her children

Bridget’s second oldest daughter Mary sadly died in 1944 aged just 22, in ICI Factory Powfoot, which produced munitions during World War Two. Her cause of death was listed as ‘burning (gunpowder ignition) suddenly.’[5]

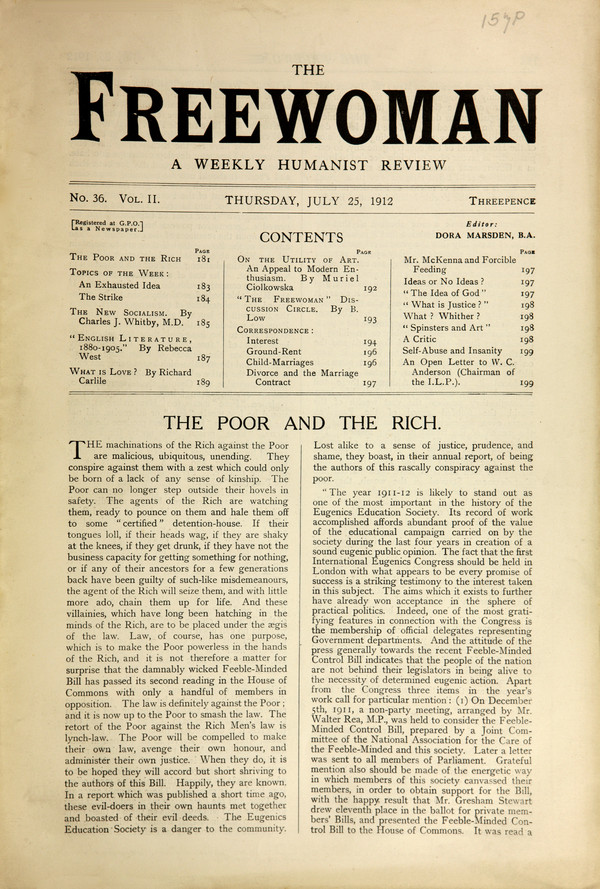

Bridget’s story also has a sad ending. At age 29, after having four children in quick succession, she died in the Crichton Royal Asylum of ‘Exhaustion from Delirious Mania and Broncho-Pneumonia.’[6] The Royal Crichton in Dumfries was founded in 1838 by Elizabeth Crichton and was one of the last and grandest psychiatric hospitals in Scotland. Interestingly, and in another connection with H. M. Factory Gretna, Arthur Conan Doyle’s father Charles was treated there, as was Dora Marsden, feminist and suffragette.[7]

How Bridget ended up in the Crichton is still a historical mystery…

If you enjoyed this blogpost, you might like this booklet (available from the Museum online shop):

[1] ‘Bridget Sweeney’ 1901 Irish Census for Lackenagh, Rutland, Donegal, retrieved from http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1901/Donegal/Rutland/Lackenagh/1179363/

[2] ‘Susan Anderson Harkness’ Birth Register 1926 retrieved from https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/; ‘Shelia Harkness Sweeney’ Birth Register 1924 retrieved from https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/; ‘Mary Clark Sweeney’ 1921 Birth Register retrieved from https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/

[3] ‘Robert Harkness’ 1961 Statutory Register of Death in the County of Dumfries, retrieved from https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/

[4] ‘Bridgit Sweeney’ 1926 Register of Death in the County of Dumfries, retrieved from https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/

[5] ‘Mary Clark Sweeney’ 1944 Statutory Register of Death in the County of Dumfries, retrieved from https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/

[6] ‘Bridgit Sweeney’ 1926 Register of Death in the County of Dumfries, retrieved from https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/

[7] https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/sites/default/files/u_beveridge2.pdf and https://wessyman137.wordpress.com/2016/10/16/dora-marsden-a-remarkable-woman/

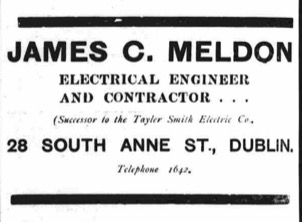

James advertised his business in local papers, and it appears that he was very successful. By 1911, he’d left Dublin to live in Greystones, Wicklow. In 1912, he was involved in the town of Dundalk’s switch to electric lights; his shop there was described as a ‘veritable fairyland of brilliant light.’

James advertised his business in local papers, and it appears that he was very successful. By 1911, he’d left Dublin to live in Greystones, Wicklow. In 1912, he was involved in the town of Dundalk’s switch to electric lights; his shop there was described as a ‘veritable fairyland of brilliant light.’ This is the Meldon family Crest and motto. The motto, pro fide et patria, is Latin for ‘For Faith and Fatherland.’

This is the Meldon family Crest and motto. The motto, pro fide et patria, is Latin for ‘For Faith and Fatherland.’

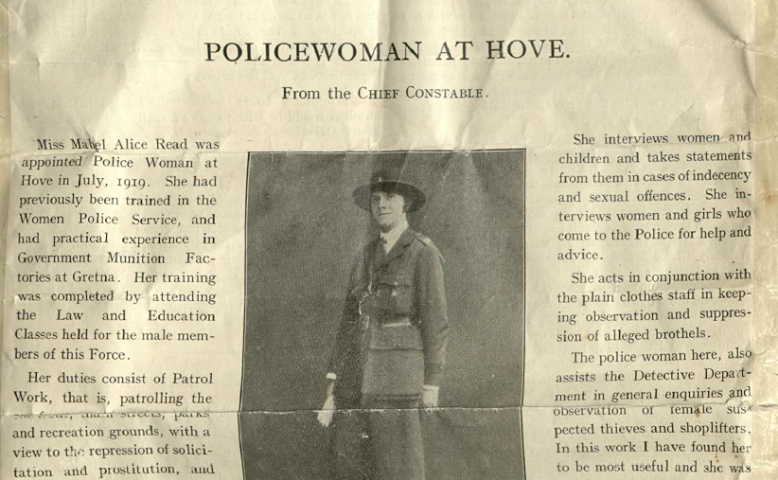

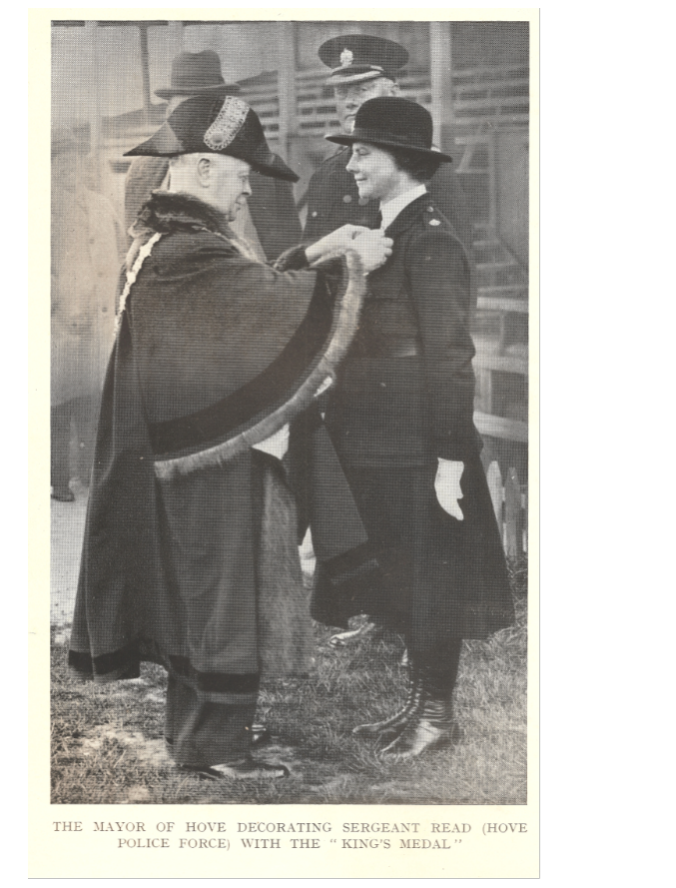

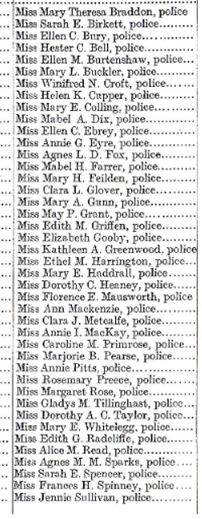

Previously, Mabel’s name appeared on a valuation roll record from Gretna. However, a member of the public reached out to us and shared that Mabel was the focus of an article of the Policewomen’s Review that mentioned, not only her time at Gretna, but also her later work as a policewoman!

Previously, Mabel’s name appeared on a valuation roll record from Gretna. However, a member of the public reached out to us and shared that Mabel was the focus of an article of the Policewomen’s Review that mentioned, not only her time at Gretna, but also her later work as a policewoman!