The 23rd November 2023 marks the 60th anniversary of sci-fi TV show Doctor Who and since our usual Monthly Roundup person is a bit of a fan, she thought it would be fantastic to look at some of the times the show visited the general times or subjects The Devil’s Porridge Museum focuses on. Read on to discover The Devil’s Porridge Museum’s Doctor Who Playlist!

Of course we are NOT saying that these Doctor Who episodes are in any way historically accurate or the views expressed in this program are those of The Devil’s Porridge Museum (Doctor Who is about an alien traveling in time and space in a phone box after all!). This is just for a bit of fun!

SPOILER WARNING! Although, we’ve done our best not to share too many spoilers be aware that some will be included in this blog post and you’ll find more if you choose to follow the links by the clicking on the episode titles.

World War One

The War Games is a last story featuring the 2nd Doctor (Patrick Troughton) and the first few parts are based during World War One. There’s a WW1 ambulance driver and the trenches feature. Of course, it soon turns out that things are not quite how they seem and much more is going on (don’t worry we’re trying not to share too many spoilers here!). This 10 part story and not all the parts are based during World War One, but we still think it deserves a mention.

The Family Blood is the second part of a two part episode (the first part is Human Nature) based prior based prior to World War One. It is only near the end of the this episode were WW1 features. The 10th Doctor (David Tennant) and Martha Jones (Freema Agyeman) also have a beautiful moment of remembrance in this story. Both these things earn it a mention here.

Twice Upon a Time was a Christmas special, which was the 12th Doctor’s (Peter Capaldi’s) last episode. It features a World War One British army captain (played by Mark Gatiss) and also includes a heart-warming scene in relation to this. Well, it is Christmas after all. Football anyone?

World War Two

The Curse of Fendric is a 7th Doctor (Sylvester McCoy) story, which is based during World War Two at a British Naval installation. This is what earns it’s place on this list.

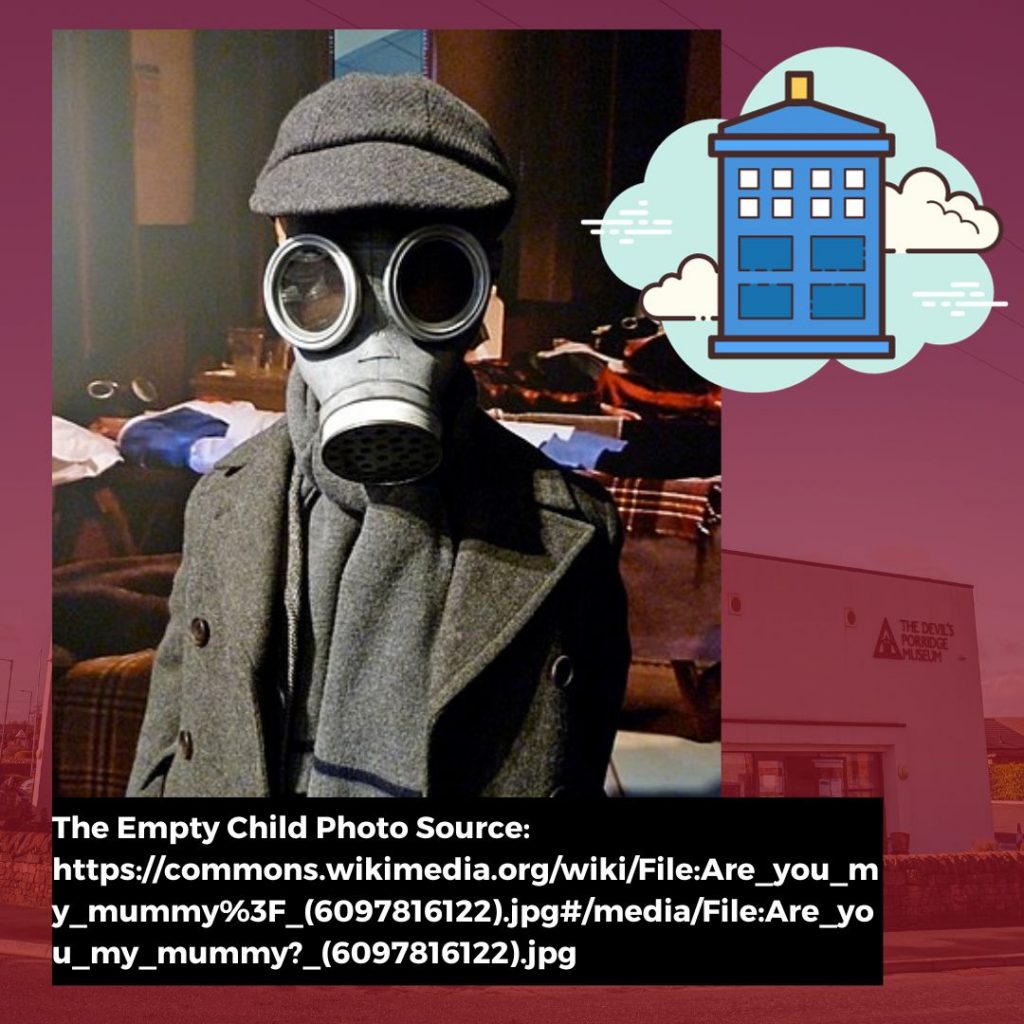

The Empty Child / The Doctor Dances (2005)

The Empty Child and The Doctor Dances are based in London during The Blitz and features The 9th Doctor (Christopher Eccleston). A quick word of warning! This episode has probably one of the most terrifying monsters in Doctor Who and there’s a chilling transformative moment in The Empty Child. (Obviously, this is just the opinion of our Monthly Roundup creator person, but nevertheless you have been warned)!

The Empty Child. Is it just me or does that gas mask seem familiar? Photo source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Are_you_my_mummy%3F_(6097816122).jpg#/media/File:Are_you_my_mummy?_(6097816122).jpg

Victory of the Daleks is based during World War Two, it features Winston Churchill (Ian McNeice) and The 11th Doctor (Matt Smith). As you may have gathered from the title it does feature some of The Doctor’s best known foes, or the daleks (we did say these episodes might NOT be historically accurate didn’t we?). Look out for the jammy dodger.

The Window, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2011)

This is another Christmas special, this time featuring The 11th Doctor (Matt Smith). The episode is based in 1941 and there’s a few moments inside a Lancaster Bomber, which is why we’ve included it here. We do have to say that it may feature a Christmas Eve excursion to another planet and some rather wooden people though!

Part 2 of Spyfall features the 13th Doctor (Jodie Whittaker) and spends some time in Paris during World War Two. The episode also features WW2 British Resistance agent Nora Inayat Khan (Aurora Marion). This is what earns it’s place as the most recent episode on the list. However it’s important to note that not all this episode is based during World War Two.

Chapelcross Nuclear Power Station

Ok, obviously there’s no Doctor Who episodes based explicitly around Chapelcross Nuclear Power station, but what about one which was filmed at a nuclear power station? Yes the connection may be a wee bit thin, but this is just for a bit of fun so bear with us!

“Eldrad must live.”(Can you talk about The Hand of Fear without saying that?) The Hand of Fear features The 4th Doctor (Tom Baker) and Sarah Jane Smith (Elizabeth Sladen). Some of this story was filmed at Oldbury Nuclear Power Station in Gloucestershire (we’re pretty sure that this probably wasn’t the bits on the alien planet though), which is why we’ve included it here.

So there you are! That’s the end of The Devil’s Porridge Museum’s Doctor Who Playlist. Now if your ever wondering what Doctor Who episodes to watch before or after visiting The Devil’s Porridge Museum you’ll know just which ones! Are there any you think we missed? Or is there is any more Doctor Who episodes you think deserve a mention? Why not let us know on our Facebook or Twitter pages?