LGBTQ+ History Month is celebrate every year in February, and aims to bring awareness to often neglected areas of history through increasing the visibility of queer folk throughout history. 2021’s theme is “Body, Mind, Spirit”, so it’s only right that The Devil’s Porridge Museum that the Devil’s Porridge Museum celebrates a woman local to Gretna.

Flora Murray was born in 1869 and grew up in Dumfriesshire. She the daughter of a retired naval commander, the fourth of six children, and part of a prominent local family. Flora’s middle-class upbringing allowed her to take advantages of the improvements in girls’ education: she attended schools in both London and Germany.

Flora’s love of learning didn’t end there. In 1890, at the age of 21, she undertook six months training as a nurse probationer at the London Hospital. Deciding on a career in medicine, she then enrolled at the London School of Medicine for Women—the first medical school in Britain to train women doctors. Like many women doctors, Flora then worked in a low-paid and low-status job as a medical assistant in an asylum in Dumfriesshire. Women medical professionals were often never even considered for roles in mainstream hospitals because of the male dominated appointment boards.[1] Flora then completed her education at Durham University, getting her Bachelor of Medicine in 1903 and her Doctor of Medicine in 1905.

Doctor and Suffragette

After graduating Flora worked as a medical officer at the Belgrave Hospital for Children before getting a job as an anaesthetist at the Chelsea Hospital for Women. In 1912, she co-founded, with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the Women’s Hospital for Children. The hospital’s purpose was to care for the working-class children of the local community, and its motto was “deeds, not words.”—which might give you a slight clue to the two co-founders’ women’s suffrage leanings.

After graduating Flora worked as a medical officer at the Belgrave Hospital for Children before getting a job as an anaesthetist at the Chelsea Hospital for Women. In 1912, she co-founded, with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the Women’s Hospital for Children. The hospital’s purpose was to care for the working-class children of the local community, and its motto was “deeds, not words.”—which might give you a slight clue to the two co-founders’ women’s suffrage leanings.

Flora was a committed suffragette. Although she was never arrested or force-fed in prison like many of her suffragette sisters-in-arms, she played a critical role in the militancy of the Women’s Social and Political Union. She treated suffragettes who were force-fed in prison, caring for them until they had recovered. After the Cat-and-Mouse-Act came into force, she was even put under surveillance by Scotland Yard because officers suspected she was helping suffragettes evade recapture.[2] She was also a vocal opponent of force-feeding, arguing that it irretrievably harmed some women’s health.[3]

World War One

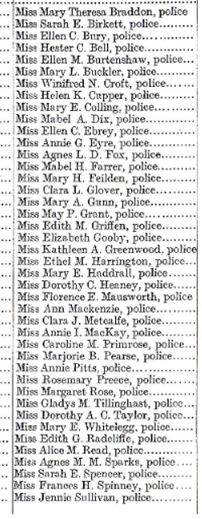

The Staff of Flora and Louisa’s WW1 hospital in Paris.

By the outbreak of war in August 1914, Flora was an experienced doctor. But WW1 changed everything. Teaming up with Louisa Garrett Anderson (more on her later!) again, they formed the Women’s Hospital Corps. Knowing that the British Government were not particularly fond of women doctor’s (they’d already told fellow medical woman Elsie Inglis to “go home and sit still” when she approached them about opening a hospital unit), Flora and Louisa instead went to France.[4] There they opened up a hospital in a hotel in Paris. The injuries and illnesses treated during war were world’s away from their pre-1914 work. Flora’s practice went from being mainly focused on women and children to working on men with horrific wounds. Medicine had to adapt and develop quickly. Despite these obstacles, Flora and Louisa’s hospital was such a success with patients that by 1915 they were invited by the British Government to run a large hospital in London. During the war, the Endell Street Military Hospital, which was often referred to as the ‘Suffragette Hospital’, treated almost 50,000 soldiers.[5]

Flora working at Endell Street Military Hospital

Gay Icons: Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson

Louisa has been mentioned frequently in this blog so far, because she worked closely with Flora over many years. Louisa was also a doctor, and came from a VERY prominent family. Her mother was Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman to qualify as a physician in Britain, and her aunt was Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the constitutional suffragists. The two women shared many interests—feminism, medicine and a commitment to the suffragettes—Louisa had even spent time in prison for the cause!

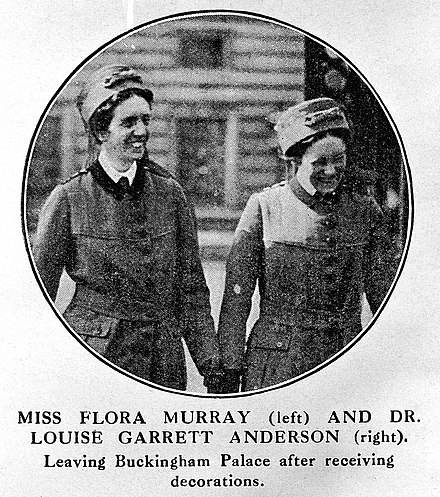

Flora and Louisa after receiving CBEs in 1917.

But not only were the two partners-in-work, they were also partners-in-love. Much has been written about the invisibility of lesbians in history, and many historians have commented on the blurred lines between close friendship and women who love women.[6] However, in the case of Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson, I believe they were clearly romantic partners. Here’s my evidence:

-

Flora had past relationships with women. She’d lived with Dr Elsie Inglis in Scotland for many years and Rebecca Jennings posits that they were in a relationship.[7]

-

Flora dedicated her book, Women as Army Surgeons, to Louisa. It read: ‘To Louisa Garrett Anderson | Bold, Cautious, True and my Loving Companion.’ If that isn’t a declaration of love, I don’t know what is.

-

Flora referred to Louisa as “my loving comrade” and Louisa told her sister-in-law that the women hated being apart.[8]

-

They also wore matching diamond rings![9]

-

Finally, the two women even share a grave with the words “we have been gloriously happy” written upon it.

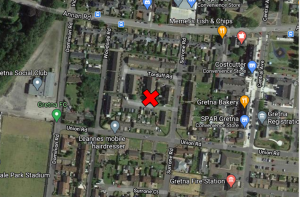

Flora’s Gretna Connection

So now we’ve learnt all about Flora’s incredible war-work and her loving relationship with Louisa, how was she connected to H.M. Factory Gretna? Well, apart from being a local girl, Flora also paid a visit to the Factory in 1918. Her brother, Major Murray, was standing as a parliamentary candidate for Dumfriesshire, and Flora addressed meetings of women electors to express her sister-ly support.

We’re very proud of Flora’s connection to H.M Factory Gretna and we’re also proud to celebrate her the LGBTQ+ History Month!

For more information on Flora and her WW1 work, I really recommend Wendy Moore’s book Endell Street: The Women Who Ran Britain’s Trailblazing Military Hospital.

[1] Wendy Moore, Endell Street: The Women Who Ran Britain’s Trailblazing Military Hospital (Atlantic Books, 2020) p. 13.

[2] The 1913 Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, more commonly known as the Cat and Mouse Act, was a piece of legislation that allowed for the early release of hunger striking prisoners who were ill, and also allowed for their recall to prison once they’d recovered. Wendy Moore, Endell Street: The Women Who Ran Britain’s Trailblazing Military Hospital (Atlantic Books, 2020) p. 24.

[3] Cowman, Krista, Women of the Right Spirit: Paid Organisers of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) 1904-18 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), p. 178.

[4] Read more about Elsie Inglis’ wartime experiences in Eileen Crofton’s The Women of Royaumont A Scottish Women’s Hospital on the Western Front, (Birlinn, 1999)

[5] Geddes, Jennian F. “Deeds and words in the suffrage military hospital in Endell Street.” Medical history vol. 51,1 (2007): 79-98.

[6] See Sharon Marcus, Between Women Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England, (Princeton University Press, 2009) and Martha Vicinus, Intimate Friends Women Who Loved Women, 1778-1928, (Chicago University Press, 2004).

[7] See Rebecca Jennings, A Lesbian History of Britain: Love and Sex Between Women Since 1500, (Greenwood World Publishing, 2007)

[8] Wendy Moore, Endell Street: The Women Who Ran Britain’s Trailblazing Military Hospital (Atlantic Books, 2020) p. 27.

[9] Wendy Moore, Endell Street: The Women Who Ran Britain’s Trailblazing Military Hospital (Atlantic Books, 2020) p. 27.

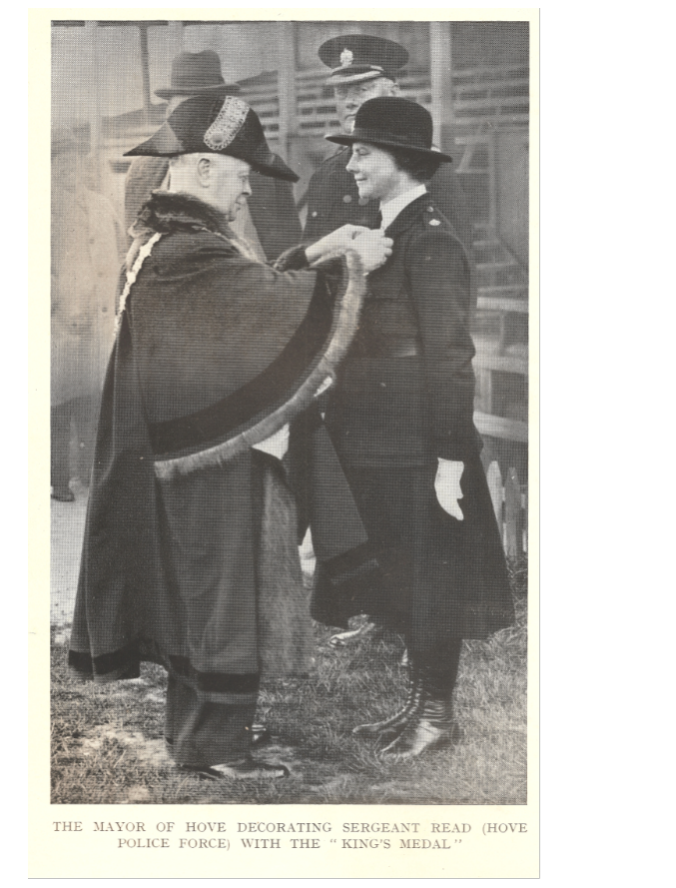

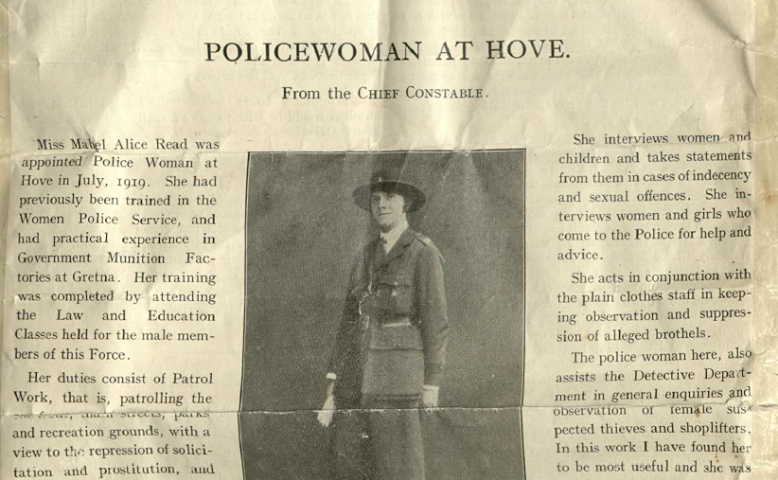

Previously, Mabel’s name appeared on a valuation roll record from Gretna. However, a member of the public reached out to us and shared that Mabel was the focus of an article of the Policewomen’s Review that mentioned, not only her time at Gretna, but also her later work as a policewoman!

Previously, Mabel’s name appeared on a valuation roll record from Gretna. However, a member of the public reached out to us and shared that Mabel was the focus of an article of the Policewomen’s Review that mentioned, not only her time at Gretna, but also her later work as a policewoman!

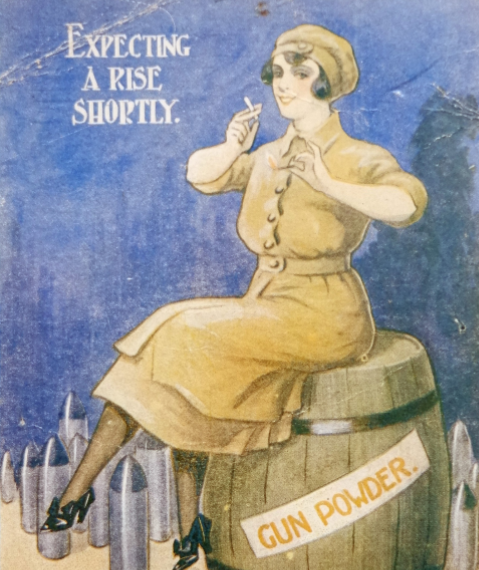

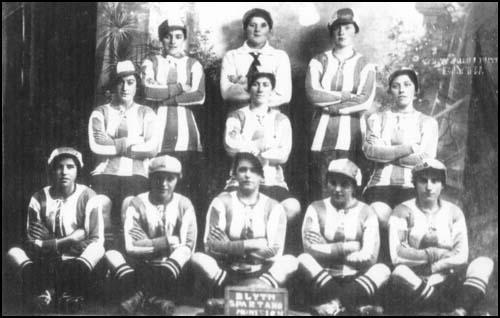

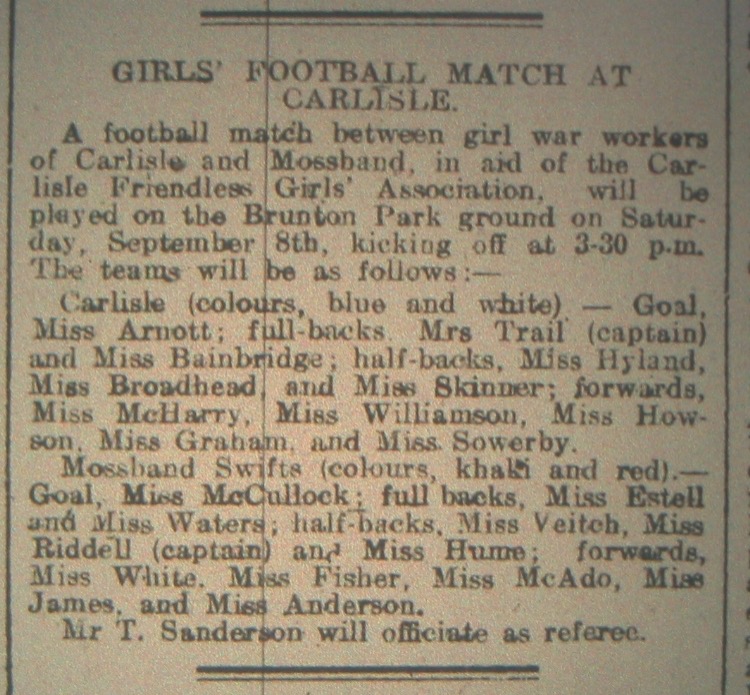

By framing footie as a charitable endeavour, women were able to rebut some of the criticism that surrounding their playing of the game.

By framing footie as a charitable endeavour, women were able to rebut some of the criticism that surrounding their playing of the game.

On Boxing Day of the same year, the two teams met again, this time in aid of the Carlisle Nursing Association. This time the Swifts were less fortunate, and they lost 4 -1.

On Boxing Day of the same year, the two teams met again, this time in aid of the Carlisle Nursing Association. This time the Swifts were less fortunate, and they lost 4 -1.

Peggy Leadbetter, Nellie Hoar and E. Atkinson, process workers, and Ann Atkinson, trolley worker, were charged with being absent from work in April 1917. They didn’t seem to take the tribunal process very seriously, the local newspaper recorded that they

Peggy Leadbetter, Nellie Hoar and E. Atkinson, process workers, and Ann Atkinson, trolley worker, were charged with being absent from work in April 1917. They didn’t seem to take the tribunal process very seriously, the local newspaper recorded that they

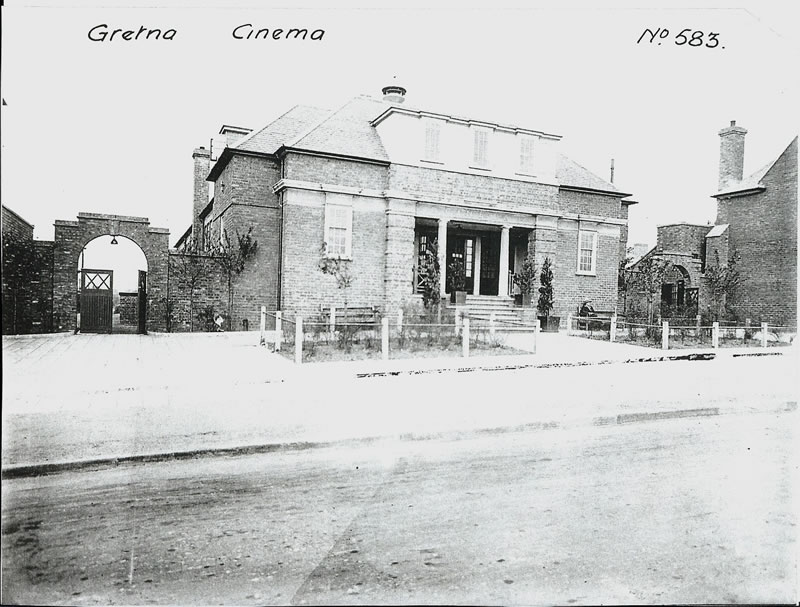

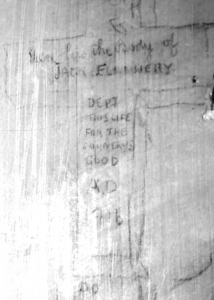

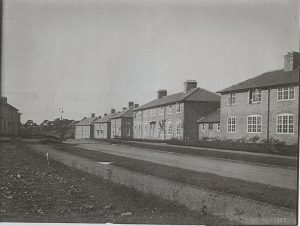

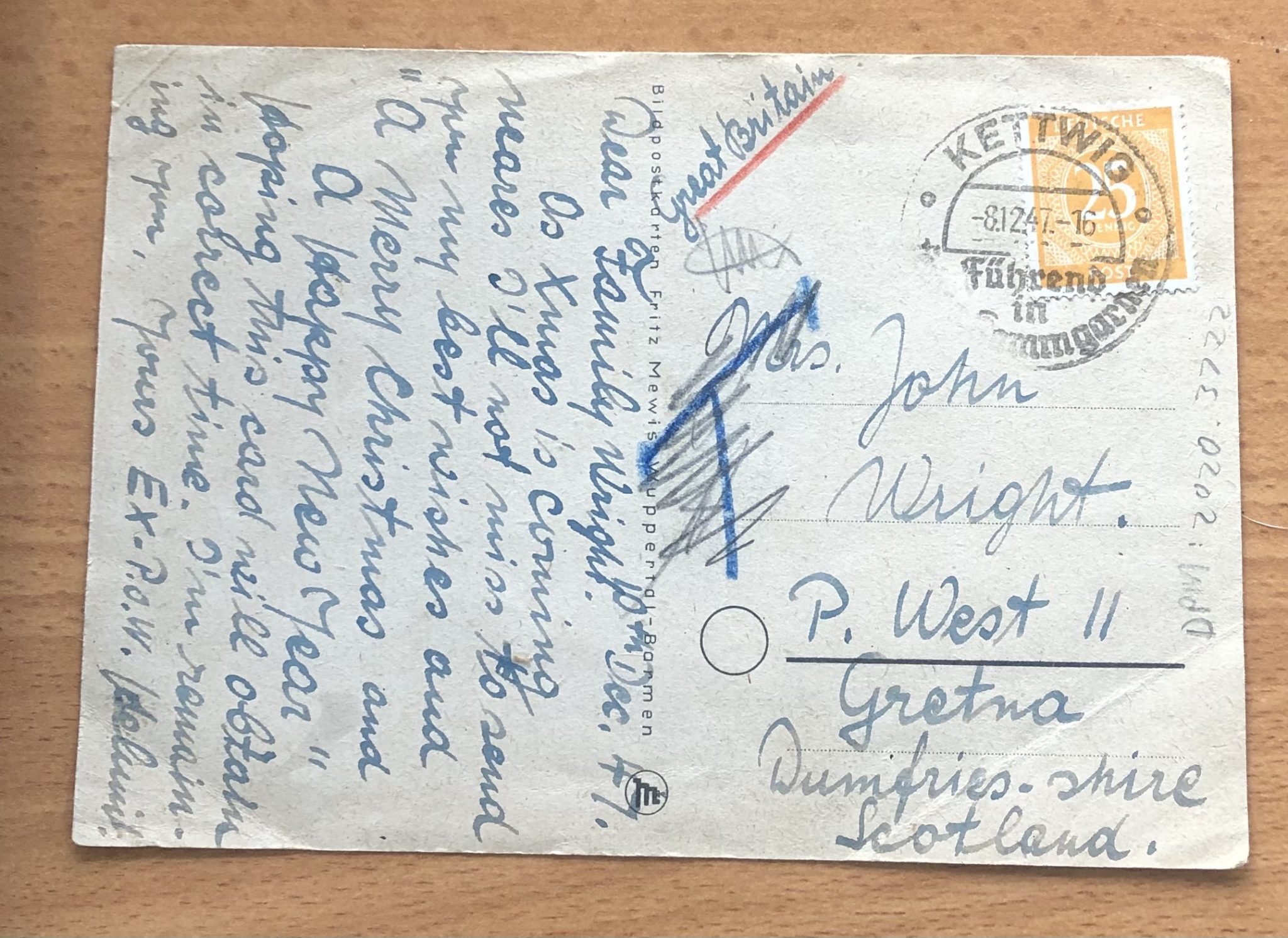

Callum’s house is one of the original World War One houses built to home the 30,000 workers at HM Factory Gretna. This drawing could have been done by one of the builders of the houses (the Factory and townships of Eastriggs and Gretna were built by 10,000, mainly Irish, navvies) or it could have been drawn by one of the workers who stayed in the hostel during the War (12,000 of these workers were women).

Callum’s house is one of the original World War One houses built to home the 30,000 workers at HM Factory Gretna. This drawing could have been done by one of the builders of the houses (the Factory and townships of Eastriggs and Gretna were built by 10,000, mainly Irish, navvies) or it could have been drawn by one of the workers who stayed in the hostel during the War (12,000 of these workers were women).

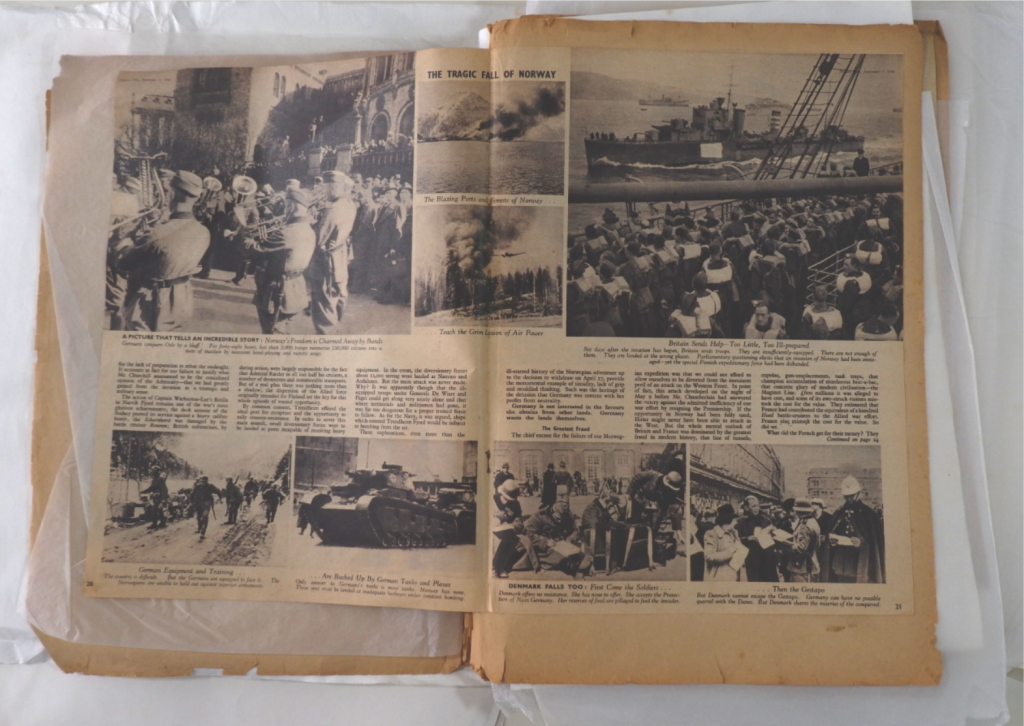

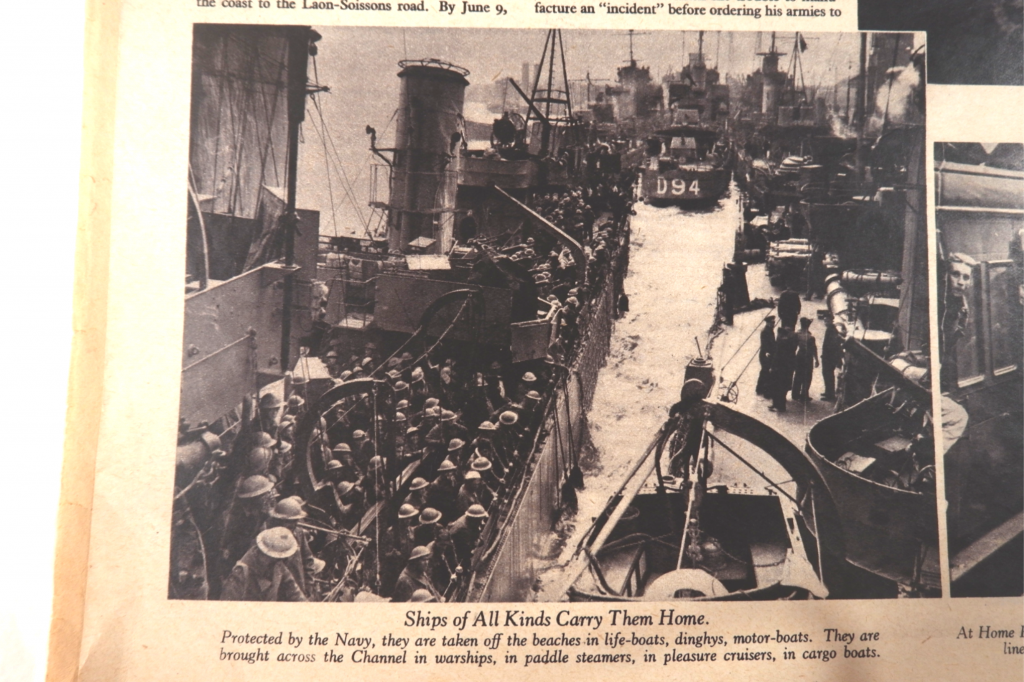

Andy picked the page below and said, “I have chosen this page as it shows a time period of the War when countless people died in the War when Britain attacked Norway in the early stages of War as a strategy to obtain control of the North Sea.”

Andy picked the page below and said, “I have chosen this page as it shows a time period of the War when countless people died in the War when Britain attacked Norway in the early stages of War as a strategy to obtain control of the North Sea.”