A breezy, sunny May Saturday in Middlesbrough. The opposition’s defence is weakening. The centre-forward dashes past players, weaving the ball through legs and passing back and forth with teammates. The back of the net is found. A cheer roars through Ayresome Park. Minutes later, the ball soars into the goal for the striker’s second. The crowd’s celebrations echo round the stadium. Finally, the third goal hits home. A fitting end to the Cup final—a crushing victory over their opponents and a hat-trick for their star player.[1]

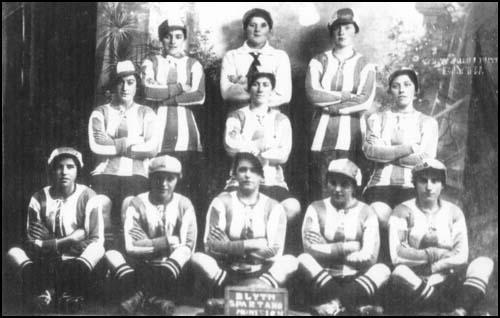

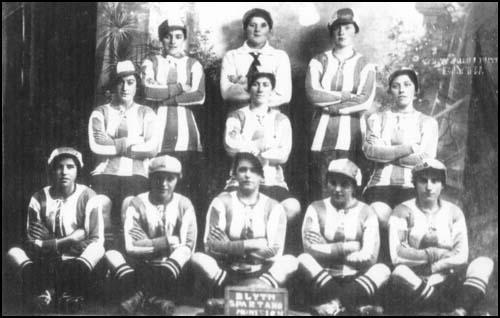

But this wasn’t David Beckham, or Mo Salah, or even Megan Rapinoe. This was Bella Raey, a munitions worker and the daughter of a coal miner. Bella was born in 1900 and during World War One she worked in munitions at the South Docks in Blyth. Between 1917 and 1919, Bella played for Blyth Spartan’s Ladies F. C., a team formed from munitions workers, and England. She scored an incredible 133 goals in one season. In the match I’ve just described, Bella led her team to victory in the Munitionette’s Cup in front of a crowd on 22,000.

But today, Bella is almost completely unknown. This pioneer of women’s football does have a blue plaque commemorating her achievement, but surely we should remember her—and her fellow munitions players—in the same way we idolise Bobby Moore or George Best? This is the forgotten story of women’s football during the Great War, and how the Football Association curtailed women’s football for decades after hostilities ended.

The Beautiful Game in WW1: How Football became Dominated by Women

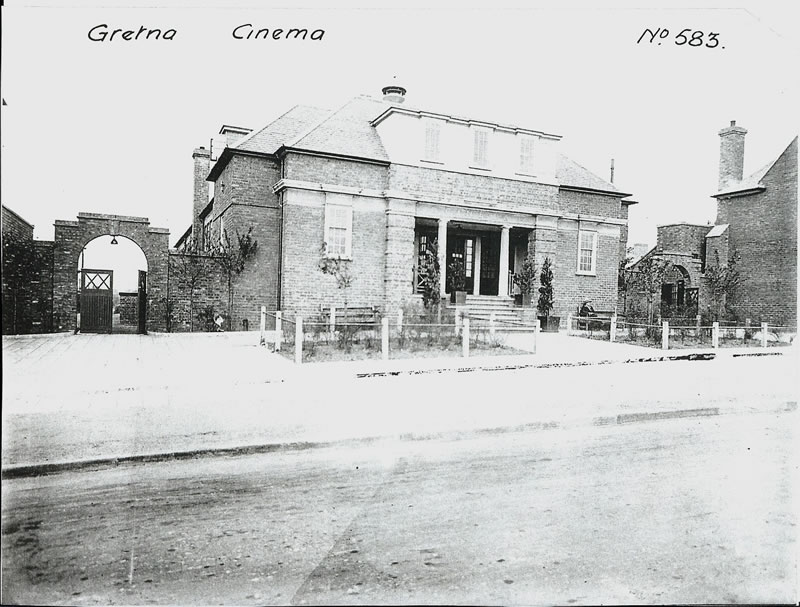

Women’s football had been around long before 1914. In fact, Patrick Brennan has written a fascinating exploration of Victorian women’s football on his blog. But it was during World War One that the beautiful game really took off. Football was a staple part of working-class culture, and war meant that many of its usual players were fighting at the front. This wasn’t the only wartime shift—many women were now a crucial part of the wartime workforce, working in factories, plants and docks, often in areas far from their hometown. This was the case with Her Majesty’s Factory Gretna. Thousands of workers flocked to the Scottish border to work at the factory, and many of these were young, single, women away from their family for the very first time.

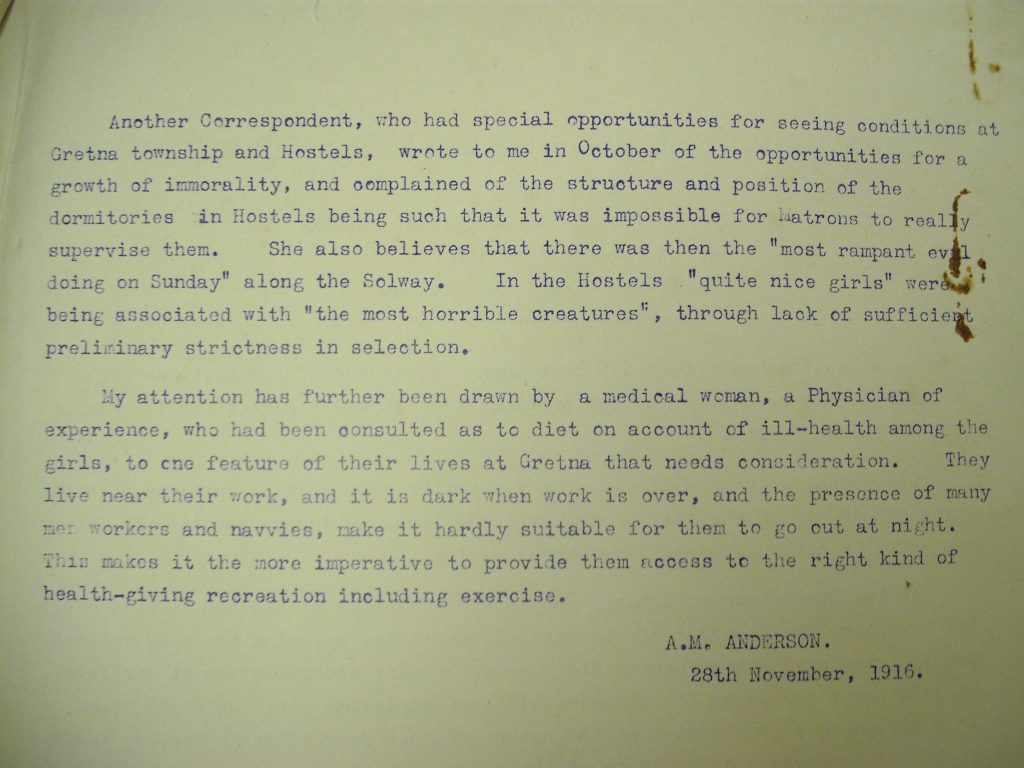

A large gathering of young unsupervised women gave Factory higher-ups and the Ministry of Munitions a moral quandary. The countrywide upheaval of war led to concerns for about the physical and spiritual welfare of factory workers as well as questions about who was responsible for them. Local reverend J.M. Little was vocal in his disapproval of the Gretna girls: ‘there are certain to be not a few of poor morale, of little sense of shame and less sense of honour.’[2]

Because of concerns like these, H.M. Factory Gretna developed an extensive welfare and recreational programme to ensure that its staff were looked after and entertained, but only in ways acceptable to the State.

Sport and activity for Factory workers fell under this recreation umbrella. It was important to the Factory that their employees remained in tip-top condition, because healthy employees were the most productive, and keeping up the rate of production was key to winning the War.

Munitions workers were therefore encouraged to do certain sports. At Gretna, Chris Brader explains in his excellent book, Timbertown Girls, that ‘sports on offer included athletics, boxing, wrestling, tennis, hockey, carpet bowls, cricket and football.’[3] Despite this seemingly encouragement of football at Gretna, it is important to stress that many felt that the game was too rough and masculine for women.

The Blyth Spartans

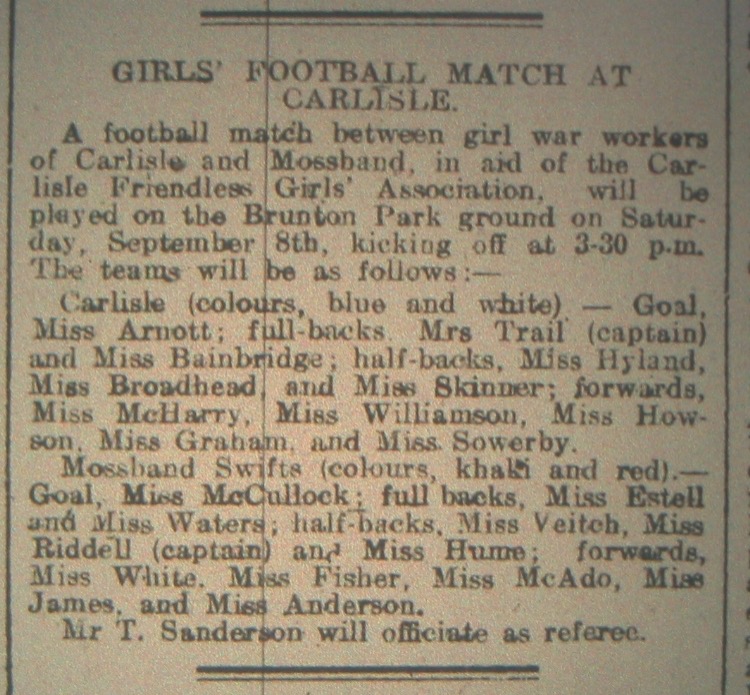

But women wartime workers formed their own, not always officially sanctioned teams. Bella’s team, the Blyth Spartans, were joined by the Carlisle Munitionettes, the Dick, Kerr Ladies Football Club and of course, the Mossband Swifts. These teams, made up mainly of young single women, often played to raise money for charities. On June 1st 1918, the Blyth Spartans and the Carlisle Munition Ladies faced off to raise money for the War Widows’ and Orphans Fund.[4]

By framing footie as a charitable endeavour, women were able to rebut some of the criticism that surrounding their playing of the game.

By framing footie as a charitable endeavour, women were able to rebut some of the criticism that surrounding their playing of the game.

The Mossband Swifts: An Historical Enigma

The Mossband Swifts

We know even less about the Mossband Swifts and women’s football at Gretna then we do about Bella Raey and her Blyth Spartans. Chris Brader’s research revealed that Ernest Taylor, the Social Manager at H.M. Factory Gretna, ‘mentioned that there were ‘one or two’ women’s teams who played on pitches provided by the Recreation Department’, but that these teams weren’t officially sanctioned as they didn’t affiliate to the Social and Athletic Association.[5] In a statement revealing the tensions between Factory management and women’s football, Taylor wrote that ‘there was some division of opinion as to the wisdom on encouraging them to pursue this branch of sport.’[6] Despite this, the Swifts did continue to play football.

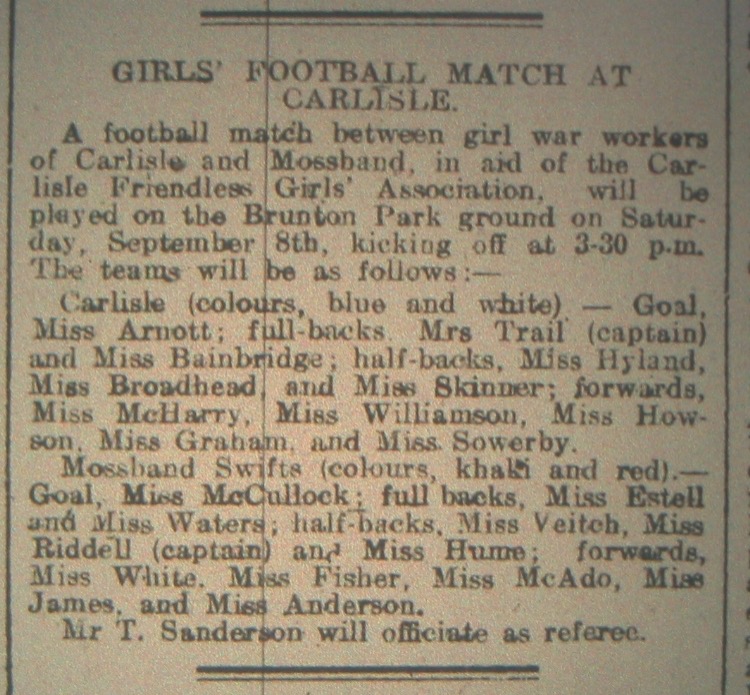

On September 8th 1917, the Mossband Swifts played the Carlisle Munitionettes at Brunton Park in aid of the Friendless Girls Association. The Swifts played in khaki and red and wore shorts, and were captained by Miss A. Riddell. The game ended in a 1-1 draw. The Carlisle Journal stated that ‘there was a large assembly on onlookers despite the rather disagreeable afternoon’ and described the match as ‘perhaps the most entertaining struggle between women that has been witnessed in Carlisle.’[7]

On Boxing Day of the same year, the two teams met again, this time in aid of the Carlisle Nursing Association. This time the Swifts were less fortunate, and they lost 4 -1.[8]

On Boxing Day of the same year, the two teams met again, this time in aid of the Carlisle Nursing Association. This time the Swifts were less fortunate, and they lost 4 -1.[8]

Many questions remain about the Swifts that require further historical research. It would be great if we could identify some of the players and their roles within the Factory. The local papers, the Annandale Observer and the Carlisle Journal are yet to be digitized for this time period—so when archives open, it will be really interesting to see whether the team played any more matches.

The Aftermath of War: What happened to Women’s Football?

In August 1918, World War One came to an end. Soon after, many munitions workers left their factories for the last time and returned home. But this wasn’t quite the end of women’s football teams.

The end actually came in 1921. On December 5th of that year, the English Football Association banned women’s football matches from taking place on Association pitches. Whilst this wasn’t an outright ban of women’s football, it effectively curtailed the sport and made it very difficult for women’s teams to continue. The F.A. gave their reasoning as follows:

‘This august body has decreed that women’s football is undesirable. It is a game “not fitted for females.”…We are not in the least enamoured of women’s football. There have been one or two exhibitions which have not lacked a passing interest as a novelty, but it is to be feared that some, at least among the crowd, went in order to see the women “make exhibitions of themselves.”’[9]

I had to use a Bend it Like Beckham GIF somewhere in this blogpost, and this one fits perfectly!

That wasn’t the end of the sexism though. The F.A. had support. Mr Peter M’William, the manager of Tottenham Hotspur said that ‘the game can only have injurious effects on women.’ Mr A. L. Knighton, manager of Arsenal, argued that if women footballers received injuries ‘their future duties as mothers would be seriously impaired.’ A Mr Eustace Miles stated that ‘the kicking is just too jerky for women.’ Perhaps most surprisingly, the FA even had support from a ‘lady doctor’. Dr Mary Scharllieb, who practised in Harley Street said ‘I consider it a most unsuitable game; too much for a women’s physical frame.’[10] Then this was a push-back on both gender and class terms, by both men and middle-class women.

The F.A’s ban on women’s matches at their grounds didn’t end till 1971. Today women’s football is flourishing, with a record attendance of 77,768 at Wembley during England’s match against Germany in 2019.[11] Now that would make Bella Raey proud.

A massive thank you to Patrick Brennan for sending me some valuable information about the Mossband Swifts.

Sources and Further Reading

[1] See: ‘LOCAL FOOTBALL’ Blyth News, 20 May 1918, p. 3 for a full write up of this match.

[2] Chris Brader, ‘Timbertown Girls: Gretna Female Munitions Workers in World War 1’ (PhD Thesis, the University of Warwick) p. 73. Quoting Cumberland News, July 28 1917.

[3] Chris Brader, Timbertown Girls, (Bookcase, 2014), p. 107.

[4] Blyth News, 30 May 1918, p. 2.

[5] Chris Brader, Timbertown Girls, (Bookcase, 2014), p. 112.

[6] Chris Brader, Timbertown Girls, (Bookcase, 2014), p. 112. Quoting material from: IWM, Women’s Work Collection, Mun 14/10, p. 10.

[7] ‘Women’s Football: Carlisle Munitioners v Mossband Swifts’ Carlisle Journal, 11 September 1917.

[8] ‘Munition Girls’ Match – Carlisle v. Mossband’ Carlisle Journal, 28 December 1917.

[9] ‘Women’s Football, Hull Daily Mail, 6 December 1921, p. 4.

[10] ‘Football for Women Condemned’ Hull Daily Mail, 7 December 1921, p. 2.

[11] https://www.itv.com/news/2019-11-09/england-women-set-attendance-record-of-77-768-at-wembley-during-2-1-defeat-to-germany

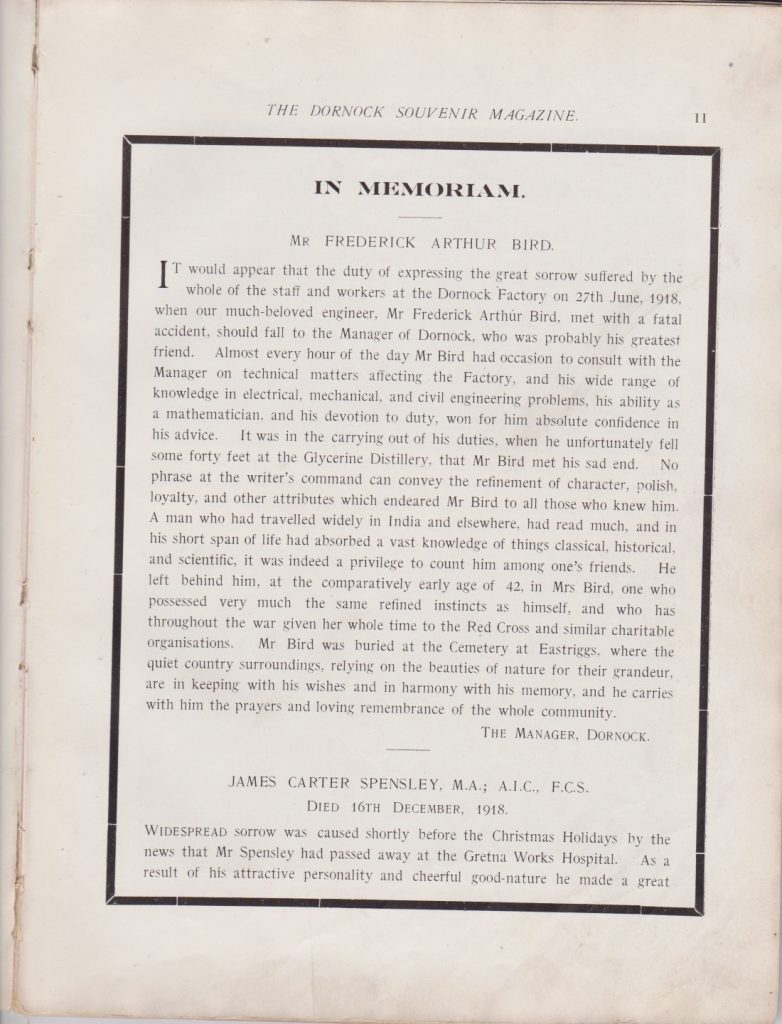

It appears that Frederick was a very popular member of staff at the Factory. In an ‘in memoriam’ written in the Dornock Farewell, a magazine written by staff members and held in The Devil’s Porridge Museum archives, it was stated:

It appears that Frederick was a very popular member of staff at the Factory. In an ‘in memoriam’ written in the Dornock Farewell, a magazine written by staff members and held in The Devil’s Porridge Museum archives, it was stated: This tribute to Frederick was written by none-other than the manager of Dornock, H. B. Fergusson, who describes himself as Frederick’s ‘greatest friend.’ As well as being a hard-working and beloved employee and colleague, Frederick also left behind a family. It’s there that you can really see the human cost of this man’s loss of life. His wife, Ellen died in 1965. She never married again.

This tribute to Frederick was written by none-other than the manager of Dornock, H. B. Fergusson, who describes himself as Frederick’s ‘greatest friend.’ As well as being a hard-working and beloved employee and colleague, Frederick also left behind a family. It’s there that you can really see the human cost of this man’s loss of life. His wife, Ellen died in 1965. She never married again.

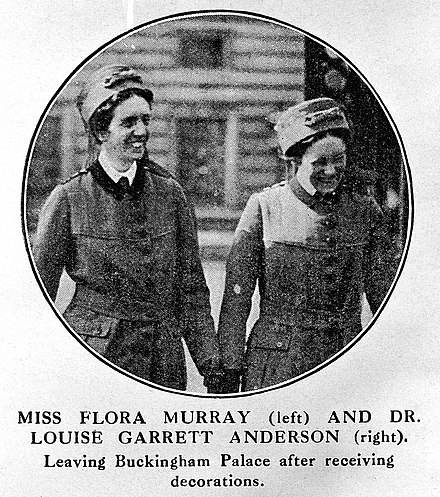

After graduating Flora worked as a medical officer at the Belgrave Hospital for Children before getting a job as an anaesthetist at the Chelsea Hospital for Women. In 1912, she co-founded, with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the Women’s Hospital for Children. The hospital’s purpose was to care for the working-class children of the local community, and its motto was “deeds, not words.”—which might give you a slight clue to the two co-founders’ women’s suffrage leanings.

After graduating Flora worked as a medical officer at the Belgrave Hospital for Children before getting a job as an anaesthetist at the Chelsea Hospital for Women. In 1912, she co-founded, with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the Women’s Hospital for Children. The hospital’s purpose was to care for the working-class children of the local community, and its motto was “deeds, not words.”—which might give you a slight clue to the two co-founders’ women’s suffrage leanings.

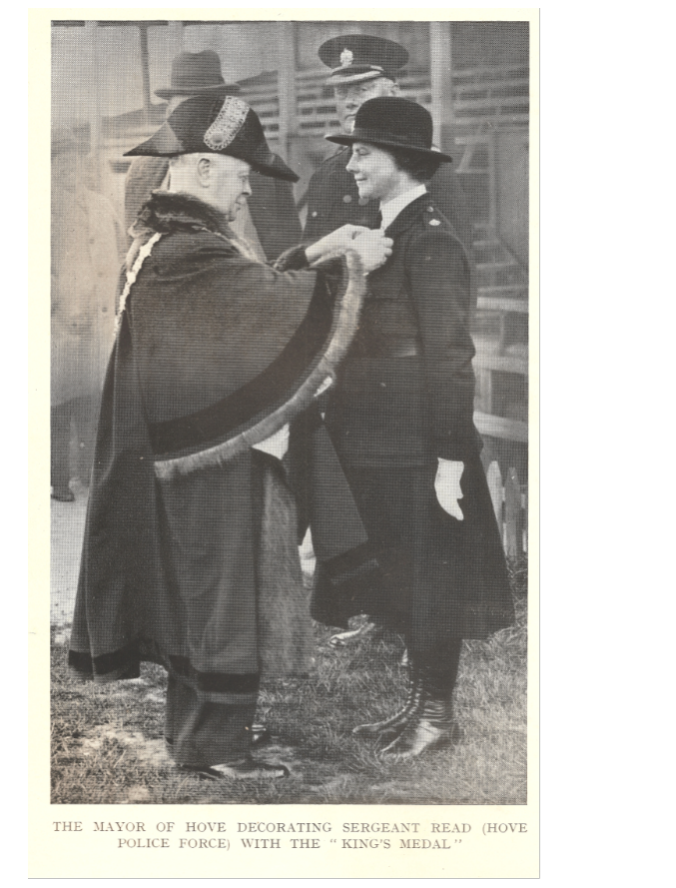

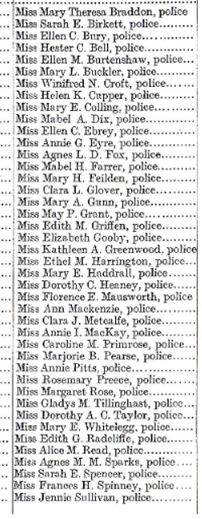

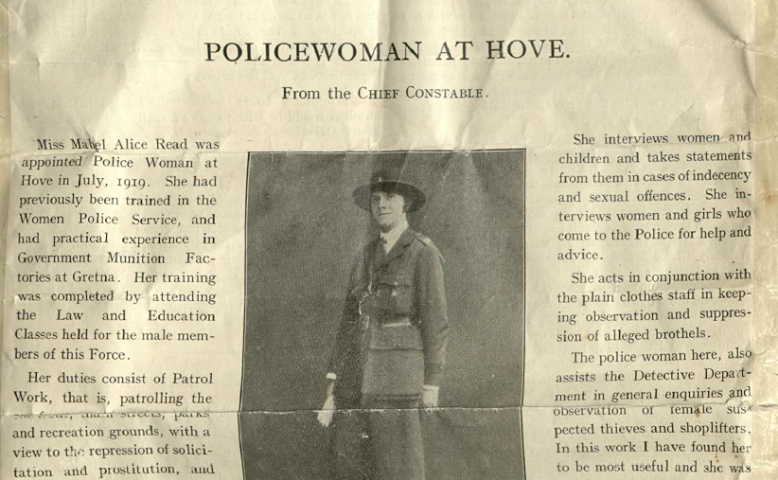

Previously, Mabel’s name appeared on a valuation roll record from Gretna. However, a member of the public reached out to us and shared that Mabel was the focus of an article of the Policewomen’s Review that mentioned, not only her time at Gretna, but also her later work as a policewoman!

Previously, Mabel’s name appeared on a valuation roll record from Gretna. However, a member of the public reached out to us and shared that Mabel was the focus of an article of the Policewomen’s Review that mentioned, not only her time at Gretna, but also her later work as a policewoman!

By framing footie as a charitable endeavour, women were able to rebut some of the criticism that surrounding their playing of the game.

By framing footie as a charitable endeavour, women were able to rebut some of the criticism that surrounding their playing of the game.

On Boxing Day of the same year, the two teams met again, this time in aid of the Carlisle Nursing Association. This time the Swifts were less fortunate, and they lost 4 -1.

On Boxing Day of the same year, the two teams met again, this time in aid of the Carlisle Nursing Association. This time the Swifts were less fortunate, and they lost 4 -1.

Peggy Leadbetter, Nellie Hoar and E. Atkinson, process workers, and Ann Atkinson, trolley worker, were charged with being absent from work in April 1917. They didn’t seem to take the tribunal process very seriously, the local newspaper recorded that they

Peggy Leadbetter, Nellie Hoar and E. Atkinson, process workers, and Ann Atkinson, trolley worker, were charged with being absent from work in April 1917. They didn’t seem to take the tribunal process very seriously, the local newspaper recorded that they