Black History Month is a month-long event that celebrates and commemorates the culture and achievements of Black Britons throughout history. It’s been marked in the UK for over thirty years, and seeks to somewhat address the historical neglect of the vast contributions of the African and Caribbean community to our nation. This blog contains historic use of outdated, offensive and discriminatory language.

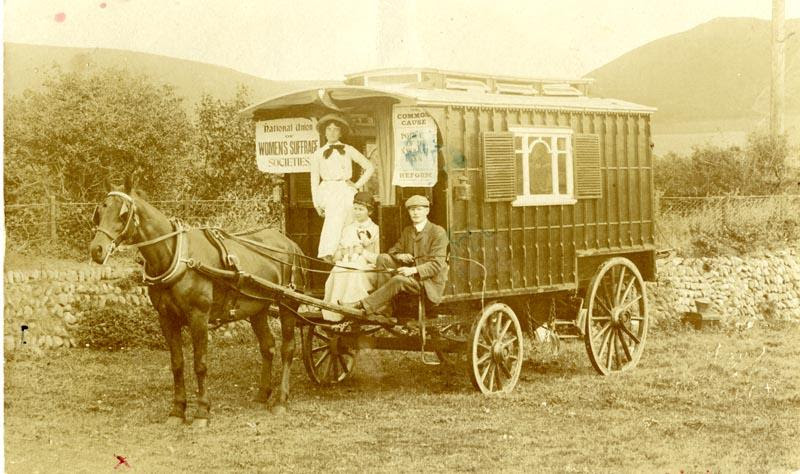

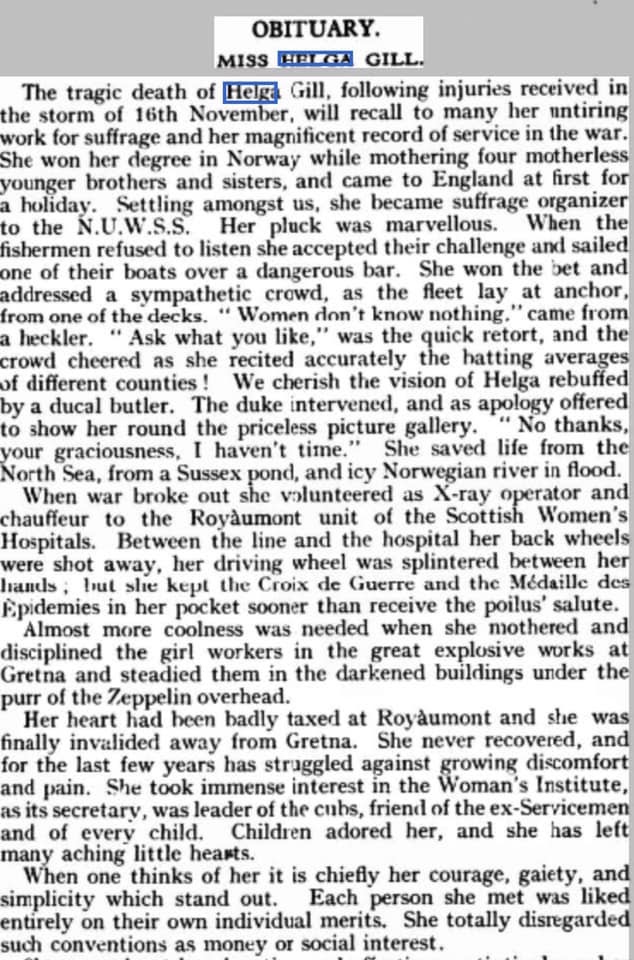

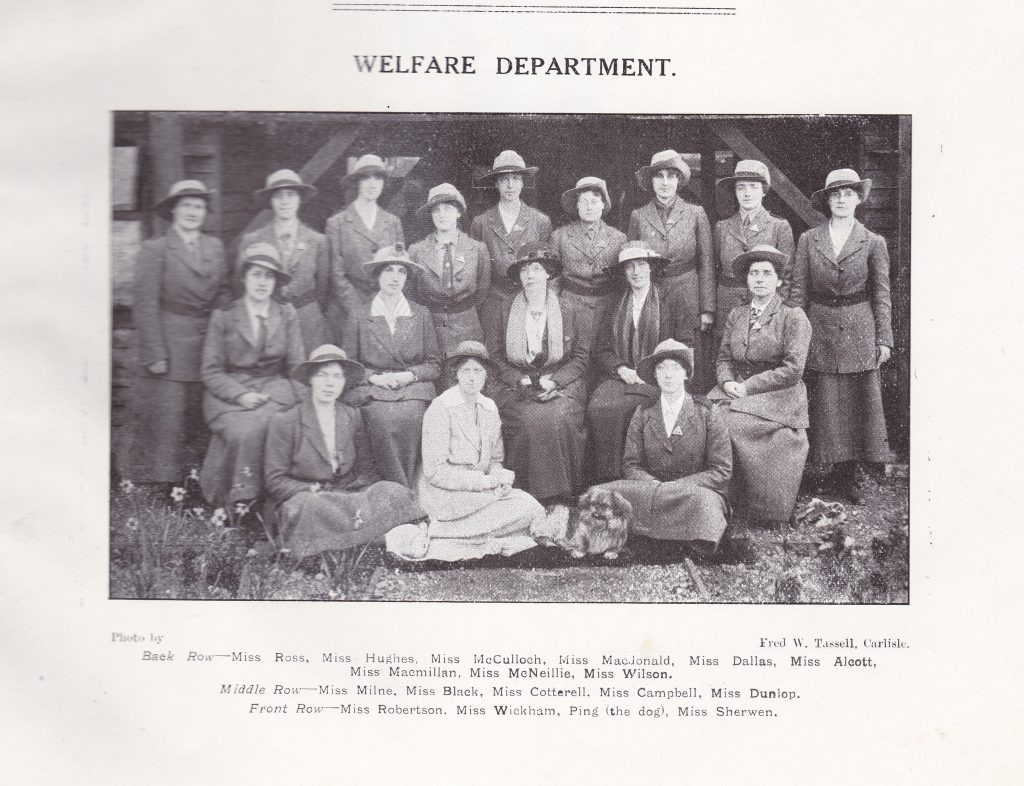

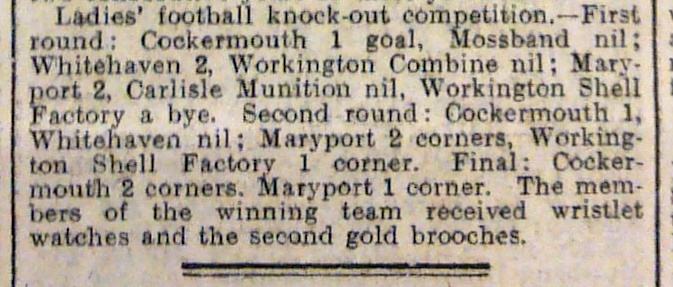

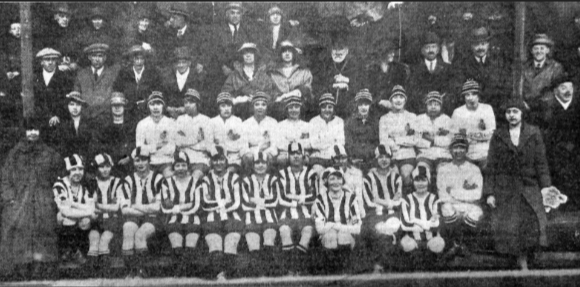

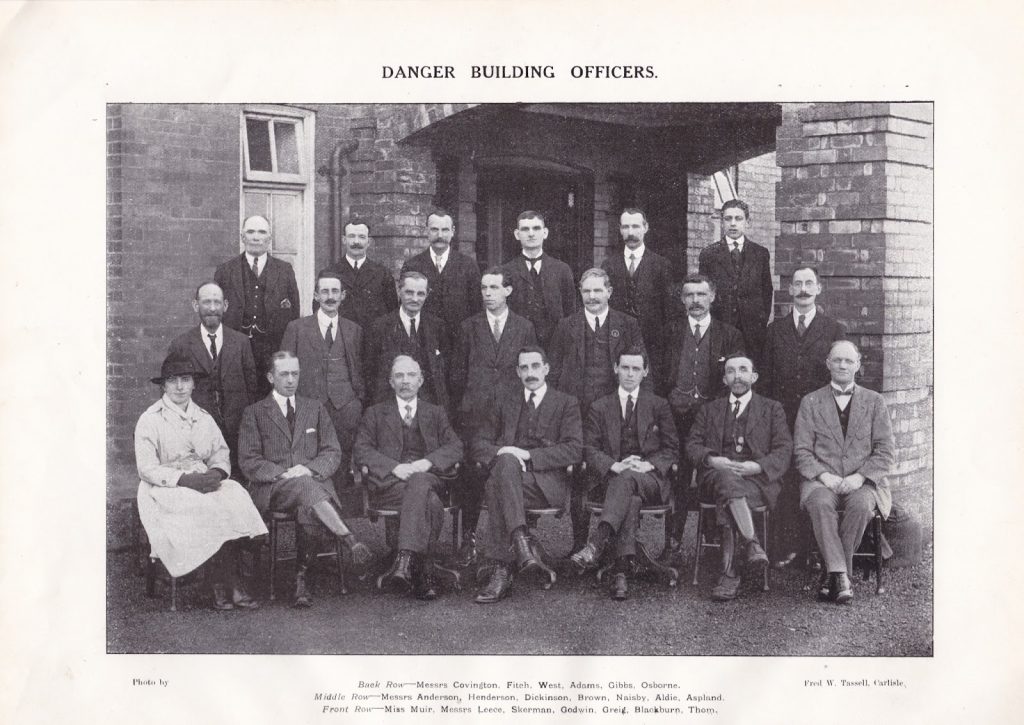

The Devil’s Porridge Museum commemorates the munitions workers of HM Factory Gretna, and the wider contributions of munitions workers across the UK during World War One. Not surprisingly the traditional image we have of the munitions workers is that of “Tommy’s Sister”, a plucky working-class white girl who risked life and limb to make shells and bullets. Whilst the majority of munition girls were young, working-class white women, we also have evidence that women of colour also worked in munitions. Angela Woollacott quotes from the diary of Miss G. M. West, a woman police officer who was working at a cordite factory in Pembrey, Wales. Miss West writes that black women were amongst the workers at the factory.

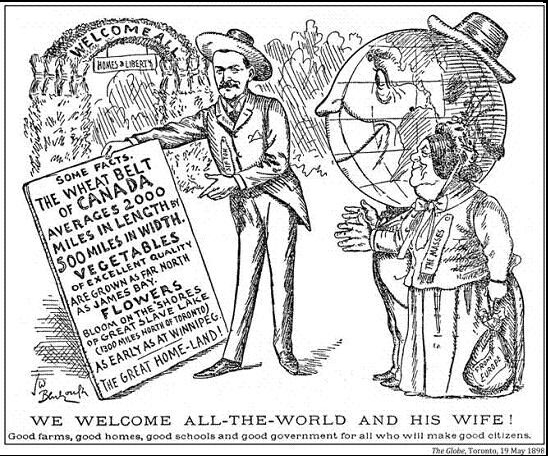

This important aspect of the story of World War One in Britain is woefully unknown, and further research into the story of Black munitions workers is sorely needed. Whilst Miss G M West’s diary relates to a munitions factory in Wales, there were Black Briton’s connected with HM Factory Gretna. Workers at the factory came from near and far, with the majority coming from or living in nearby towns and villages like Dumfries and Carlisle.

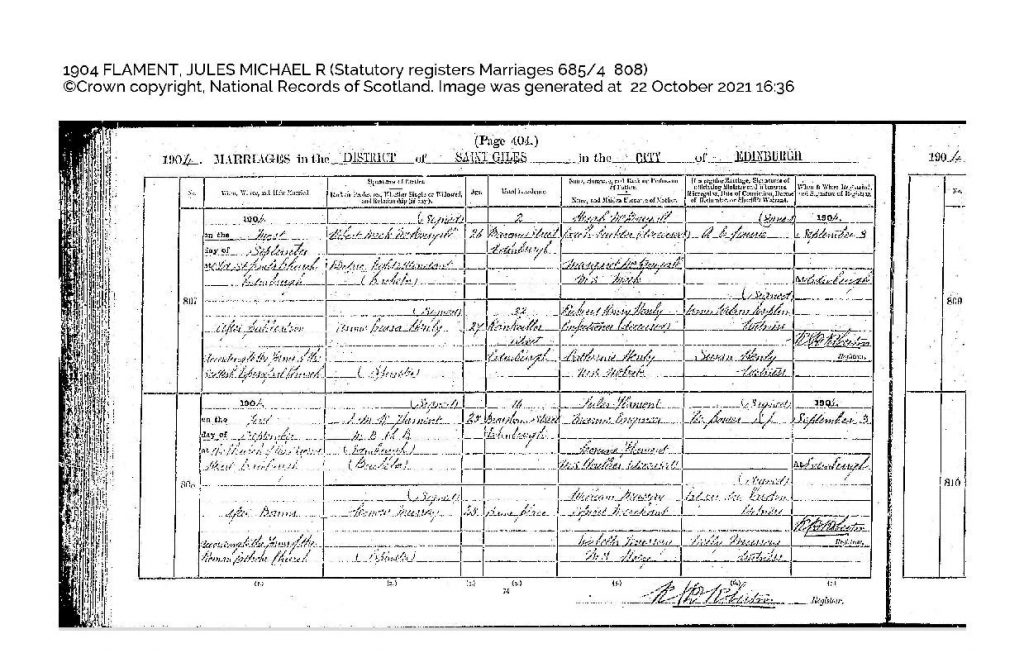

Many of the reports in the local press about Gretna centered on worker’s tribunals, which were set up during the War to resolve complaints and issues facing employees in war industries. These issues usually revolved around alleged thefts, slacking at work, and/or having time off for illness. It was in reading one of these many reports in The Annandale Observer that we came across a mention of Doctor Flament, who had provided a medical certificate for a worker to say that he was suffering from influenza. The attitude of the representative of the firm is racist.

Photo taken of the Annandale Observer, January 1917

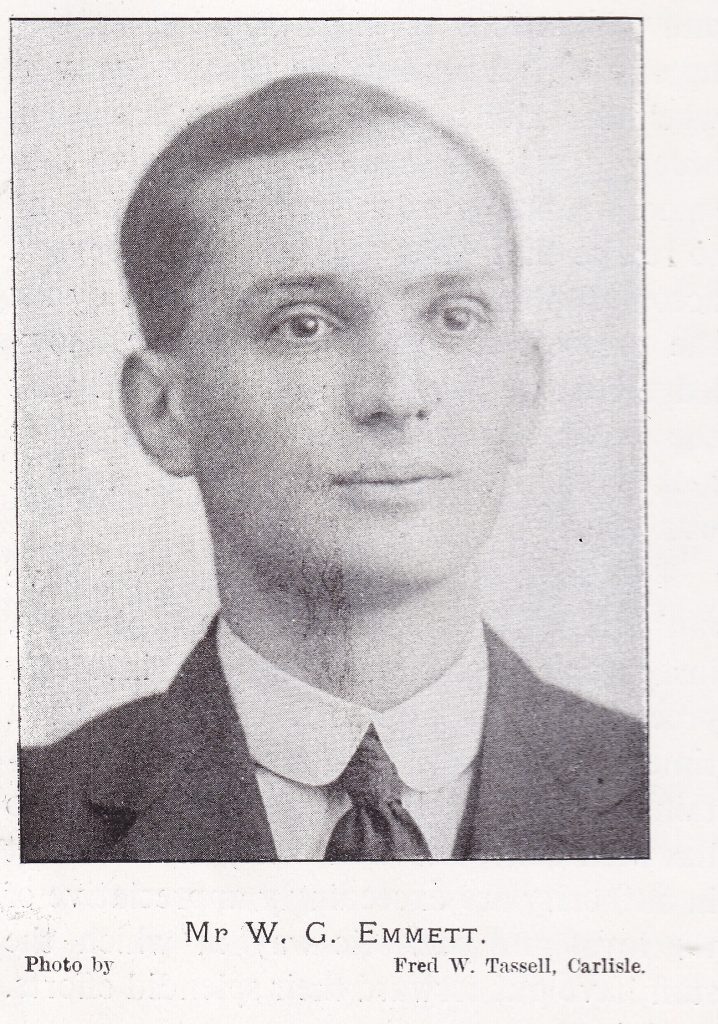

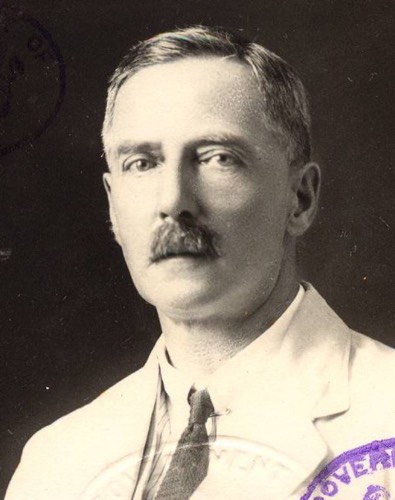

We were intrigued by Doctor Flament. How had he ended up practicing medicine in Carlisle during World War One? What was his experiences of being a Black doctor in this time and area? And where did he end up?

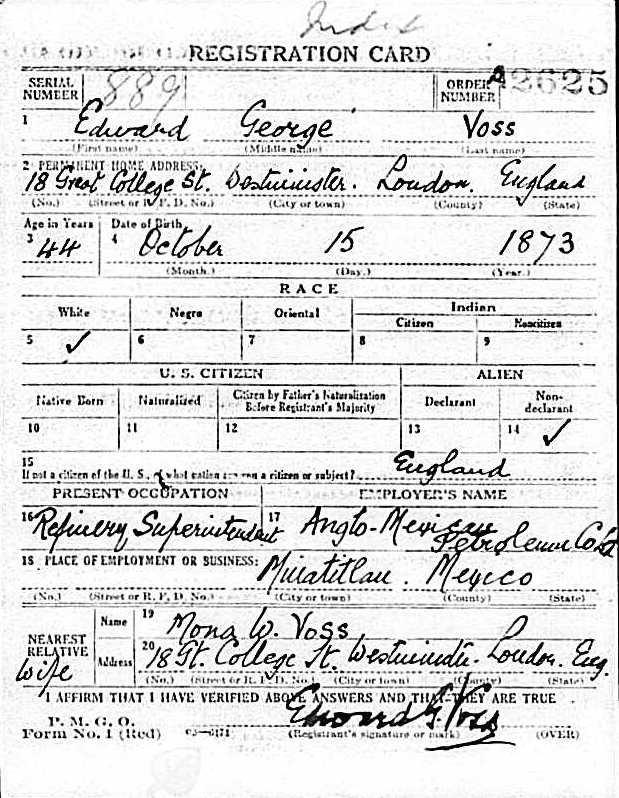

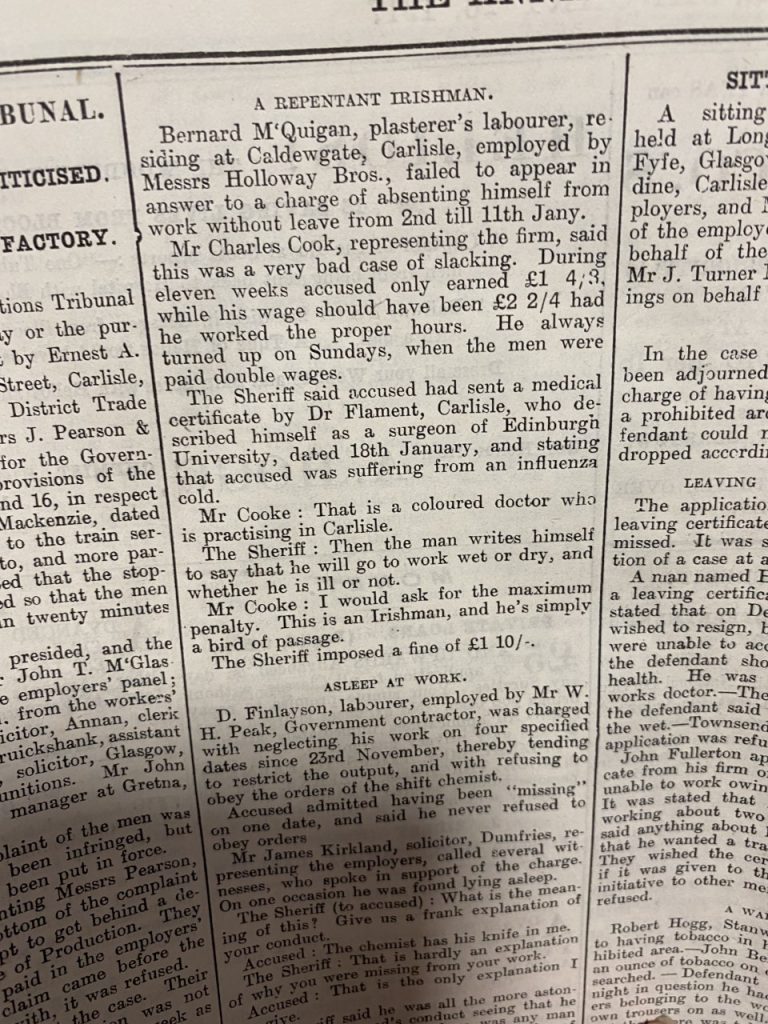

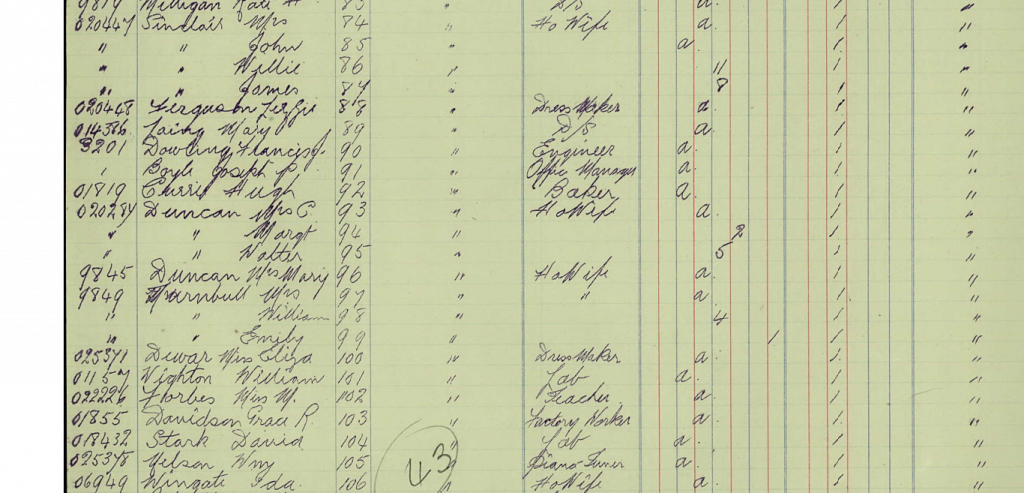

The search to answer these questions brought to light a very interesting man. The first clue to Doctor Flament’s life story, and his full name, was provided in the above article, which stated that he trained at the University of Edinburgh. A quick search of the UK’s medical registers, held by Ancestry, yielded immediate results. A Jules Michael Ralph Flament, who resided at 30 Spencer Street, Carlisle, was on the register in 1907. It stated that he’d graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 1904, with a Bachelor of Medicine and a Bachelor of Surgery.

UK Medical Register of 1907, courtesy of Ancestry

During this time in Britain, Black medical professionals faced rife discrimination. In 1910, Harold Moody graduated top of his class with a degree in medicine. Despite this, he was denied work because of his race, and eventually established his own medical practice. During World War One, Doctor John Alcindor, who (like Flament) had graduated from the University of Edinburgh, was ‘rejected outright by the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1914 because of his ‘colonial origin’’

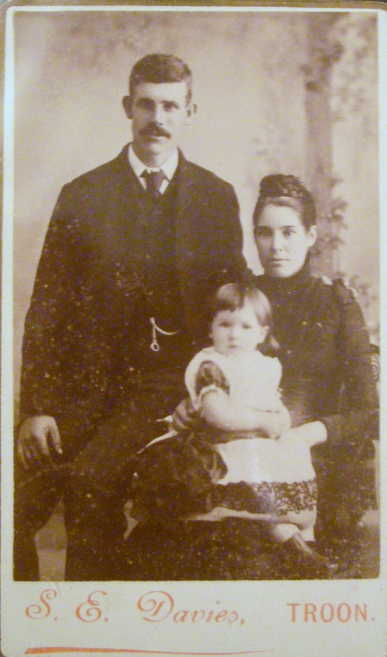

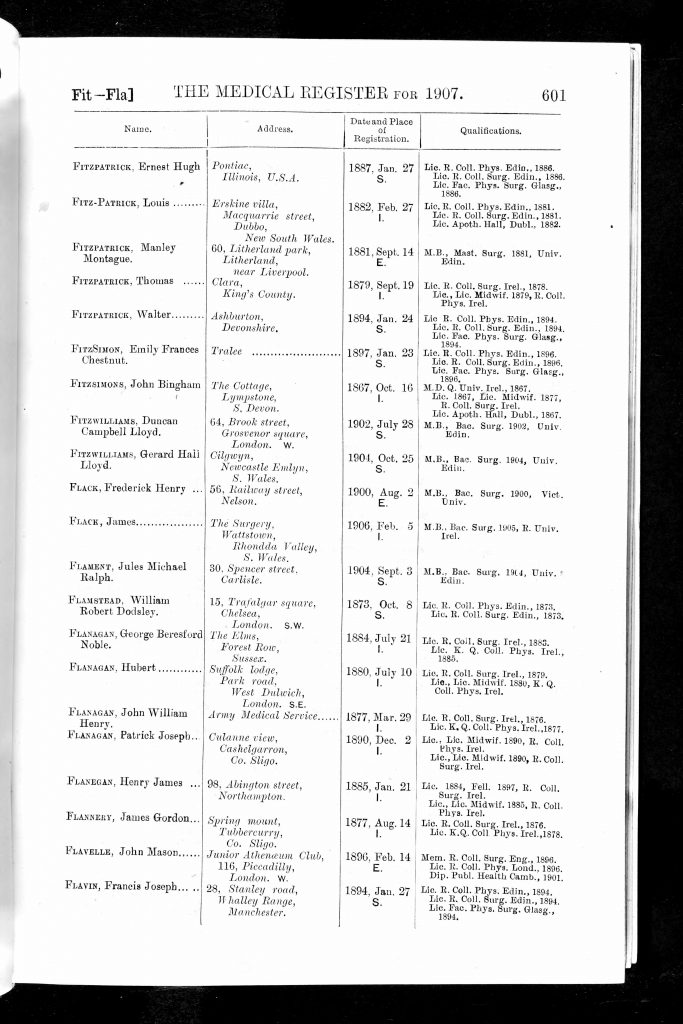

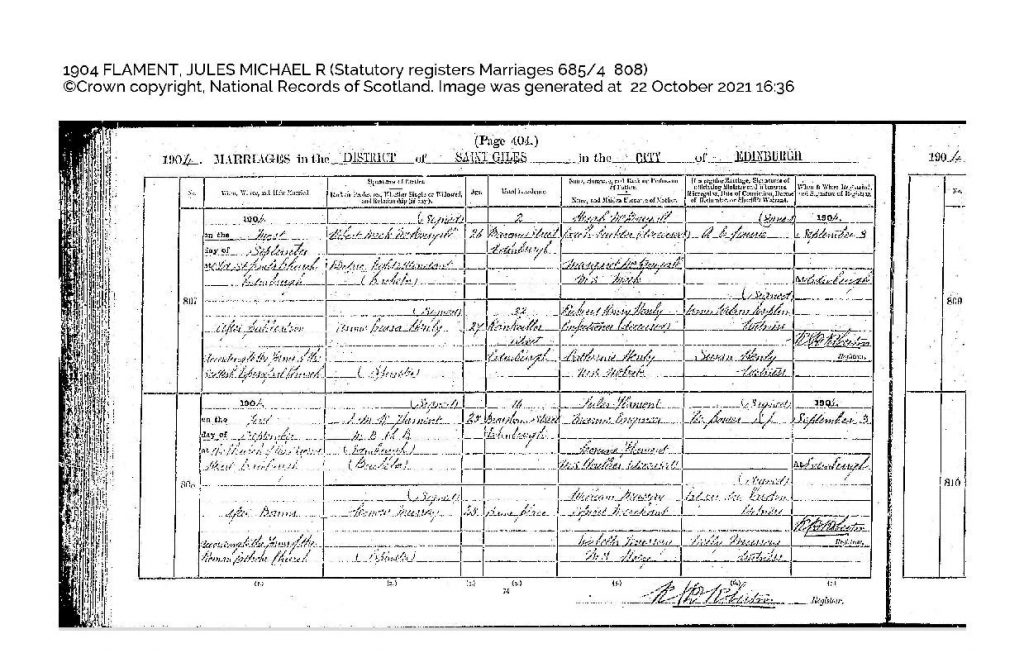

In 1901, Flament was living in Edinburgh, and going by his middle name, Ralph. He was a border in a house belonging to Ann Henderson, a widow living on her own means, and was a surgical student. In 1904, Flament married Leonora Murray in Edinburgh.

The marriage register of Doctor Flament and Leonora Murray

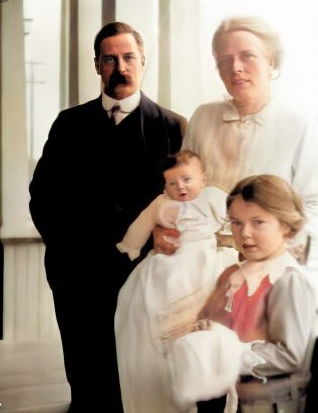

However, shortly after his marriage, he appears to have moved to Carlisle. In 1904, Doctor Flament appeared in the Maryport Advertiser. He dressed the wounds of a lady who had been the victim of an alleged attempted murder. The next year he was the victim of a crime–a man had obtained £1 from him by false pretences. This man, who was named Charles Wm. Seaton, had told Dr Flament that he represented an agency who wished to appoint a medical officer, but the appointee had to take out insurance. In the 1911 census, Doctor Flament is described as 32 years old, married and he was born in ‘The Port of Spain, Trinidad.’ He is also described as being a ‘British subject by birth and parentage.’ He is living with two domestic servants, Annie and Annabella Graham, both 19. His wife, Leonara, isn’t living with him.

In my search for Doctor Flament, I kept coming across oblique references to him being struck off by the British Medical Council, at the instigation of the Ministry of Munitions in 1919, and his name being reinstated in 1931. I couldn’t find out why he’d been struck off though, until I came across a record in the South African Medical Journal:

Doctor Flament was struck off for providing a woman with access to an abortion, decades before it was legal to do so in the UK. The fact that The Ministry of Munitions was a complainant could indicate that the woman to whom this medicine was given was a munitions worker.

I haven’t found any records for Doctor Flament during the 1920s, but it appears that he moved to Mexico. On 17th February 1931, Doctor Flament married Concepción González, and later that year they had a child, Maria. I haven’t been able to pin down what happened to his first wife, Leonora, so it’s possible that they divorced or Doctor Flament was a widower. Doctor Flament died in Mexico on 23rd January 1950. He left effects of £1749 3s 3d. He was working at Doctor Falcon’s Mental Institute at the time of his death.

Doctor Flament’s life and career is important to highlight, because he showcases that Black people are and have always been a crucial part of our collective cultural heritage. However, it is also clear that in the course of his life, Doctor Flament was subject to racism and discrimination. With Remembrance Day fast approaching, when we think of those who worked so hard during the global conflicts of the 20th century it is important to remember and commemorate the Black and Brown people who were soldiers, nurses, munitions workers and in any other job who contributed to the war effort.

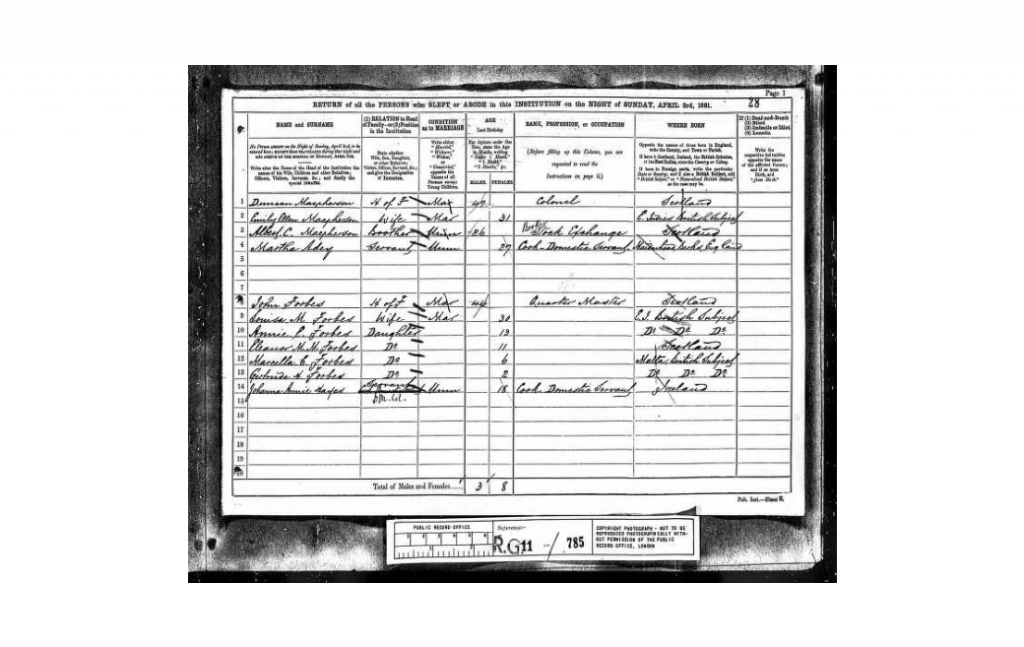

On return from Malta, the 1881 census has the family living at Aldershot Barracks, John’s role is Quartermaster. By 22nd November 1882 they were in Edinburgh when Henry Maurice was born at 21 Scotland Street ( birth registration )

On return from Malta, the 1881 census has the family living at Aldershot Barracks, John’s role is Quartermaster. By 22nd November 1882 they were in Edinburgh when Henry Maurice was born at 21 Scotland Street ( birth registration )