Recently the Museum received a donation of a few items from World War Two to do with the Dig For Victory gardens which was a very successful campaign during the Second World War which involved encouraging citizens to grow their own food to try and combat rationing. The Dig For Victory campaign was very successful and encouraged many people to start growing their own food during wartime.

The Museum has its own garden outside which we have called the ‘Dig For Victory’ Garden which we use to grow some of the vegetables used in our cafe. The Museum uses the Garden through the Summer and will start to plant vegetables in it soon (if the weather clears up).

This is what our Garden looks like during the Summer when in use.

This is what it currently looks like. Hopefully we can start planting things soon!

The items which were donated to us include an informational booklet from the North of England Horticultural Society which included hints about how best to grow some of the plants.

Another one of the items which was donated is also a guide but a slightly shortened down one. This guide is titled ‘War and Your Garden’ and has many tips about growing crops in every different month of the year.

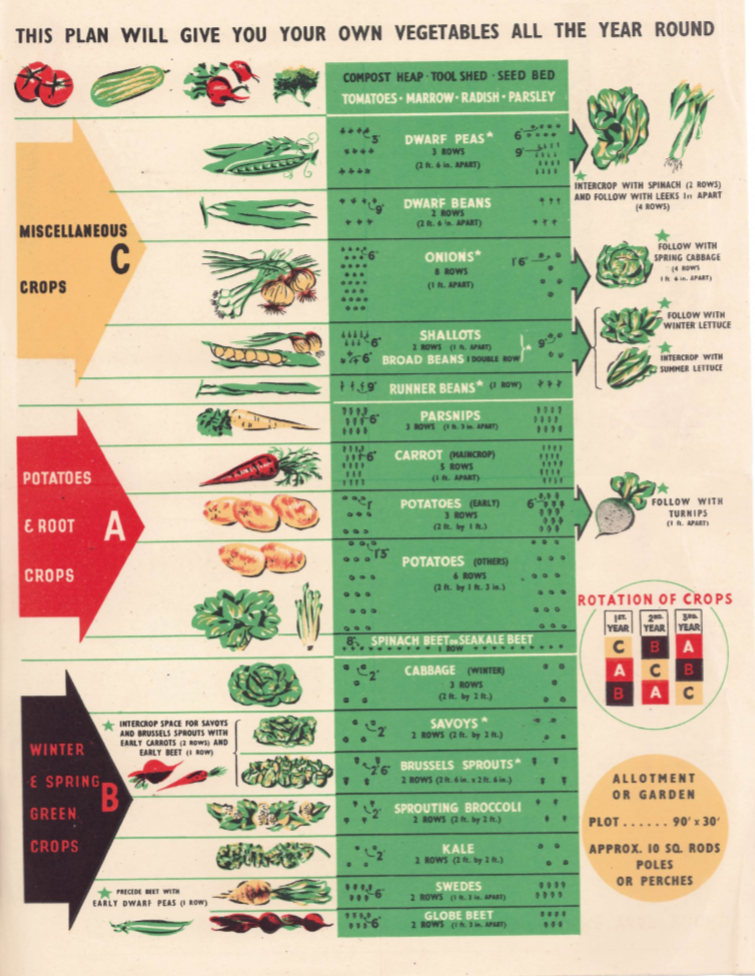

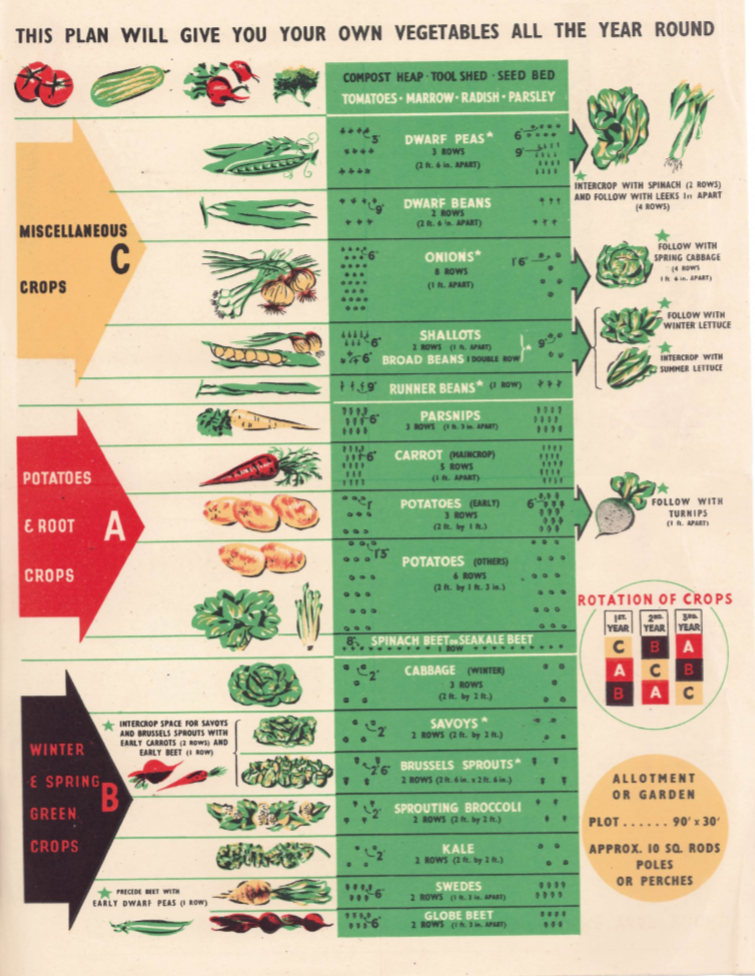

The last item is a plan on how people can grow vegetables all year round and includes information about the best time of year to plant certain crops and also the distance which should be left in between each one when planting.

KBQ’s timeline after the war

KBQ’s timeline after the war